|

The Rio Grande/ Rio Bravo that divides El Paso and Ciudad Juarez. Photo from Wikimedia Commons. On July 23, a truck holding dozens of migrants, dehydrated and desperate, was found parked in a San Antonio Walmart parking lot. Ten migrants died. The tragedy made national news. Within days of this horrendous discovery, another heart-breaking story emerged in my own city. It has received little coverage outside of El Paso and Ciudad Juarez although it is equally tragic. Five people died trying to cross the Rio Grande/ Rio Bravo from Juarez into El Paso in the week after the San Antonio deaths, including a 37 year-old woman, a 15 year-old girl, and a 16 year-old boy. The dead were from Guatemala. This year ten people have drowned trying to cross the river. The river that has brought life to so many over centuries now brings death as governmental policies and immigration laws make it a barrier rather than a place of gathering. Because of the border fence, children in my community haven't even seen the river. Friday, Bishop Mark Seitz held mass at Sagrado Corazon Catholic Church in El Segundo Barrio in honor of the five who had died. the Detained Migrant Solidarity Committee held a candlelight vigil the same night. El Pasoans came together to mourn these unnecessary deaths, to pray for those who died so far from home. I too mourn their deaths. I grieve the end of their dreams. The sister of the young woman said she wanted to go to school. Her dream was an education. Photograph by Luis Hernandez. Central Americans who make it to the US border have traveled a dangerous 1,000 miles, facing violence, including rape. They are preyed upon by gangs and smugglers. They are robbed by criminals and government officials. Like in San Antonio, trucks filled with once hopeful migrants are found abandoned by the smugglers in Mexico. Some almost make it, like those who drowned last week. Others cross and are deported. Central American migrants first came to the public's attention three years ago. Until then, migrants on our southern border were painted with the broad stroke of being Mexican. It changed with the arrival of thousands of children. In an eight month period from October 2013 to June 2014 50,000 Central American children crossed the US-Mexican border. In June of that year, President Obama met with President Peña Nieto to discuss ways to improve the root causes of the migration: gang violence, lack of economic opportunity, among others. Although the United States denies pressuring Mexico, two weeks later Mexico announced Programa Frontera Sur. It was touted as a program that would protect migrants and help manage the porous border between Mexico and Guatemala. US funding for Programa Frontera Sur was critical to its implementation. According to Human Rights Watch, the U.S. State Department was expected to provide $86.6 million to Mexico to support immigration enforcement the year it was announced. For FY 2015, Obama requested $115 million, which was increased by Congress by an additional $79 million. The US has also provided technology and training. Programa Frontera Sur has done anything but protect migrants; rather, it has made life more dangerous. Now the trains, la bestia, are almost empty because of changes that included low-hanging concrete barriers making it impossible to ride the top of the trains and concrete walls making it difficult to jump on to the trains. Walking has become the new mode of transportation for Central Americans making their way to our border. Smugglers have new opportunities to exploit desperate people since the program was put into place. Migrants are more vulnerable than ever to gangs. Migrants report that there are more rapes and more robberies. Since the Obama administration, our southern border has moved a thousand miles to the south. (For all my searching, I couldn't find any information on the Trump administration's view of Programa Frontera Sur.) Do such deterrents work? They may stop some people. The economic situation in the United States usually stops many more. We know that they do make crossing much more deadly for everyone. We have seen that in El Paso. In the 1990s, El Paso was the laboratory for immigration policies such as Operation Hold the Line, instituted by then Chief of the El Paso Border Patrol Sector Sylvestre Reyes. The 1993 initiative placed Border Patrol vehicles along a twenty-mile stretch of the border, each vehicle within site of the other. Detentions in the area decreased and it became a model for other initiatives along the US-Mexico border. But it didn't deter desperate people from attempting to cross. It only pushed them to more dangerous areas like the Sonoran Desert that encompasses the Mexican state of Sonora and Arizona on the US-side. People walked in the desert, dying each day of dehydration and heat. Their internal organs "cooked" as the desert heat made its way into their bodies. People are still attempting that dangerous crossing. Coming to the United States is not a decision taken lightly. It is not a decision made on a lark. Mothers have to decide whether to leave their children with relatives in the hope that they will someday be reunited. Or they make the decision to take their children with them, possibly exposing them to danger. Leaving family and friends and everything that is known is a sacrifice that allows us to measure their desperation. The drownings of five Central Americans trying to cross our river last week is a personal tragedy for their families back home. It is also a sign of the political tragedy of our immigration policies that have pushed our boundaries further south, that have treated people like statistics, and that have denied their humanity.

