|

Young woman and old woman from the Codex Mendoza. I’ve been thinking about generation gaps lately. Not just because I have a teenaged granddaughter who rolls her eyes at her parents (fortunately, not at me) but because I've been thinking about political work and where I fit as an aging, lesbian academic. I feel in my twenties on the inside; I still feel the same passions about fighting injustice. I still feel the tremendous sense of hope and potential. I still feel fierce. My external self belies my age. Fibromyalgia keeps me in pain much of the time. Chronic fatigue keeps me tired even when I've slept. My obesity makes it difficult to move sometimes. When I look in the mirror, I cringe-- I have the beginnings of a turkey neck. My memory increasingly fails me. A series of tumors has destroyed my hearing and my sense of balance. It's like they say, aging is not for sissies. I've watched women around me age. It is shocking to go through it. I will never forget the image of my mother standing in front of a mirror in her late seventies, trying to comprehend the changes in her body. She was always a beautiful woman and she was proud of it. That day as I watched her observing herself, she began to weep. She couldn't understand how life had changed so much. How her body had changed so much. She was old. She kept saying, "Qué es esto? Qué es esto?" Aging is incomprehensible even as we go through it. My dear friend who passed away at 95 often told me, "Don't get old, honey." My tia in her 90s often said the same thing. Was death preferable to aging I wondered? A while back I had a conversation with an activist from another city who was telling me about a "sell-out" in their community. The sell-out sounded horrible. When I asked who it was, I was horrified to find that the activist was discussing someone I had known for forty years, someone I had seen organize in low-income communities for decades and whom I admired and respected. Yet, here was this young person dismissing her and her decades of work and sacrifice. It shocked me and it hurt me. In my work as a professor, I am surrounded by young people. I often think how fortunate I am to teach in a community where Mexican culture, with its respect for elders and for maestras, is still vibrant. Since my early fifties, students have told me that I remind them of their abuelitas. And I always took that as a compliment. In my spiritual community, I am called abuela and I am grateful for that sign of respect. Yet, increasingly I see small signs that this cultural understanding is breaking down and it worries me, especially around political work where the generations need each other so much. If the power structure can keep us divided generationally (and along a multitude of other lines) we will be weakened. During Spanish colonialization, one way the colonizers tried to undermine and destroy Indigenous societies was by separating the young and the old. “You don’t need those old people,” they told the young. “You have the power.” By building up the young and diminishing the old, the balance inherent in society fell apart. But the young did (and do) need the elders just as the elders need the young. We complement each other with our gifts. We each bring different gifts. This interconnection between generations is evident in our traditions. You see it reflected in the spatial/temporal understanding of space and time. When my maestras and maestros in Mexico taught me to all int he directions, it was a lesson about the complementarity of relations. The east with its energy of beginnings and masculinity is called in with the west with its energy of completion and female power. When we call in the north, mictlampa, we acknowledge ancestral knowledge and our elders followed by calling in huitzlampa, the south, where we acknowledge the importance of youth and the creativity. Together, we move forward. Separated, we don’t. It is that balance that keeps the universe whole. The four directions that complement each other from the Borgia Codex. A couple of times recently, I’ve heard younger people talk about “their generation” as compared to mine. I am 61 and I came of age in the 1970s. They came of age in the early 2000s. “Our generation fights white supremacy,” they’ve said. That leaves me wondering what they think about the long history of fighting white supremacy that goes back centuries. Sometimes I want to say, “I was fighting white supremacy before you were even born!” and I remember confronting the KKK on the streets of Houston 40 years ago this year. And the generations before me fought white supremacy. Each generation is led to believe that they have invented something new, something better than the generation before. Separating us from our longer history may stroke our egos (we are doing something better) but ultimately, it leaves us functioning in a vacuum. Taking away our history makes us spend energy and time reinventing the wheel. We don’t have the gift of seeing what worked and what didn’t work in the past. Rejecting the older generation is rejecting an important living history. When I teach Mexican American history, I organize the class generationally. (Drawing on the work of Dr. Mario T. Garcia and others. You can see one of his books here.) A generational approach allows students to relate in a more intimate way to the historical content—they can often identify family members who represent some of the generations. It also allows them to see how each generation built upon the previous ones, even while each generation claimed to be different and separate from previous ones. The Mexican American generation gave birth to the Chicano generation, for example. The relationship between the two generations is complex and contentious but the Chicano generation emerged from the Mexican American generation none-the-less. An old photo album with a photo (lower right) that I took during a confrontation with the KKK, 1977. They punched this compañera in the face. The police let them walk away. As I grow older, I need the younger generation. I want to work with the younger generation. They can accomplish what no longer can. It is a joke among my students, but I really do go to bed at 8 p.m. I just don’t have the energy I had even ten years ago. But it is not simply energy that the younger generation brings. They are bright, creative, innovative. Eighty-nine year old Antonia, a community leader in the barrio, often says that she didn’t have children but now she is surrounded by her “children,” the young people of the group. “Son inteligentes y tienen computadoras,” she often brags about them. I understand that pride of how the young people are and what they know and think. I come away from meetings often in awe of their brilliance.

