|

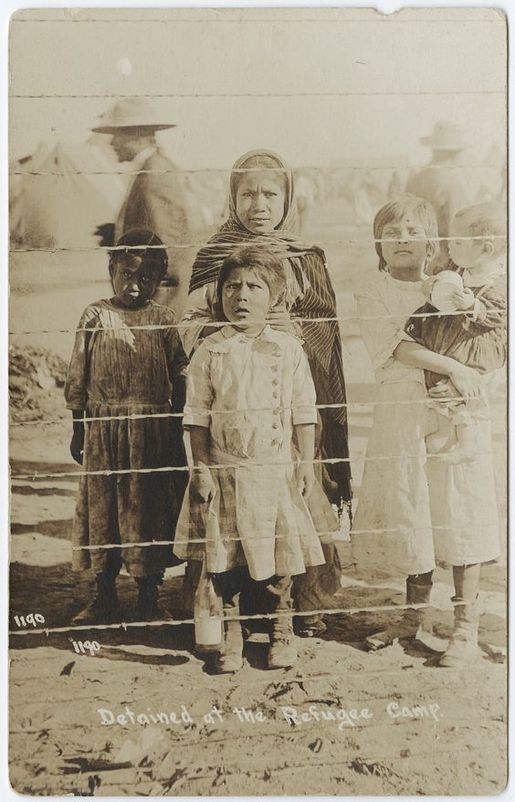

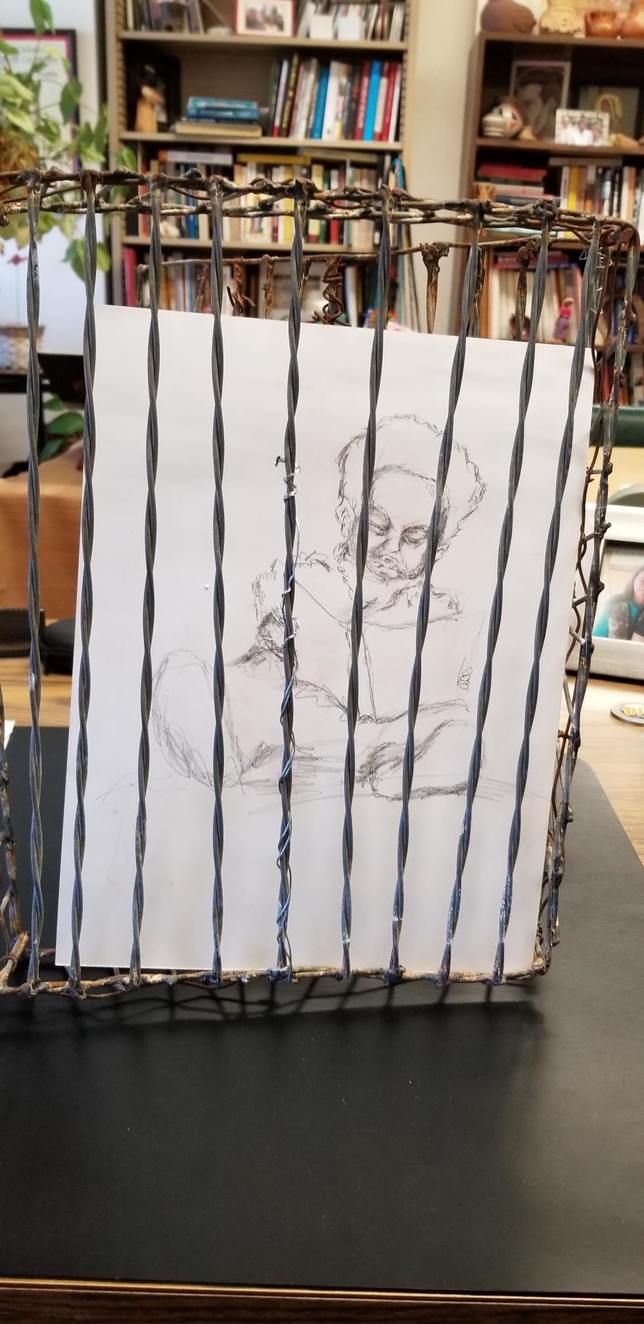

Title: Detained at the Refugee Camp. Creator: Walter H. Horne, 1883 - 1921 Date: ca. 1910 - 1918 Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library. The photographs startled me as I sat in the serene setting of the University of Arizona Library Special Collections that day, 23 years ago. The refugees stared at me from the black and white photographs. Women and men and children stood still for the photographer. Some serious. Some with confusion in their eyes. The children sometimes looking blank and sometimes smiling. There were photos of their preparing food on camp fires. Photos of families and children standing in front of tents or accompanied by soldiers. The captions told me that the location was Fort Bliss in 1914. Following Pancho Villa's victory against federal forces in the Battle of Ojinaga, a battle with over 1,000 casualties, in the winter of 1913, thousands of federal troops and civilians crossed the Rio Grande at Presidio. Throwing themselves at the mercy of the US government, this "steady stream of suffering humanity," as one government official put it, walked four days to Marfa, accompanied by US troops. There they were transported to El Paso via train. Fifty babies were born along the way. According to historian Nicolas Villanueva's The Lynching of Mexicans (University of New Mexico Press, 2017), 5,000 refugees were "corralled behind barbed wire as 'guests' of the United States." Why place refugees behind a barbed wire fence? Villanueva writes that Americans feared that the thousands of refugees would enter the nation and "swell the impoverished neighborhoods in El Paso." He writes that the American press characterized the internment camp as so wonderful that hundreds of El Paso's Mexicans tried to break into camp. There is no evidence of this other than the English language media's propaganda. Historian Ligia Arguilez has uncovered another history-- one of fear, trauma, escape attempts. This is the history that came rushing back when I heard the news that on Tuesday Fort Bliss had been chosen by the Department of Homeland Security to house 12,000 asylum seekers, families. Fort Bliss will house families while Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo has been chosen to house children. This is not the first time in recent history that children have been detained on military bases. In 2016, Fort Bliss housed hundreds of unaccompanied minors. Under the Obama administration, numerous military bases were used to house children crossing the border. A century after the "steady stream of suffering humanity" was corralled behind barbed wire at Fort Bliss, we are witnessing the upcoming internment of possibly 12,000 refugees on the same military base. "How close can I get to you and yet do I really want to get that close?" Art work by Lucia Martinez (2004) On Saturday, July 30, hundreds of thousands of people will march in "Families Belong Together" rallies. In DC, 300,000 are expected to participate. The rallies have been organized in every state of the Union as well as at international locations. It is a strong response to the question posed by Melania Trump in her recent visit to a children's detention center in Texas on June 21. "I don't care. Do u?" Yes, hundreds of thousands of us care enough to rally in public for families and children. As I sat in the offices of the Border Network for Human Rights last night in a room full of people making posters for the upcoming rally, I knew the answer. Here on the border, in El Paso where Fort Bliss engulfs us more and more with each passing decade, we know we have to be vigilant beyond the rally. Growing up less than two miles from Fort Bliss, I thought of it as the place my daddy went to work every day to inspect the clothing and items left behind by soldiers who had left. Today, I know it is the largest Army base with 1.2 million acres that spread from West Texas to Southern New Mexico. It is located in the Chihuahuan Desert. In the summers, it is unbearably hot. 12,000 refugees can easily disappear into this behemoth. Rallies are important-- we've seen the impact that they have. Beyond the rally is just as important. People have asked me how to help, especially if they are far from the border. Keep up with the news. Donate if you can. Spread the word. For more information, check out these orgs. Families Belong Together https://www.familiesbelongtogether.org/ Border Network for Human Rights (El Paso) http://bnhr.org/ Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services https://www.raicestexas.org/ Movimiento Cosecha http://www.lahuelga.com/  This Saturday I will march with my 12 year old grandson and hundreds of thousands of others to tell the federal government that Families Belong Together and not behind barbed wire.

0 Comments

I saw a photo of Maria Jesus once-- she was beautiful like her mother, my great-grandmother. A small girl, slender with long hair and sad eyes, she stood with her mother and sisters. They called her Cachuy. She died in 1931 but her story lived on for decades in my mother's tears. In 1931, part of my family left behind a thriving small business to move to Mexico City in the midst of the Great Depression and the virulent anti-Mexican atmosphere that spread throughout the United States in response to the economic crisis. As a child and even a teenager, I didn't understand why they had moved. When I entered college and learned about the massive deportations and repatriations of Mexican immigrants and their US-born children, I discovered that my family was part of a larger history. This week, I uncovered Cachuy's death certificate. I learned that she died at 10 in the morning on October 10, 1931 of typhoid fever in el Hospital General de la Ciudad de México. She was 14 years old. It was the first documentary evidence I had uncovered of her life, yet I had already begun the work of healing the interrupted story. In 2004, while visiting Mexico City, knowing that she was buried there, a thousand miles from home, I went to the great Catedral and had a mass offered in her name. Then I went to my hotel room in el Hotel Histórico Central, prayed and wrote a poem. Sometimes that's all we can do to heal-- pray, remember, and write. And it is a powerful combination. Today, I share that poem with you. Remembering Cachuy who died so far from home because of economic and political events that she had no say in. This is so that people will remember That you were born in Chihuahua