0 Comments

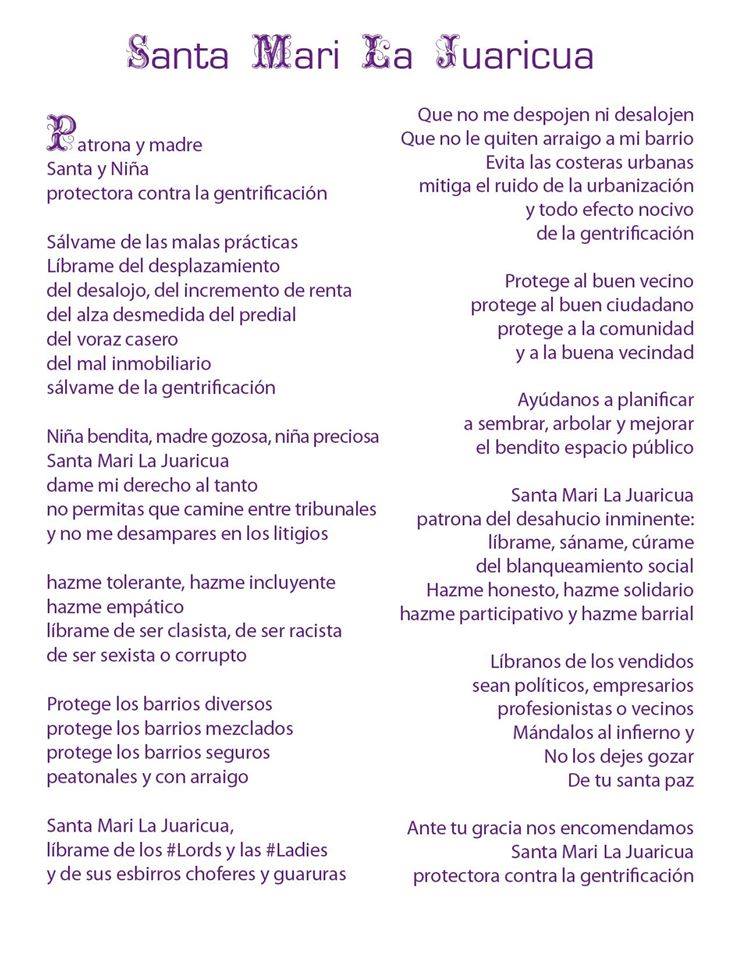

Altar de la Cofradia de Santa Mari la Juaricua from Facebook I have always loved saints. Saints canonized by the Roman Catholic Church. Folk saints created by the people, especially the poor. Sacred places visited by the gente. We pray to santos to help us with our daily problems, the issues that seem overwhelming and beyond our own earthly capabilities. We pray when we need hope and guidance. When we need something outside of ourselves. Now, in Mexico City, a saint who fights gentrification has arisen-- Santa Mari la Juaricua. Her birth place is Colonia Juarez and Santa Maria la Ribera in el DF where people pray against displacement, gentrification, increasing rents, and high property taxes. Mexico City, with its population of 21 million people, is facing "development" projects whose descriptions resonate with those of us opposing displacement and gentrification in our own communities: revitalization, "quality of life," "progress," and other positive-sounding phrases that mask suffering and inequality. Colonia Juarez and Maria la Ribera emerged during the late 19th century during the Porifiato as elites began to move out of the historic center because its colonial buildings were not modern or desirable anymore. The new areas were filled with new homes, hotels, restaurants and bakeries. A hundred and thirty years later, there are still signs of wealth but now there are also the poor. In October 2016, artists Sandra Valenzuela and Jorge Baca created Santa Mari. Baca is a fourth generation resident of Santa Maria la Ribera. Both Valenzuela and Baca have witnessed the destructive effects of gentrification. Santa Mari la Juaricua is much more than the creation of two artists. She has brought neighbors together to organize against gentrification. She has concientizado residents and given them hope. Peaceful marches have been held in her name. She has brought together hip hop artists and long time community organizations, men and women, children, Indigenous people and mestizos. Primera procesion de Santa Mari la Juaricua from Facebook. Today, as my own community faces a legal battle against our City government who had entrenched themselves to displace our elders and demolish our historic buildings, I pray to Santa Mari la Juaricua: Proteje al buen vecino, proteje al buen ciudadano, proteje a la comunidad, y a la buena vecindad.

Today marks 62 years since fourteen-year old Emmett Till was abducted and violently murdered by two white men who never served time after a white woman lied about Emmett's actions towards her. This week would have been his 75 birthday. His brutal murder while visiting relatives in Mississippi from his hometown of Chicago is widely credited with helping invigorate the Civil Rights Movement. I've been thinking about Emmett all year. First, came the news reports that the woman at the center of his murder had lied. Then came the