And sometimes, I come away feeling dismissed and judged. I want the younger generation to know that I have worked in community for years and that if I am less active for a month or two, it doesn’t mean I no longer care or that am only worthy of disdain. It means that I can only do what I can do and I can’t do it all. But I do what I can with all my energy and heart. And with decades of commitment behind me. To the young generation, I promise to do my part to listen to you and your dreams and fears. I commit to doing my part to remain non-judgmental of you and to understand your point of view. I promise to show you respect and to remain self-reflective about my own shortcomings. Know, too, that I have a commitment to myself to take care of my own self. I love myself enough to know that I will only work with those who show respect. Respect is the basis for loving across the generational divide. If we work together, the young and old, we are strong. We are in balance. We are unstoppable. This is my great hope.

1 Comment

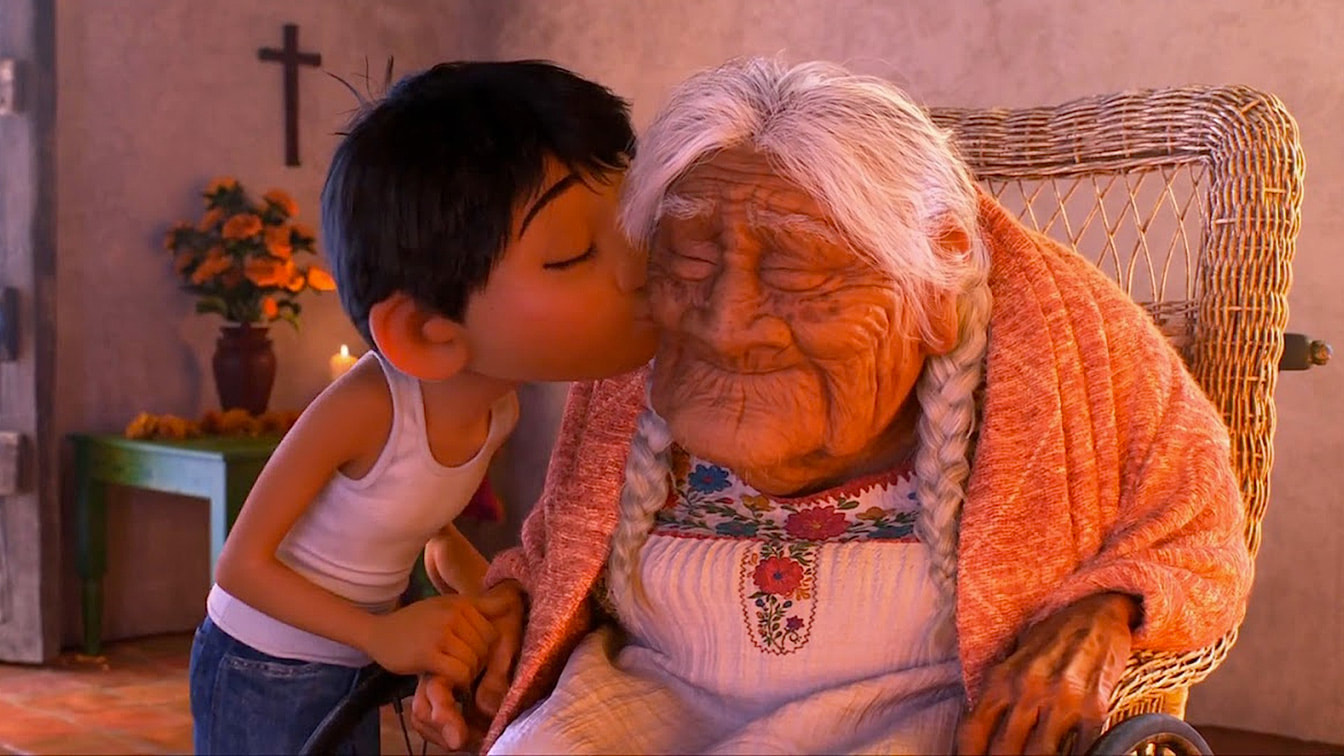

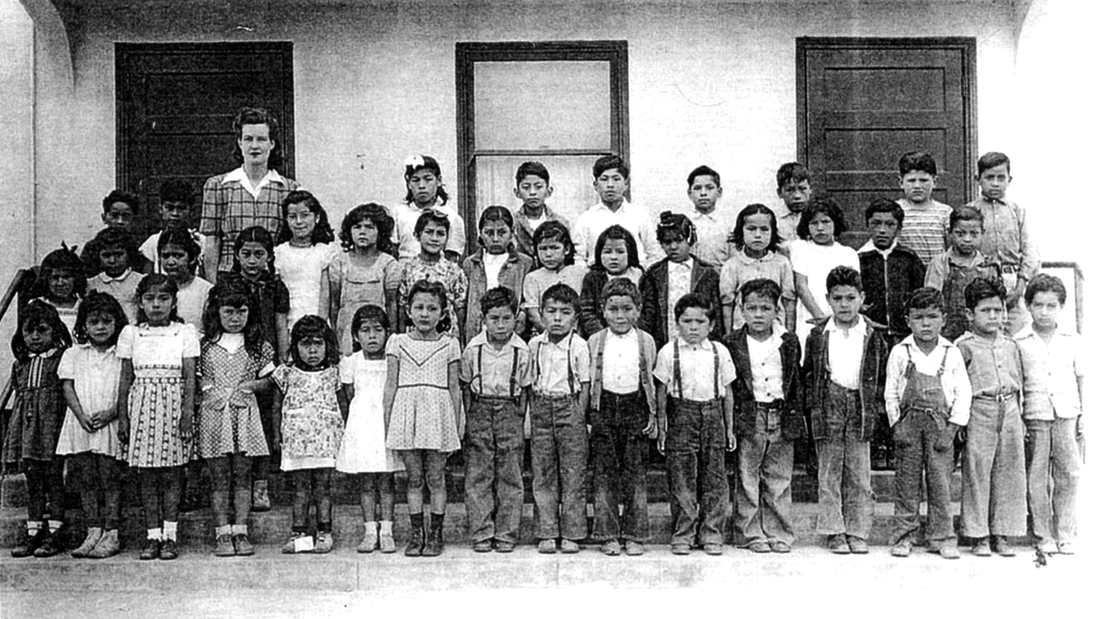

This week Pixar’s movie Coco opened to glowing reviews. I took two of my grandchildren to opening night and at the end of the film, the audience applauded. People sat in their seats during the almost interminable list of people who had worked on the film, intrigued I think by this film that finally presented our cultura in a beautiful and complex way. I think every generation can identify with the film, from the young like my grandchildren who recognized in Miguel their own struggle to follow their own dreams to those of us who recognized the 1950s black and white movies starring handsome Mexican entertainers (in the movie, Ernesto De La Cruz, a handsome entertainer wildly beloved even in the afterlife.) For those of us fortunate to have known our abuelitas or who have witnessed our own parents age, abuelita Coco reached our hearts with her beautiful, wrinkled face and her childlike smile. In the film, the Rivera family, renowned for their skills as cobblers, have rejected music for generations. Coco’s father, a musician, abandoned the family when she was a child and her mother, once a lover of music blessed with a beautiful voice, forcefully eliminates music from their lives. In obedience to the family tradition, five generations of family live without it. As Miguel grows, he must hide his love of music and his talent as a musician and singer, retreating to a secret hideaway, filled with tributes to his idol De La Cruz. The film is framed by el Dia de los Muertos, increasingly popular in the United States as a day of face painting and parades, altar building, and celebration. Traditionally, it is a day when our dead visit us and in a twist, Miguel ends up in the land of the dead, a glorious place of shining lights and shimmering buildings. Accompanied by his dog Dante, the film