when the nation was at war with itself That you were the youngest daughter of five That you were the middle child of ten That your eyes were green and your hair light brown That you were the one who smiled That your sisters told you that they loved you the most. This is so that people will remember That you spent your short life migrating From Chihuahua to El Paso to la Ciudad de Mxico That your young life was shaped by Revolution and economic crisis And the day to day wonders Of your mother's tortillas and your baby brother's eyes. This is so that people will remember That your mother died when you were ten That when your father left you He crossed the border to drink himself to death That your sisters cried each night alone Missing your mother's touch... her soft gaze. This is so that people will remember That you were not alone That a million others joined you Pushed out of the land of opportunity by violence and poverty and hope that Somewhere else would be better Some imagining a long lost home Others returning to a land they did not know. This is so that people will remember That your last thoughts were of sitting at the kitchen table Listening to your mother hum softly as she cooked That the pain in your stomach could not drown out the memories Of walking home from school laughing That at the end you let go without fear this is so that people will remember That somewhere in this massive city lay your bones Laid to rest so many decades ago In an unmarked grave in the sacred ground of Tenochtitlan That for seventy years your sisters cried To have left you so far from home. From ATejana in Tenochtitlan Mexico City June 29, 2004 Photo courtesy of ApproveMAS Facebook The headlines caught my attention. The Dallas Morning News declared "Texas board of education approves a Mexican-American studies course (but they won't call it that)." The Texas Tribune's headline stated "Texas education board approves course formerly known as Mexican-American studies." One article asserted that the change came because, as the headline boldly asserted, it was "Too dangerous to be called Mexican-American Studies." After years.... no, after decades of fighting for Mexican American Studies in K-12, advocates and educators found the Texas State Board of Education finally agreeing to a course. At the suggestion of conservative SBOE member David Bradley (R, Beaumont) who said he found "hyphenated Americanism to be divisive," Mexican American was removed from the course title. The new name is now "Ethnic Studies: An Overview of Americans of Mexican Descent." The new name was approved by a majority of the board, nine white Republicans, as well as El Paso's representative Georgina Celia Perez, a Democrat. The other Democrats, — Ruben Cortez (D, Brownsville), Erika Beltran (D, Fort Worth}, and Maria Perez-Diaz (D, Converse)-- argued against the erasure of "Mexican American" in the course title. The name change has been controversial to say the least, especially among those educators who have worked for years for an MAS course. Some school districts in Texas already offer Mexican American Studies. In fact, years ago I guest lectured at an MAS class in El Paso. It's not about allowing school districts to teach MAS. As news articles have reported, the TSBOE class will be modeled after Houston class. What the TSBOE vote does is provide support to school districts state-wide by developing TEKS (Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills) and centralizing the class. It will provide resources to school districts. "So what's the big deal?," people ask. The course was approved. Students will have access to a course they didn't have before. And politics requires pragmatism and negotiation. And a name is just a name. Those are some of the arguments that have been made in support of the name change and TSBOE member Perez. Sounds reasonable. At least on the surface. But names make all the difference. Names can either erase historical connections or they can nurture the consciousness of connection. I had a reminder of that this week. I have a xoloitzcuintle dog, perhaps the most ancient breed in the Americas. Considered sacred by many Indigenous peoples, its image can be found in pre-European contact codices. It is a guide and a healer. It is a national symbol of Mexico. A few days ago, my 12 year old grandson looked at my xolo and said, "You cute Hispanic dog!" I laughed at the characterization but it was a striking example of how labels make a difference. Over almost three decades of teaching Mexican American history, I've witnessed the label "Hispanic" emerge as the normalized and often the preferred label among Mexican Americans. By calling my xolita "Hispanic" my grandson unknowingly erased the deep Indigenous history of my beloved dog. There is nothing "Hispanic" about a xoloitzcuintle. Labels can erase connections. Xoloitzcuintle from Borgia Codex and my xolita. Erasing the "Mexican American" in Mexican American Studies echoes the Arizona attacks on MAS that these courses are "divisive." It's a tired, old trope that's been used by right-wing conservatives across the Southwest.

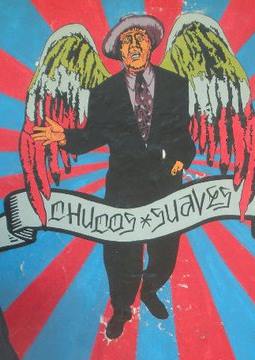

