|

Artículo 39, Monumento Benito Juárez , Cd. Juárez (Photo courtesy of Maintain Studio) Christian and Ramon Cardenas are LxsDos, artists living and working on both sides of the border in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. Walk through El Segundo Barrio or Downtown or Union Plaza or Ciudad Juarez and you will see their art. The faces of the everyday people of la frontera will look out at you from their work. When I first saw their mural, "Sister Cities/ Ciudades Hermanas," portraying El Paso and Juárez as two hermanas with their hair braided together, it inspired me to write my first blog post about my twin sister and me. It reminded me of my own life as a sister and as a fronteriza born on one side and raised on the other. (You can read that post here.) That's what their art does-- inspires, tells stories, recognizes and pays homage to the everyday people of the border, and helps us think about our own stories. We as border people are reflected in their art. Our culture and our vidas cotidianas are in their art. And their art talks to us about power and change. The piece above, "Artículo 39," and the piece below, "Ayotzinapa Tribute," are potent statements about the power of el pueblo, the people, and they are calls for change. Together, they point to the contradictions of power and the suffering of the poor. Article 39 of the Mexican Constitution says (translated into English): National sovereignty is bestowed essentially and originally upon the people. Every public power derives from the people and is instituted for their benefit. The people possess, at all times, the inalienable right to alter or change their form of government. In the piece, warrior women stand, demanding their rights and their power. The piece below, "Ayotzinapa Tribute," uses the ancient Mesoamerican image for life into death with the face of one of the college students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers School in Guerrero in the center. In 2014, 43 students were disappeared after being attacked by military and law enforcement as they headed to Mexico City on a bus. For three years, their parents have sought answers, saying "You took them alive. We want them back alive." In the piece below, the final stage from life to death is the image of a jaguar, a warrior. Even in their absence, the young Indigenous men of Ayotzinapa are warriors for justice, just as they were while attending college. “Ayotzinapa Tribute” by LxsDos. Photograph © Federico Villalba, all rights reserved. I met Christian and Ramon last year when we first began working to protect Barrio Duranguito in South El Paso, the oldest barrio in El Paso and under threat of demolition by the City of El Paso. LxsDos were generous with their talent as we began producing posters and banners. I fell in love with their art. It spoke to my heart and it spoke to my sense of the beauty of this border. Not a romanticization of the border. But the beauty of our every day life. Below on left: Banner designed by LxsDos. On right: poster designed by Zeke Penya and LxsDos. LxsDos, Chris and Ray, believe that street art brings art to the people of barrios on both sides of the border. Study after study has shown that working-class people in the United States do not go to museums. It's not because they don't love art. It's because they don't feel welcomed for many factors (language or entrance fees, for example) or their time doesn't allow them. Working-class folks often work more than one job or work graveyard shifts. Art becomes a luxury, then. For LxsDos, art should not be a luxury. It should be a right. Their street art brings the beauty of art to the people... on both sides of la frontera. Foundational to their work is the understanding that the borderline created in 1848 divided a land and a people that were and in so many ways remain tied together. The creation of the modern dividing line made us into migrants. Both Chris and Ray have experienced crossing borders: Chris is Mexican and Ray is Filipino. I've always been a woman of words. Words are how I see the world. In the past few years, I've worked at developing my visual skills and the way I observe the world through my eyes. It was experiencing the power of art that began my journey of looking at the world, rather than only listening to it. The art of LxsDos has been part of that journey. I am grateful for the fronterizx vision of LxsDos. Artists Ramon and Christian Cardenas. Photo: Itzel Martinez for Remezcla.