gives us a nod to Mesoamerican traditions where a xoloitzuintle acts as our guide in the underworld. Left to right: Xolo from Borgia Codex, Itzpa my xolita, and Dante from Coco There are so many ways to write about this film. As I watched the film, alternately laughing and crying, what stood out to me most was how beautifully it presented intergenerational healing. My maestras and maestros have taught me that it is possible to heal across generations, backwards and forwards. As a historian and a healer, I have often reflected on the ways knowing our history can heal us. History is a tool of oppression and of liberation. It is a reflection of power and resistance. Over the decades as an educator sharing little known histories with my students, I’ve caught glimpses of this healing. Once, a student told me that she thought her family was “crazy” and “stupid” because they had returned to Mexico in the 1920s after already having migrated here. “It was something about getting land,” is all she knew. When I told her the history of the Mexican government offering land to entice Mexicans back to their patria post-Revolution and how so many saw this as an opportunity for their families, she looked at me wide-eyed. “So they were not crazy. And that story about land was true.” Her ancestors were not crazy, illogical people. They had the family in mind as they made the momentous decision to return to their homeland. They had future generations in mind. They had her in mind even though it was decades before she was born. Teaching the history of Mexican-origin people in the United States has given me the opportunity to witness many such moments. In this article, I write about how learning about the vicious, violent policies against speaking Spanish in the schools took Spanish away from generations of people who were so traumatized that they didn’t teach Spanish to their children. These children grew up often resenting their parents for having taken away the gift of being bilingual. It was a decision that made sense to our ancestors, however, who were thinking about us, the future generations. They did not want us to experience the violence they had confronted.  Mexican American school children In It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle, Mark Wolynn centers recent research that shows that a family trauma, even if it is forgotten or silenced, can live on generation after generation. These trauma manifests themselves through behaviors, depression, obsession, anxieties, and addictions. In an interview, Wolynn talks about the “ancestral alarm clock” that goes off when we hit a milestone related to the traumatic event we may not even know occurred. For decades, Indigenous scholars have written about intergenerational trauma. Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart and Dr. Eduardo Duran are pioneers in these discussions. You can view a summary by Brave Heart here.