Renaming MAS separates the class from its history and from its academic roots. Would the TSBOE decide to rename political science? Biology? Computer science? As journalist Elaine Ayala writes, "Mexican American Studies is also an established field of study recognized by institutions of higher learning. The academy has accepted the work of fellow scholars of MAS and how they’ve chosen to self-identify that scholarship: the books, research projects and classroom work." If the name doesn't matter, why did Bradley move at the last minute to change the name? MAS was founded because we claimed the right to name ourselves and because we believed our history was worth teaching. What the TSBOE is saying is that they will benevolently allow us to offer a class but we, as scholars, don't have the right to name ourselves or our field. In fact, Bradley told a journalist, “They just can't figure out how to say thank you.” In 2013, "Hispanic" students became the majority of Texas students. Do we need to "thank" the TSBOE for providing relevant education to our youth? Aren't they there to respond to the needs of the students they serve? The TSBOE vote is a tragic but classic example of creating an interruption whose consequences will trickle down through generations. It doesn't have to be that way, however. We have the right to name ourselves. We have the right to respect for our academic scholarship. We won't be erased. For a video of the vote, click here: "Texas Approves Mexican American Studies."  Photo courtesy of Ana Reza. Beauty is a bridge between the past and the future. Recently, I wrote a blog post about Barrio Duranguito, a south side El Paso neighborhood that has been under siege for a year and a half after the City Council voted to demolish it for an arena. We could say it's been under siege for decades, a victim of purposeful disinvestment by its property owners and neglect by the City. The interrupted story of the barrio has been utilized to create an image of the neighborhood as one that is ugly, worthless, and old and its people disposable. The true story of Duranguito has been interrupted by the actions of the City government, the property owners, and sometimes the media. Since voting to demolish Duranguito in October 2016, the City has allowed it to fall into further decay: a drive by demolition in September 2017 caused damage to many buildings. A vacant lot has been allowed to become a dumping place. Homes are boarded up. Gardens, fenced in by the City, are dying. It reminds me of a scene in the 1981 movie Zoot Suit. As the defendants were nearing their trial, they were not allowed to bathe or shave or change clothes. They appeared before the jury looking disheveled and unclean, just what the 1940s White jury imagined Mexican Americans to be: dirty Mexicans. The powerful create the negative image that society expects and then justifies injustice by pointing to the dirty Mexicans or the unsightly barrio as not worth saving. That is part of the interrupted story: we are kept from the true images of Mexican American youth who take meticulous care of their appearance or the beloved barrio where residents paint their apartments, plant geraniums and fruit trees, and sweep the sidewalks in the early mornings. A historic building on the corner of W. Overland and Chihuahua Street following the demolition attempt. Photo courtesy of Paso del Sur. In this scenario, what can we do? The residents and allies of Barrio Duranguito don't have the millions that its enemies have. We don't have access to the political power that its opponents have. But we do have something important: we have our bodies to put to work and we have hope. Those are powerful. In recent weeks, we have been bridging the interrupted story by creating beauty. The vacant lot is slowly being transformed into a garden. Windows are painted beautiful colors. A drab chain link fence is transformed by red plastic cups. Duck tape spells out the words "Viva Duranguito!" Trees are wrapped in colorful yarn and children paint the sidewalks with chalk. A walkway by the once beautiful rooming house, The Mansion, is cleaned of its clutter. We are people from different backgrounds, in ages from elementary school to 90, who are from El Paso and who traveled here from other cities. We are all called together by our vision of what Duranguito truly is: a place of beauty. Creating beauty is our form of resistance against forced uglification and destruction. Photos courtesy of Ana Reza. In her 2013 book Urban Alchemy: Restoring Joy in America's Sorted Out Cities, psychiatrist Dr. Mindy Fullilove outlines the steps to restoring joy in distressed neighborhoods and cities by describing nine elements. Element 3 is "make a mark." She writes, "As urbanists, we make signs to start a new dialogue between people and their spaces. Whether we are noting history or current events, beauty of horror, we are indicating that the space is important. Signs are the beginning of the change we need to make." By creating spots of beauty and art in a barrio under siege, we are making a mark, declaring joyfully "This place is important." In her chapter on "Element 3: Make a Mark," Fullilove writes that "art calls us." We have seen this happen before in barrios under attack. In 2010, we opened Museo Urbano at 500 S. Oregon, in El Segundo Barrio. Working with muralist David Flores, we commissioned a mural to commemorate pachuco culture, whose roots were in that very neighborhood. As he worked on "Chucos Suaves," residents and students found inspiration. Soon, they asked if they, too, could paint murals and with permission of the property owner, they began their work of beautification and resistance. Soon, the tenement courtyard was filled with smaller murals painted by barrio residents, mostly young men, that called people in. I remember once, while sweeping the courtyard on an early Sunday morning, a woman in her 80s who was walking home on her way back from church, asked if she could enter. A striking mural of the United Farmworkers Union eagle had caught her eye. She shared with me the story of a strike she had participated in in the 1950s and pulled out a tattered UFW union membership card that she still carried with her. Art calls us and beauty encourages hope and imagination.  Monet Munoz and Sandra Enriquez on Museo Urbano opening day, standing in front of the UFW eagle mural painted by a resident. Left to right: Detail from "Chucos Suaves" by muralist David Flores; UTEP MEChA students painting their own mural; Visitors from the Boys and Girls Club taking notes on the community-painted murals they are viewing. The interrupted story has the power to hurt us, as individuals, families, neighborhoods, cities, and even nations. To bridge the story is equally powerful. Bit by bit, we are bridging the story of Duranguito by making a mark and affirming that this place and these people are important.