2 Comments

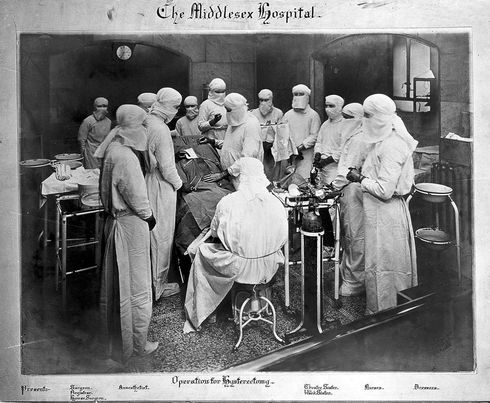

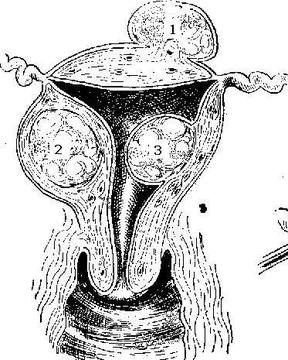

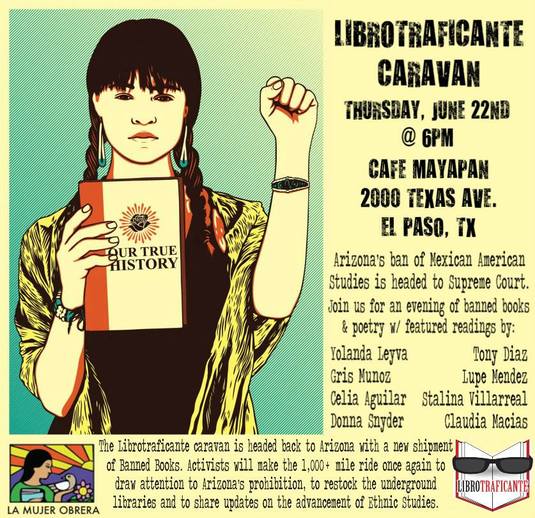

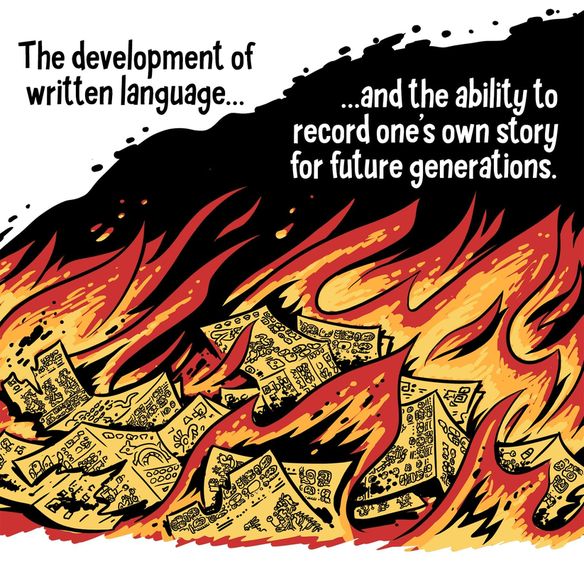

Operation for hysterectomy at Middlesex Hospital courtesy of Wikimedia Common Recently, I read a post, "Womb War: Reproductive and Sexual Health issues Among Women of Color," on Dr. Candice Nicole Hargons' blog. I discovered the post because of a private Facebook group that I am part of for women of color in academia. Her post drew many, many comments from WOC connecting their experiences with racism and sexism to the appearance of uterine fibroids. Dr. Candice Nicole doesn't make this connection in her post but does ask why Black women are three times more likely than White women to experience fibroids. You can read her post here. Latinas experience fibroids at about the same rate as White women according to the very few studies conducted on Latinas. We also know that over 70% of all women over 50 have fibroids, many not experiencing symptoms. We know that women's race and income influences the diagnosis and treatment of fibroids. Reading Dr. Candice Nicole's article brought back memories of my own struggle with fibroids, which were diagnosed in my thirties. It brought back the memory of a piece I wrote shortly after my hysterectomy in 2000. I offer this piece to you today. A 1913 image of uterine fibroids courtesy of Wikimedia Commons “Carry our stories carefully/ Wrap them in soft red cloth/ And place them against your heart.” From ``El Regreso: An Invocation” Growing up I became the somewhat reluctant carrier of women’s stories—mothers, aunts, grandmothers, sisters. They were mostly stories of pain, abuse, and poverty. The kind of stories that generations of women have kept secret or shared in whispers with other women, sometimes in shame, sometimes in desperation. The kinds of stories that speak of the weariness of the soul, yolmiquiliztli our ancestors called it. The young mother, tormented by her father’s incest, whose tortured mind wouldn’t allow her to keep her children, wandering self-destructively through life wondering if they knew that she loved them. The grandmother who died at forty, disillusioned at her impoverished life in the new country, always remembering the life she had left behind in Chihuahua before la Revolución took everything away. The tía abuela who gave birth to a baby boy, alone in a small dirty tenement bathroom in el Segundo Barrio, immediately handing him over to a stranger to raise. The tiny baby girl who spent the last days of her life with her stomach cramping, the burning pain of an intestinal disease filling every inch of her fragile body, who found it easier to let go of the spark of life than to fight the pain of the extreme in the sandy desert outside of Cd. Juárez where half a century ago clean water was and continues to be a luxury. There were also stories of fighting back, of strength, and of humor. The young wife who hit the border patrol agent with her purse for disrespecting her dark skinned husband, in his army uniform, as they crossed the border. The sister who pushed her wife-beating brother-in-law out a two-story window in defense of her older hermana. The young girl who went each evening, her heart sparkling, to find a secret love letter from the young man who courted her, hidden between adobe bricks, away from disapproving parental eyes. Hesitantly, I listened to the stories over and over as a girl. Having heard them repeated over and over, I memorized them unwillingly. Over the decades, these stories made a home in my body where they settled, often uncomfortably, in my most vulnerable women’s places—my uterus and my heart. From adolescence on, I bled uncontrollably each month, cramping so violently that sometimes I fainted. By my thirties, tumors had begun to grow in my uterus, increasing the monthly pain. Doctors urged me to have a hysterectomy.[1] Hysterectomies, a decade ago as now, were the frequent answer to such conditions. My heart, no yollotl,—the place that our ancestors saw as the residence of vitality, knowledge, will, and affection—suffered as well. For years, I experienced yolmiquiliztli, the weariness of the heart, literally the “death of the heart.” I believe it was passed on from generations of women before me, some of whose stories I knew and others that I did not. I carried their pain in my cells as if it were my own, and it was mine although I had not directly experienced their suffering. [2] I tried to awaken my heart and deaden the pain through external means, self-medicating in all the ways that modern society offers us. However, it only served to separate me more from my corazón and from myself. The more I tried to forget the pain, to distance myself from the stories, the more I forgot my true self, my