controversy over the white artist who portrayed him, laying in his coffin, unrecognizable. Was she profiting off Black pain? Then recently, the historical marker at Bryant's Grocery that tells the story of his abduction and murder was defaced. It was rededicated a few days ago on his birthday. In honor of Mamie Till's statement that the men who murdered her son "became inconsequential" to her and that "they didn't even exist," I will not name them here. As I've reflected on Emmett, it's brought me to reflect on his mama, Mamie, who courageously demanded an open casket at his funeral. She provided photos of his disfigured, bloated body to the media. She wanted people to truly see what had happened to her beloved boy. With Mamie, there was no turning away from the horror experienced by Black people in 1950s Jim Crow Mississippi. There was no sanitizing the truth. Mamie Elizabeth Carthan was born in a small town in Mississippi in 1921. Shortly after her birth, her father moved the family to a town outside Chicago. The "Great Migration" of African Americans from the South to the North brought six million to cities like Chicago. She entered an abusive marriage at age 18, became a widow at age 24, and at 34 became the grieving mother of her son Emmett. Often, that is all we remember-- the photo of Mamie at her son's funeral, eyes shut tight in pain. It was not the end of her life nor the end of her love as a mama. Iconic Associate Press photo of Mamie Till at her son's funeral. Following the trial, the NAACP asked Mamie to tour the country lecturing about her son's murder. In 1960, she graduated from Chicago Teacher's College, became a teacher, and in 1975 earned an MA in Administration at Loyola College in Chicago. She organized against the death penalty. She fought for racial equality. In Chicago public schools, she created the "Emmett Till Players," a student group that continue today performing speeches by Martin Luther King, Jr. and other Civil Rights Leaders. When Emmett was murdered, Mamie said "When people saw what happened to my son, men stood up who had never stood up before." His murder, the biggest tragedy of her life, made her stand as well. She said she found her peace in working with children, in helping them achieve the extraordinary. "We must impress upon our children that even when troubles rise to 7.1 on life's Richter Scale, they must be anchored so deeply, that though they sway, they will not topple." That is radical love. To face the unspeakable horror of hatred and dedicate your life to love. It is not turning the other cheek. That would allow things to remain the same. It is to meet inequality with hope and action. It is to lose your only son and still find it in your heart to mother generations of other children. Today, on the anniversary of Emmett Till's abduction, I honor the memory and the work of his mama, Mamie Till-Mobley. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022