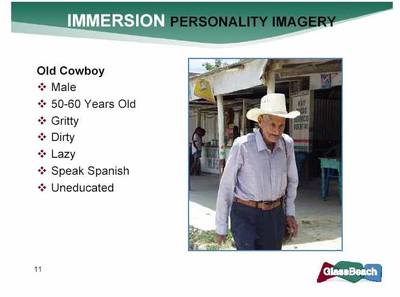

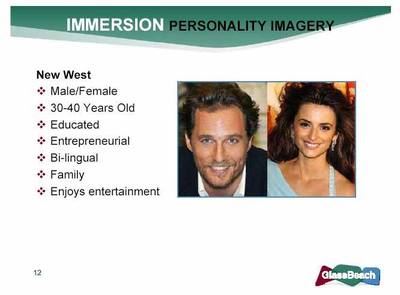

Antonia Morales Fall 2016 UPDATED April 27, 2018 On September 12, 2017, I stood in the early morning coolness with 89-year-old Antonia “Toñita” Morales as we watched a bobcat tearing into the buildings surrounding her home in Duranguito, a barrio on El Paso’s south side. We tried to yell above the horrifyingly violent noise of the machine for the workers to stop; the demolition crew member stared blankly at us as he maneuvered the bobcat back and forth. As it tore into the brick walls, the dust flew around him and bricks thumped to the ground. Workers standing around him mocked us as we yelled that we had an injunction against demolition. It was a surreal moment as I walked around Chihuahua Street surveying the damage, especially the ragged craters left by the bobcat in the corner of each historic home. Unlike other demolitions, the crew had not destroyed any one building entirely. Instead, they had damaged most of the residences and businesses on Chihuahua Street: the old Martinez Grocery, the homes just recently occupied by the Francos who sat outside each evening visiting with neighbors, Don Lupe who tended his beloved garden every year, Olga, and others. As I walked along the street, I thought of the many residents who had been pushed out in the months leading up to that morning, most under duress after months of threats and harassment. One said he was happy to leave but he was a newcomer to that barrio with no particular ties to the place. Fellow Paso del Sur (PDS) member Dr. David Romo and I had walked that barrio many times over the previous year. We had stood on porches and sat in living rooms listening to the histories, the fears, and the dreams of the people who had lived in Duranguito sometimes for decades. Duranguito is more than its architecture. It is the stories of people who made their lives there. Duranguito residents meeting, Fall 2016. How did we get to that horrible October morning event? Eleven months before the demolition attempt, in October 2016, the El Paso City Council voted to demolish El Paso’s first neighborhood in order to build a sports arena that even their own employee testified in court would be utilized perhaps a total of two months of the year. The vote to displace the long-time residents in October 2016 was followed by a reversal in December 2016 to not demolish the neighborhood then followed by a renewed commitment to destroy the tight-knit neighborhood in January 2017. The year and a half of fighting to save their community had taken a toll of people’s health: high blood pressure, depression, and other stress-related illnesses spiked. It has also created a stronger resistance to displacement. Toñita often said that she would fight for her community to the end. Barrios are complex, living beings. They can grow and thrive and they can experience disease. They develop over time as relationships are created and strengthened, both the relationship of the neighborhood to the city and the relationships among the people. When parts of them are destroyed, whether it be the demolition of a building or the dislocation of a resident, it is as we had lost a limb. With the displacement of each resident, the life essence of the barrio begins to decline. The decision to destroy the barrio was much more than simply “economic” and “political,” it was what the municipal government hoped was the final blow in a decades-long campaign of disinvestment, ignoring the code violations of negligent (and wealthy) landlords, and efforts to disappear the history of the place. The City and the developers hoped that by interrupting the true story of Duranguito's rich history and the contributions of generations of its residents, no one would oppose the demolition and displacement. In previous posts, I’ve discussed the ways in which stories are interrupted within individual lives and within families—trauma, shame, forced forgetting, and even not caring. For neighborhoods like Duranguito, the interrupted story is just as insidious because the history has been purposely kept from the people of the neighborhood and the residents of the city. As importantly, the living histories of the barrio, the people themselves, have been characterized and treated as disposable people, without history and without value. The residents of Barrio Duranguito are a vulnerable group. The neighborhood’s average income is $10,000/ year and many survive on monthly Social Security checks of $800. The great majority are renters (who have few rights in Texas) and Spanish is the primary language. The rent averages $350 a month. They are almost all Mexican and Mexican American. Women outnumber men with many older women living alone. The average age is 65. Most have lived in the area for decades. When PDS met with the residents in October 2016, we offered our help. Unanimously, they told us they wanted our help to save their homes. Next, they wanted their landlords to bring the buildings up to code. Although the events of October 2016 were shocking, their roots lay in a revitalization plan adopted by the City ten years earlier in October 2006. Around 1999, a group called the Paso del Norte Group, with a secretive membership made up of the elites of El Paso and our sister city, Ciudad Juárez, formed in order to create an economic plan for both cities. On both sides of the border, low income communities were targeted for displacement in order to bring what developers called “progress” and “revitalization.” In reality, the "revitalization" would enrich their members. Low-income people and almost all El Pasoans were left out of the discussion of how "progress" would be envisioned for our community. Glass Beach Study 2006. On the left: El Paso now. On the right: What El Paso could be. The battle against displacement through the Paso del Norte Group plan has brought an important question to the forefront: who is disposable? In 2006, the City of El Paso paid $100,000 for a branding study conducted by the Glass Beach Firm, which didn’t exist before or after this particular contract, contrasting what El Paso is now and what it could be. There were several images that