human self. Our ancestors had a word- yollopoliuhqui, which meant “lost from the heart” or forgotten. It also meant “strayed from the heart.” or careless. I was both. Like so many, I took risky chances. I didn’t listen to my instincts. And I often lived in fear. One day, in my mid-thirties, returning from an appointment with a persistent doctor who insisted that removing my uterus was the only way to stop the pain, I had an idea. What if the tumors represented the women’s stories that had nestled in the tissue of my uterus, and what if writing them down allowed my body to release the painful, hard tumors? I began slowly, hesitantly writing them. It was difficult. I had carried them for so many years, keeping them secret as I was taught. I felt fear and guilt for putting the stories down on the paper, but I continued over several weeks. When I returned to the gynecologist’s office a couple of months later, she was surprised that some of the tumors had disappeared and that others had shrunk. I was elated, but stopped writing the stories. I don’t know if it was the shame and secrecy that the stories embodied or whether, after so many years separated from my heart, I didn’t have the discipline or the self-love to continue. "The uterus," Berlin 2013 by Denis Bocquet, Flikr A decade later, the tumors were back and, again, doctors began to urge me to have a hysterectomy. At age 44, I finally agreed and my uterus was removed. I was traumatized and saddened following the operation. Physically, it took years for me to feel “normal” again. But the shock of having lost my uterus pushed me into action and I returned to writing the stories. Out they came, mostly as poems, and I began to read them out loud in public and to publish them. Suddenly I could hear the generations of women before me who began to call on me to tell their stories in ways that were truthful and respectful. My heart began to open again. Yolmiquiliztli, the weariness of heart, the death of the soul, has another aspect. The great maestro of our culture, Arturo Meza Gutiérrez, writes of the concept of miquiztli, death, as inevitable. Yet he also calls it “el sueño reparador que genera ideas positivas.” My death of heart had transformed into a period of rest just prior to the emergence of a new life. Like madre tierra, who appears dead and lifeless during winter, only to reemerge green and filled with life in the spring, telling the stories had brought me back to life, back to my humanity, and back to myself. My heart knew that healing was possible; I felt it and I worked towards it. Acknowledging the stories, writing them, and telling them had initiated the process of healing. Not just for me, but also for those women whose stories I had carried for so many decades, painfully in my body. The trauma of our stories, as individuals, as families, communities, peoples, nations, as humanity, cannot be ignored. It cannot be self-medicated into oblivion. I learned that to remember, in a conscious way, was part of the healing. I learned that to tell the stories in ways that honored that generations that came before us was to heal. I learned that my heart/our heart could awaken again. [1] Today, approximately 600,000 women in the United States endure hysterectomies each year. Women’s health advocates argue that up to 75% of these life-changing surgeries are unnecessary. They are among the most common surgeries for women. [This is a statistic from 17 years ago. A more recent statistic cites 85% to 90% of hysterectomies as being unnecessary.] [2] Today social workers, psychologists, and other scholars write about historical trauma. The suffering of our ancestors and our peoples whose effects continue to be felt for generations, even if the precise details have been lost or sometimes purposefully forgotten. Today, I am pleased to share my comments welcoming the Librotraficante Caravan to El Paso on Jun 22, 2017 at Café Mayapan. I am honored to speak tonight as we welcome the Librotraficante Caravan to El Paso. The Librotraficante campaign and their “wet-books” rose up in defiance to Arizona’s banning of ethnic studies in high schools through HB 2281 in 2010. In 2012, the Librotraficante Campaign traveled from Houston to Arizona, bringing banned books and a desire to support ethnic studies across the United States. The attacks of ethnic studies have continued since the passage of HB 2281. Earlier this year, HB 2120 proposed to ban ethnic studies in Arizona community colleges and universities. Fortunately, the bill died. The ban of ethnic studies in Arizona is now scheduled to be reviewed by the State Supreme Court. Were it not for the work of Librotraficantes these attacks on our right to know our history may not have received as much attention nationally as they have. I grew up on the border in the 1960s, raised by