stood out as we reviewed the study, in particular the one referring to people. The words used to describe El Paso’s current population included “gritty,” “dirty,” “lazy” -- words that had been used against Mexican-origin people since the 1820s when Anglo Americans first came to Texas. It also included the descriptors “Spanish-speaking” and “uneducated.” The last two could describe many of the residents of the south side, including Duranguito—Spanish is the primary language in these barrios and many residents have not had the opportunity to acquire formal education. These two images made it clear who was disposable in our community. Much of the narrative, both in the case of El Segundo Barrio and Duranguito, revolves around history. In attacks against the south side both in 2006 and 2016, the City and their representatives said there was nothing historical in either El Segundo Barrio or Duranguito. Notably, of nine historic districts in El Paso, only one is South of the freeway, south of the railroad tracks. In 2016, the City attorney argued that Duranguito could be demolished because there were no historically designated buildings there. Of course, it was the City’s decision to go against their own 1998 archaeological study that recommended historical designation for Duranguito so it was circular logic. The City decided not to validate Duranguito’s history as significant and then turned around and said they could demolish it because no one had designated it historical. Yet, we know that the neighborhood, which dates back to the 1850s, a neighborhood built on top of an 1827 Mexican land grant, which in turn was built upon the ancestral land of the Manso people, and whose buildings have been deemed architecturally significant by experts, is replete with history. It was not just the architecture that was historic. (And no question that the beautiful architecture is significant.) The living history, the people of the barrio, was important. In 2006, PDS began utilizing the concept of living history to describe the residents of El Paso’s south side barrios. Our history is embodied in the buildings, yes. But our living histories are embodied in the people themselves, the fronterizos whose lives and experiences have created our city. Their lives embody the history of migration, economic development, of Mexican and Mexican American culture, of women’s work, and life en la frontera. As Toñita often says, she doesn’t have to read history; she has lived it. Last fall, our Mayor invited a self-proclaimed historian to talk about the significance of Duranguito. He is known for speaking against south side barrios and dismissing their historical significance in support of City-backed demolition plans. The mayor allowed him to speak for over 11 minutes in a vitriolic rant against Duranguito. (The last time I spoke before the Mayor and City Council about Duranguito, I was allowed one minute.) He reassured the Mayor and Council that Duranguito was not worth saving, that the historians of Paso del Sur had everything wrong and that we were, in fact, chupacabra historians. Chupacabras, you might know, are mythical creatures who suck the blood out of livestock. The mayor laughed with glee at that city council meeting as he proclaimed “Historian throw down!” On May 1, the El Paso City Council plans to appoint him to the Historic Landmark Commission. While it was a ridiculous scene, there was an underlying acknowledgement that history is powerful. The women of Duranguito visiting with each other before their displacement. How do we bridge the interrupted story of a neighborhood? For Paso del Sur, we started with the people. We listened as they spoke and shared their stories of raising families, of migrating to the United States, of working for decades to contribute to the economic growth of our city. We listened deeply to understand how they saw themselves as historical actors. We listened deeply to what they loved about their space. Listen to an example here. And we researched the deep history of the place. Dr. David Romo has conducted meticulous research on Duranguito and generously shared it on our Facebook page. You can find it here. Two particularly beautifully researched and written examples are here ("The Forgotten Lessons of the Ponce de León Settlement Acequias") and here ("Doña Benancia: The Woman Behind the Gold-Digging Men"). Interrupting the historical story can create disease and demoralize people. Bridging the story can plant the seeds of dignity and healing. Photos courtesy of Paso del Sur (Facebook page: PasodelSurEP)

I’m totally deaf in my right ear. It happened as a result of numerous tumors that grew inside my right ear over the course of years, destroying the small bones that allow us to hear. My otolaryngologist told me that the roots of my tumors and subsequent deafness must have started before I was 9 years old. Medicine people have often asked me, “What don’t you want to hear.” “What didn’t you want to hear as a child?” Honestly, I hate that question. I think most of us have things we don’t want to hear and for me, that question elicits fear and anxiety. Not wanting to hear resulted in one of my most significant interrupted stories dragging out until my sixties. So, this is a cautionary tale and a story of hope. My parents told me that I was adopted just as I was about to enter first grade, at the recommendation of my elementary school principal. I didn’t really understand what it meant but as I grew up, I began to hear stories about my birth mother. For most of my adolescence and teenagerhood, I felt numb and disinterested when I thought about her. When I gave birth to my son when I was 25, my anger came out. How could a mother leave her child? As a new mother, I couldn’t imagine. It took many years to heal my relationship with my birth mother, complicated by the fact that she died when I was 21 years old. Somehow, my birth father escaped my attention and my anger. I occasionally heard comments about him. “Dicen que tu papá era americano,” was the most common and the one that made me angriest. How could I have a White father? I was born in Juárez and I identified strongly as a mexicana, and later a Chicana. Looking back, I remember the times that my “authenticity” as a mexicana was questioned and the pain that this caused me. My aunt used to tell my mother that I was too agringada. Once, a stranger I met at a neighborhood tiendita argued with me about my identity, saying that I didn’t have the “face” of a Mexican. Being raised by a very white-skinned mother (to whom I was biologically related) allowed me not to question my own light skin or my features. Years passed. I learned more about my mother, especially when I met my birth aunt, her sister, around 2001. The day I met her in her long-time home in Arizona, she handed me a framed photo of my mother and a manila envelope with several photos in it. “Este es tu papá, she said. “This is your father. He loved your mother very much.” When I looked carefully at them, weeks after she’d given me the envelope, I noticed there were three men, not one. Two were very handsome Mexican-looking men. One had written a very romantic dedication to my mother, calling her “mi reina.” The third was a very young White man, a teenager probably. Could the young white man be my father? Could he be the “americano” that I had heard about in my youth? I laughed and put them away in a drawer where they stayed for years. I chose to believe that none of them were my father. Then about four years ago, I decided to do my DNA. I spit in the tube and sent it off to the lab not because I was thinking about who my father might be but because I wanted to know how Indigenous I was, what percent Native American my DNA was. After finally finding my spiritual community among Mexicans and Chicano people who returned to our roots in Mexico, I needed affirmation. I certainly understand how problematic this is…. But I felt I needed this. Some of my friends in academia make fun of DNA tests and it’s especially easy to do so if you look at DNA company commercials. One of my favorites features Kyle who thought he was German but turned out to be Scottish! Of course, and this is common sense, identity is much more complex than taking a DNA test and we can’t simply switch from lederhosen to a kilt, but DNA is an incredibly useful tool in bridging our interrupted stories. It helps answer questions for adopted people from “What ethnicity am I?” to “Who are my parents?” I remember the day my DNA results came in. I excitedly opened the link in the email. I was 2/3 European, with Irish being predominant. I sat there staring at the computer screen confused. European? Irish? Because I couldn’t believe it, I took another DNA test at another company. Two months later, the new results came in. They were more or less the same: Native American, Iberian, and Irish in roughly the same percentages but the European DNA was again roughly 2/3. I thought of all the ways the Irish had come to Mexico: during the US-Mexico War of 1846-48 with the famous San Patricios and with Irish migration to Mexico during to purchase mines during the Porfiriato. I knew that Chihuahua had the highest numbers of Irish migrants than any other state except for el Distrito Federal. I was trying to make sense of it, but I wasn’t listening. “Dicen que tu papá era americano.” Eventually, as a learned to navigate the DNA websites, I looked at my DNA relatives, those individuals who had also taken the DNA test and to whom I was related to biologically. The list was filled with people whose roots went back to Harlan County, Kentucky. What??? Early in the first couple of years, I wrote to relatives asking if they knew anything about a relative having lived in El Paso, on the border, but no one knew. Of course, I didn’t even know my father’s name. I could see that I was related to families with classic Kentucky last names: Brock, Lewis, Sizemore, Osborne, and Saylor. I was even related to the Fugates, the famous “blue” people of Kentucky who have a gene that produces blue skin of various hues. I studied Kentucky history and learned about the tri-racial Melungeons. I learned about the Cherokee who many of my relatives claim as their ancestors. I learned about the labor strikes in Harlan. Like a good historian, I attempted to put my DNA into historical context. I listened to blue grass music. I looked at photos of Appalachian families. I tried to feel connected. My DNA “family” were overwhelmingly kind. They spoke to their grandmothers and other elders in their families. They encouraged me that I would find out what I was looking for. Just recently, a DNA cousin from Kentucky wrote to me and said, “Welcome to the family.” Their kindness was very comforting yet, I was still confused and more lost than ever. This is a common Internet image of the Blue People of Kentucky. I don't yet have its source. About a year ago, a “new” DNA relative appeared and we were closely related. So closely related that, finally, I learned who my birth father was: an americano from Kentucky. My cousin Melinda Gould put her expertise in genealogy and DNA to work to make the genetic and genealogical connections. My birth father was a young man named Charles who had been stationed in El Paso in the 1950s but whose ancestors had lived in Kentucky for generations. For decades, I had refused to listen. By the time I could listen, everyone who knew anything in my maternal family about my paternal side were gone. Were it not for DNA testing, I may have never been forced to listen. I would not have begun to bridge the interrupted story of my birth father. I would not have found Charles. As I looked through the historical records, I found Charles listed as a small child living in a Harlan County mining town in 1940. The towns were known for their poverty and inadequate living conditions. Coal mining was one of the most dangerous occupations and working conditions were deplorable. It is no wonder that that in the 1930s, the mining camps were “Bloody Harlan,” where miners and unions clashed with mine owners and law enforcement. In a 1931 article, John Dos Passos wrote about the impoverished conditions of coal miners. One coalminer’s wife testified that her family of four barely managed to exist. My father’s family had not always lived in the mines. As I went back from census to census, tracing his father and mother, then