parents who were born during the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Crossing the river during the Mexican Revolution, photo by Otis Aultman, courtesy of the El Paso Public Library I grew up on the border in the 1960s, raised by parents who were born during the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Growing up, I listened to stories about crossing the border at a time before the Immigration Act of 1917 created a barrier to legally entering the United States and before the Border Patrol existed when one could easily move from one side to the other. I listened to stories about my mother’s clash with her conservative father when she told him she wanted to cut her hair into a bob and when she sewed a red dress, which he promptly tore to shreds because señoritas decentes no se vestian de rojo. I heard about how difficult it was to survive during the Great Depression when my parents, a young married couple, had only one egg to share for nourishment for the whole day. And I heard my mother’s sorrow as she recounted waiting for days and weeks and months for her husband, her brother, and her nephews to return from World War II. These were the stories of my family. Told over and over until they were familiar and comforting. Jerry Leyva and Esther Chavez, my parents, El Paso, Texas 1929 “History,” as scholar Vicki Ruiz writes, “was a grand adventure, one that began at the kitchen table listening to the stories of my mother and my grandmother…” (Vicki Ruiz, From Out of the Shadows: Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America, p. 164) Unlike Ruiz, however, it took me a long time to understand that the family stories were part of a grander national and international history. In the 1960s and 1970s as I went through elementary school and high school, public education was designed to keep us in our place. Across the Southwest, Mexican American children faced harsh consequences ranging from detention to corporal punishment for speaking Spanish on school grounds. We were funneled into manual labor and away from higher education. We never saw ourselves reflected in our studies. When, in 1973 my high school unexpectedly offered a course in Mexican American literature, I registered for it excitedly only to find the teacher who had no expertise in Chicano literature and believed that, as a people, we were fatalistic and docile. Public education knew how to keep us in our place as a people who the power structure said didn’t belong as part of the history of this nation. An image of book burning and its consequences for the Mayan people from TheNib.com There is a reason that conquest and keeping control of people always involves first destroying their knowledge of their own culture and history and secondly, destroying their ability to recover it. In 1528, future Bishop Juan de Zumarraga burned countless Mexica and other Nahuatl books. Similarly, in 1562, Fray Diego de Landa ordered the burning of all Mayan books. As a result of this zealous book burning today we have less than twenty that survived, some in fragments. After the books were destroyed, missionaries such as Landa went on to write their own accounts of Indigenous culture and history, all through a European lens. Another example of keeping people “in their place” by denying them knowledge are the laws that made it illegal to teach enslaved people how to read. In 1831, the North Carolina legislature passed a law that forbade teaching enslaved people to read or write or to tell them books. The law began “Whereas the teaching of slaves to read and write, has a tendency to excite dis-satisfaction in their minds, and to produce insurrection and rebellion, to the manifest injury of the citizens of this State,” as a justification for the punishment of fining a white person and whipping an enslaved person for daring to teach someone to read.  Professors Rudy Acuña and Gabriel Gutierrez during my visit to CSUN, 2017. To keep us from reading and learning our history is to take away our ability to know ourselves and our true place in the world. It leaves us vulnerable to being told where we belong. But thanks to the work and sacrifice of generations before us and people like the Librotraficantes today, we can claim our own place in the world. For me, it began in college as I took my first Chicano Studies courses at UT Austin in the mid-1970s. There I was introduced to books such as Rudy Acuña’s Occupied America and Elizabeth “Betita” Martinez’s 450 Years of Chicano History, which later became 500 Years of Chicano History. These two books, both now banned in Arizona, had such an impact on me that I have carried those well-worn copies from place to place for over 40 years. I brought them with me tonight to remind myself of what my 19-year-old self experienced when I was introduced to them.