his grandfather and grandmother, they were farmers. Earlier generations farmed in Laurel (home of Kentucky Fried Chicken) and Perry (think the “Dukes of Hazard”) going back to the early 19th century. Earlier, the family moved across N. and S. Carolina, eventually settling in Kentucky. In Alessandro Portelli’s They Say in Harlan County: An Oral History, one of the narrators says that sometimes, out of desperation, farmers came to mining camps to look for work, without a clue as to what mining entailed. “But they were glad to make a little money even under those conditions….” Said one narrator. Charles died about twenty years ago. I’ve tried to discretely contact his family—they have not responded. But it’s fine. I have the bridge I needed to heal the interrupted story. Finally, fifty years later I listened to what I didn’t want to know and I found my heart growing to welcome in all the new ancestors that I found. A grainy 1924 photo of Felicitas from her local border crossing card. The story of Felicitas Leyva is one of the interrupted stories that wove itself throughout my childhood and remained with me into adulthood. I’ve never stopped thinking about her and, as the years have passed, I have felt a strong imperative to bridge the story of Felicitas and her husband, John Lucas. Training as a border historian has assisted me in this journey of recovery. As I’ve written previously, stories may be silenced, forgotten, hidden or apparently lost but they are simply interrupted, not destroyed. Their presence continues in our lives: in the way we view the world, in the way we look physically, in all the aspects that make us whole human beings. My father related fragments of the story of his tía Felicitas. He was a boy when she came to El Paso. He said his aunt moved to El Paso, worked as a maid in a brothel, met her husband John and married him. There was vague discussion of a child. For years, I searched for the documentary evidence and slowly, as I went through census records of both the United States and Mexico, birth and death records, and newspapers, her story began to appear. That’s how history is recovered—small bit by small bit until the story begins to unfold. Years ago, when I lived in Tucson, I stayed up to witness a meteor shower. Laying back on an outdoor lounger, I stared at the black sky. I saw only darkness and I was disappointed. But, I decided to be patient. Slowly, my eyes focused on one meteor streaming across the sky. Then another and another. Soon, I could see the shooting stars crisscrossing the sky. That’s how history is. It takes patience to finally see the bigger picture. In 1919, twenty-year-old Felicitas Leyva crossed the border from Chihuahua to Texas, bringing her four-year-old son Pascual Molina. During her relatively young life, she had moved many times, first from la Hacienda de Dolores in Chihuahua where she was born to Zaragoza, Durango where she married Gilberto Molina to El Paso, Texas and eventually to Ciudad Juárez where she died in 1948. Her family began their migration throughout the Mexican North before her birth as shown by the birth of her siblings in Durango, Chihuahua, and Coahuila. Sometimes we have the image of our ancestors living in a village or town for generations and that is true for many. For others, however, internal migration or transnational migration began generations ago. Felicitas’ early life was shaped by the Porfiriato and the changes occurring throughout the country. Along with countless other rural families, Felicitas’ family moved from place to place in the 1890s. The 31-year long rule of Porfirio Diaz pushed the poor to seek work on haciendas and in cities and internal migration within Mexico grew during Mexico’s so-called “modernization.” By the time Felicitas crossed the border into El Paso in 1919, she had moved many times. Felicitas was born during her family’s time at La Hacienda de Dolores, a colonial-era hacienda dating back to the early 16th century, located near present-day Jiménez, Chihuahua. Once a Jesuit property, by the mid-19th century Dolores was a “large estate with well irrigated and cultivated fields,” according to A. Wislizenus, a physician with Colonel Doniphan’s expedition in 1846-47. Throughout the 19th century, government reports mention attacks on the Hacienda by “indios bárbaros del norte.” By the time of Felicitas’ birth in 1899, the area was known for its textile manufacturing and its flour mills powered by steam engines. In 1910, the day before the official beginning of the Mexican Revolution, Pascual Orozco and his troops, comprised of Maderistas and anarchistas, attacked the hacienda and he was named head of the Maderistas in the region. Felicitas was 11 years old. In the succeeding years, as Felicitas entered adolescence, the area around Dolores and Jiménez was the site of much Revolutionary activity. In later years, Felicitas’ siblings and nephew would proudly say that her father Quirino Leyva provided horses to Pancho Villa. Felicitas' father, Quirino Leyva. On December 29, 1914, at age fifteen, Felicitas married Gilberto Molina in Tlahualilo de Zaragoza, Durango and five months later gave birth to a son, Pascual. Tlahualilo de Zaragoza, part of la Comarca Lagunera, was originally inhabited by Indigenous peoples such as the Rarámuri and the Tepehuanes. In 1851, two Spaniards founded the first 19th century settlement in the area. By the late 19th century, it began to produce agricultural goods and in 1891, the first cotton was harvested. In 1897 a railroad was built to connect Tlahualilo to Eagle Pass, Texas. At the time the Mexican Revolution broke out, Tlahualilo was a thriving agricultural area, connected to the United States via the Ferrocarril Internacional, with ties to both Eagle Pass and El Paso. Pancho Villa was a frequent visitor to Tlahualilo, making his first grand entrance to the town in 1912, an act that the town still celebrates, and it was one of the haciendas he asked for when negotiating the end to fighting in 1920. It played a significant role during the Revolution and throughout the Spring and Summer of 1914, Villa sent significant number of troops to Tlahualilo in order to stop the federal troops from taking