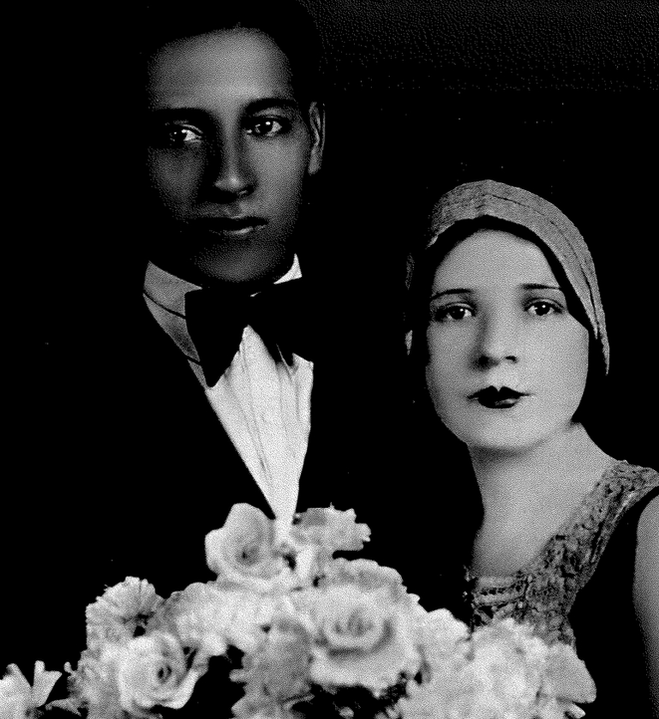

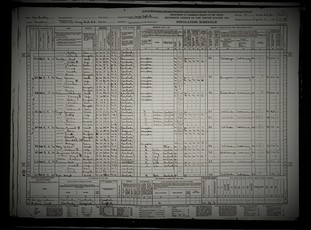

In my Chicano Studies classes, I learned that those well-loved stories were history. My mother’s story of her red dress reflected the history of young women who resisted their immigrant parents’ insistence on remaining traditional while they were growing up within American popular culture and transforming gender roles. The song, “Las Pelonas,” collected by Mexican anthropologist Manuel Gamio in the 1920s said, “Los paños colorados/Los tengo aborrecidos/Y ahora las pelonas/Los usan de vestidos.” My mother was part of history. The most profound realization occurred when I read about the repatriations of the 1930s. I knew that relatives from both sides of my family had returned to Mexico during the Depression, including my U.S.-born aunts, uncles, and cousins as well as my grandparents Agustin and Cruz. I never understood why they went through the suffering they did, returning to Mexico and then working to return to the United States. I never understood why I was born in Mexico when my family had been here for two generations. It was an emotional moment when I read about the federal deportation campaign, the anti-Mexican violence and the pressure to leave the U.S. experienced by our community, including U.S. citizens, in the 1930s. My family stories were suddenly contextualized in a larger history that transcended our family to include the Mexican American community and the history of two nations. Perhaps it was at that moment that I decided to become a historian, although it would take another 10 years for me to make that commitment. What I do know is that at a time when public education was intent on putting us in our place, ethnic studies (for me specifically Chicano Studies) allowed me the freedom to find my place in my community, in our history and in the larger history of the United States and Mexico. It gave me the gift of belonging. The next time someone told me “Go back where you came from,” I would know that I was exactly there/ here where I belong. Because of Chicanx Studies, I know my place in the past, the present, and I have a vision for the future of our people. That gift is one that I will always treasure. Coal miners in W. Virgina, 1908. Courtesy of Wikipedia. Well, I was born a coal miner's daughter In a cabin, on a hill in Butcher Holler We were poor but we had love, That's the one thing that daddy made sure of He shoveled coal to make a poor man's dollar. "Coal Miner's Daughter" by Loretta Lynn I always loved Loretta Lynn's song, "Coal Miner's Daughter." I'm not even sure how I ever heard it since it came out in 1969 when I was 13 and listening to the Beatles while my parents played Edie Gorme y Trio los Panchos. Somehow in my youth, I heard it and loved it. Little did I know all those decades ago that my paternal roots were deep in the coal mining country of Kentucky. I knew I was adopted since I was six and about to enter public school. I remember my parents going with me to the principal's office to register me for first grade. When we returned home, they told me about my adoption, at Mrs. Knight's suggestion. "It's important for her to know the truth," she had advised them. They told me about my birth mother, Guadalupe, but didn't mention my biological father. As I grew, I never wondered about my biological father. To me, my daddy was my father and I was a devoted daddy's girl. Jerry Leyva showed me consistent and unconditional love. His stories shaped my worldview. When he went into a coma in 1997, I stayed by his bedside for days. He waited to die until I left to teach on the first day of class. I always think he couldn't bear to leave with me there. Over the years, occasionally, I would hear the family rumor that my biological father "era un Americano," a white man. I never believed it and I never pursued it. Unlike my birth mother who I cried about and raged about internally for most of my life, my birth father was a passing thought to me. I rarely thought about the mythical "Americano." Until I did a DNA test three years ago that is. The results turned my life upside down. The great majority of my DNA relatives who were identified by both Ancestry.com and 23andme.com had Kentucky roots. I couldn't believe it. Kentucky? I threw myself into reading about Kentucky history. It turned out I am related to the "blue-skinned people of Kentucky," have Cherokee ancestors, and come from some of the earliest settlers of the region who arrived in the 18th century looking for land and found the green mountains to be home. While conducting research, trying to understand what it meant for me, a Xicana/Mexicana/india to have a white father, I felt torn up inside. WTF I thought, for at least two years. How could I be half-white? I understood perfectly well the problems with this kind of question, teaching ethnicity and race and identity as I have for so many years. But it was a question that obsessed me, tortured me, and made me wonder about my biological father for the first time ever. My son told me one day to stop suffering. "You're just some random baby to that family. You were raised Mexicana and that is who you are." I never thought being called a "random baby" would bring me such comfort, but I stopped suffering. But I kept hoping that I would know who he was. Then almost three years after discovering my Kentucky roots, my brilliant and generous cousin Melinda Gould, who I had also met through Ancestry.com, completed the puzzle for me through her understanding and experience with DNA and genealogy. I am grateful that she gave me the gift of her time and knowledge; we have never met in person but she feels like real family to me. I still don't understand the mechanics of how Melinda figured it out, but she did. She found out who my Kentucky father was. My "Genetic Communities" according to Ancestry.com. Years ago, I went to meet my birth mother's sister, already elderly, to ask her about my mother. Back then, as I said, I didn't wonder about my father but she wanted me to know that my father "loved" my mother "very much" and that they were both in love. She handed me an envelope with photos, saying "Este es tu papa." When I returned home, I looked at them and realized that the photos represented at least three different men. I just laughed, thinking I would never really know the truth. Until Melinda did her DNA/ genealogical magic. Melinda even told me his name. I could finally start piecing the story together from her research in the historical records. He was a kid in the military who met my mom in Juarez and I was the result. Don Tosti, composer of "Pachuco Boogie" and the first Latino composer to sell a million records, said in an interview years ago that his mother was a young woman in El Paso and his father was a soldier at Fort Bliss. "They went out to dinner one night and here I am." That was me. A kid from Kentucky came to El Paso, met a beautiful teenaged Mexicana in Juarez, and here I am! I didn't know how much pain I had held in my whole life never wondering who my biological father was. To "not" wonder is as painful as always wondering. As Melinda and eventually I continued to search the records, we learned more. He grew up in a Kentucky mining camp. He went on to marry a Kentucky girl a couple of years after I was born. They had several children. Unlike his father who was a coal miner, or generations of farmers who preceded him, he remained in the military for twenty years. He is now deceased. I doubt he knew about me. With this background information, I knew which photo was him. It wasn't the movie star handsome scuba diver or the Latin lover looking man with a moustache and a wicked look in his eye. It was the goofy white boy. I keep his photo out on my dresser now, always looking for a resemblance. 1940 Census from a coal mining camp. I never expected it to be him, but learning it was healed me. Or at least I'm on the road to healing. I don't have a desire to meet his/ my family. Melinda says I will when the time is right. She's probably correct. For now, though, the gift that my cousin has given me is a name, a face, a family history that I can say is part of me. I will always be Jerry Leyva's daughter. He will always be my daddy. Now I can accept that there is a second father that is part of my story. Happy Father's Day, Charles, from your fronteriza daughter. For the past nine months, I have been working in a low-income, immigrant community filled with elders who are being harassed, displaced, and profoundly injured by our city government. Their lives have been turned upside down because real estate developers want an arena that will cost taxpayers dearly. Some elders have remained unbelievably strong in their defense of their neighborhood. Others are scared and confused, rightfully so in the midst of deceptions and threats by property owners on behalf of the city. For months, I have had a sense of urgency, of battle, of giving all to help in the struggle to protect the elders and their barrio. It's taken its toll on me and on my family emotionally, physically, spiritually. I'm stretched thin and exhausted. I'm not complaining. It's been my choice to do this work. I'm just describing what I've allowed to happen. In order to turn things around, a few weeks ago I made a plan to leave town for a few days by myself with two of the dogs and pray and write and think about how to regain some kind of balance in my life. (I'm writing this in the middle of my DIY retreat!) As I prepared to leave home, even packing was exhausting and stressful. Sometimes when I am home alone, I turn on videos and sing at the top of my lungs. It energizes me. So to motivate myself to keep packing, I turned on Shakira videos. Without thinking I started to dance and I danced and danced and laughed. I danced with Shakira!! Photograph courtesy of Yi Chen, Flickr Have you ever watched a child dance? I've seen my grandson suddenly start dancing many times. Spontaneously. Sometimes seriously. Sometimes joyfully. My grandson is a serious boy, a worrier, an intellectual even at age 10 who is mostly in his head. In those times when I have seen him dance, he is filled with a happiness that is rare. When I finished dancing with Shakira last Sunday morning, I understood his impulse to start dancing suddenly. For a few moments I was outside of my own head, feeling my body move to the music. If you've been in any kind of radical feminist or political movement, you've probably seen the quote below from Emma Goldman, famous and infamous anarchist who was born in what is now Lithuania in 1869 and who came to the U.S. in 1885. "If I can't dance, I don't want to be part of your revolution." I never gave it much thought until that morning I was dancing with Shakira.  For those of us who find ourselves in the midst of the suffering of the communities we work with, who confront daily the injustice of power that cares only about profits and not human beings, perhaps dancing itself is revolutionary. How do we take care of ourselves when we are empathic, when our hearts are breaking, when injustice is everywhere, in our neighborhoods, in our nation? Dancing with Shakira that morning gave me a little glimpse of how to care for myself and this week I continue to explore how to regain health and energy for the long-haul, how to honor my relationships with my partner, and children, and friends, and how to continue the work that I love. For those of you who have been in this revolutionary work, how do you take care of yourself?