control of Torreon. I wondered how and why Felicitas moved from Dolores to Tlahualilo to marry Gilberto so I explored the relationship between the two places in the context of the Revolution in 1914 and 1915. In 1914, Villa controlled the state of Chihuahua. He was the provisional governor, in fact, and at the height of his influence and popularity. In 1914 and 1915, Villistas were in Jiménez (la Hacienda de Dolores) and Tlahualilo. With 50,000 men in la División del Norte, perhaps Gilberto was a soldier. One of the most common stories about troops entering a town relates to the fear it struck in the hearts of girls, women, and their parents. Troops kidnapped women, raped them, and sometimes their families never saw them again. The stories that relate the ways in which families protected the girls of the family when troops (either federal or revolutionary) arrived show their ingenuity fueled by fear. Perhaps one of the most terrifying accounts I’ve discovered through my research was the story related by Manuel Servín Massieu in an oral history published in 1985 by the Instituto Nacional del Antropología e Historia. Servín recalled the gripping stories which his elderly relative Celedonia often told him of her youth in Zacatecas during the Revolution. One day in the fall of 1916, she and several other young women were drawing water from a well when a commotion started. Soon, several of their parents appeared, "todos pálidos y asustados,” pale and scared, because Villistas were on their way to the rancho. To hide the girls, the parents made them climb down the wooden ladder which led to the interior of the well. Celedonia remembered that the well was so deep that a stone thrown into the well would take ten minutes to hit water. Afraid of falling into the dark depths of the well and afraid to leave because of the Villistas (who their elders had warned would "steal them and take them by force" or "would kill them and throw them to the side of the road"), the girls hid "con la muerte abajo y con la muerte arriba.” If they came out of the well, they could be killed. If they fell into the depths of the well while hiding, they would drown. It was indeed a case of “death below and death above.” After throwing them some shawls and a few tortillas, their parents covered the mouth of the well with boards and dirt. Such measures evidence the terror with which parents and girls viewed the coming of “la bola." We often romanticize the Mexican Revolution and the role of the soldadera, La Adelita, but the reality for many girls and women was horrific. Was Felicitas taken by Gilberto as part of the "spoils of war," as were so many women? Did she go willingly, following him from Chihuahua to Durango where they married in December of 1914? We probably will never know but we do know well that the atmosphere for women was one of fear, constant threats, and trauma. She was four months pregnant at the time of their marriage in Tlahualilo. Famous photo of Mexican Revolution federal soldier with his wife and child. No documentary evidence tells us what happened with Gilberto after the birth of their son. Was he killed? Historians estimate that 1 million Mexicans died during the Revolution so it is a possibility. The flu epidemic of 1918 killed another 300,000 Mexicans. Did the terrible illness take him? Is that why Felicitas came to the United States the following year? Perhaps Gilberto escaped to the US-side of the border, took another name, started another family and lived out his life here. We simply don’t know.

We know that Felicitas reported to the census enumerator that she crossed the border in 1919. We know that she met John Lucas that year and married him in 1920. In 1924, Felicitas was living in Juárez and acquired a local border crossing card. She had dropped Leyva and took on her mother’s maiden name, Fierro. By1930, both Felicitas and John were married to different people. John was married to Lola B. Lucas and still living in El Paso. The Census recorded that John’s household included his son, John Jr. Felicitas was married to Saturnino Chasco and living in Juárez with her husband and her son, Pascual. There is a twist to the story, however. A 1921 Texas birth certificate shows that John Jr. was the son of Felicitas (whose color was listed as “Spanish”)and John Sr. (whose color was listed as “Negro”). As Felicitas returned to Mexico, relocating to Ciudad Juárez with her older son Pascual sometime before 1924, John Jr., or Johnny as he was called, stayed in El Paso with his father and eventually his step mother, Lola. Finding the birth certificate punched me in my gut. Without the presence of this birth certificate, it would be easy to assume that Lola was his biological mother. They are listed in the federal census together and in John Sr.’s obituary. My first thought was that Felicitas was not allowed to keep her son. My second thought was that Felicitas did not want to return to Mexico with a Black son. Either scenario is heart-breaking. Did John Jr. know he had a brother on the other side of the border, Pascual? Did he see his birth mother? Did she want to see him? How could a mother leave her child? These are the same questions I had asked about myself and my birth mother and my sister through much of my life and that’s how interrupted stories work. The fragmented stories that haunt us, the ones we can’t let go of even if we have only fragmentary knowledge, may be the very ones that speak directly to our lives. Just as I came to understand and forgive my biological mother Guadalupe for leaving me, I believe that Felicitas also needs understanding and compassion. Bridging the interrupted stories in our families allows us to acknowledge, forgive, and love the generations before in order to heal ourselves and the generations to come. Bridging the ruptured stories allows us to understand our connections among each other, both in tragedy and hope. Finding John Lucas and Felicitas Leyva permitted me to see how two very different individuals, divided by nationality and race, came together amidst their deeply traumatic experiences, seeking a better life and having hope for the future. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022