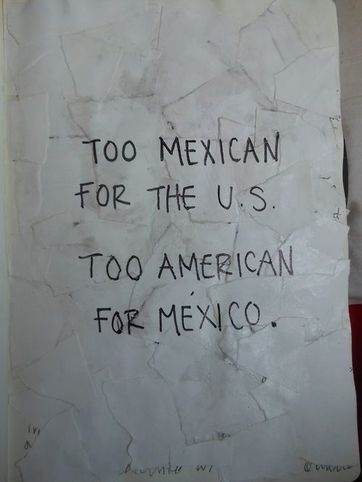

Ni de aqui. Ni de alla. Or is it de aqui Y de alla. Both?

Fierce Fronteriza is celebrating six months! On a cold, snowy day in Denver while attending the American Historical Association conference, I decided to take a leap and finally begin blogging. It has been a wonderful experience. I love it-- I have 15 draft blog posts waiting to be finalized right now. From historic buildings to Braceros, from queer history to Pachuco history. From the past to the present. It's all a part of being a Fierce Fronteriza. In order to celebrate, I want to know from YOU, "What makes us fronterizas and fronterizos?" Is it culture, language, geography, accident of birth, or what? Is there a difference between being a fronterizA or a fronterizO or a fronterizX? Comment below and I'll put together a blog based on your ideas. I can't wait to hear what you think. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022