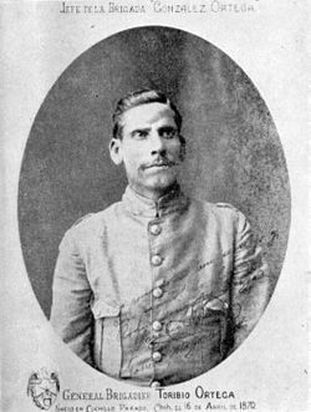

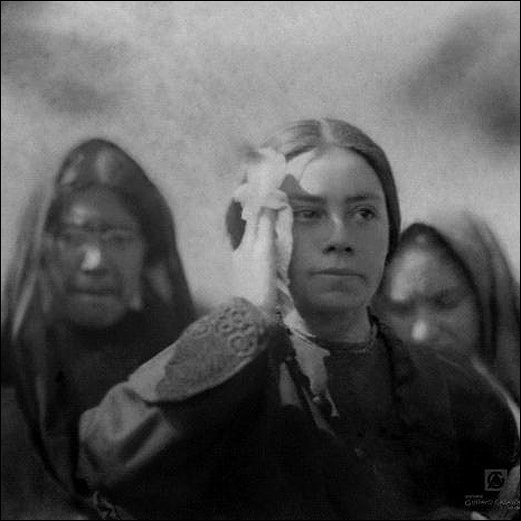

As I watched Coco, I wasn’t just thinking about Miguel, however. I was thinking about his great-great-grandmother who had been abandoned and about her daughter, Coco, and his abuelita and his parents. I thought about the dead who also needed healing. Hector, who helped Miguel navigate the land of the dead, mourned that his photo had never been placed on an ofrenda and that soon, no one would remember he ever lived. He would experience the final death, the end of memory. I believe that the dead call on us to remember them. It is not easy to heal the traumas. There are stories that we cannot speak. In my own family, I was not allowed to ask my tia abuela about my family's repatriation back to Mexico in the 1930s even as I conducted research on the million Mexican origin people who returned under duress, including hundreds of thousands of US-born children like my cousins. It would be too painful to remember, my mother told me. So I scoured newspaper articles, government reports, and the interviews of other repatriates to understand my own family's silenced history. My younger aunt, Maria Jesus, had died in Mexico City and it was a source of great grief that she had died so far from home. One year on a visit to el DF, I went to the Cathedral and paid for a mass to be said in her name. I wanted her to know that she was still remembered. Our dead want to be remembered. They need to be acknowledged and loved. Whether we know their particular traumas or not, we can learn the broader histories in which they lived and acknowledge them that way. We can pray with them and for them. We can reach out to them through meditation and reflection. We can honor them by thanking them for helping bring us to the world. We can share their stories, both the happy and the sad, and remember them that way. I cried when Coco ended because knowing that learning the true history healed the living and the dead. We, too, can heal ourselves and our ancestors and our descendants. And we don't have to wait until El Dia de los Muertos. Our dead, our ancestors, are with us always, in our DNA, in our favorite foods, in our anxieties and our character strengths. Remember them and may we all heal. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons Yesterday was el Día de la Revolución, November 20, an official patriotic Mexican holiday. The holiday commemorates the beginning of the first great revolution of the twentieth century on November 20, 1910. Years in the making, the Revolution was a response to Mexico's "modernization," which played itself out on the backs of the rural and urban poor and also resulted in the exclusion of the country's growing middle class from political power. In October of that year, wealthy Coahuila landowner Francisco I. Madero wrote El Plan de San Luis Potosí calling for the ouster of Porifio Diaz, who had ruled Mexico since 1876, as well as the installation of Madero as provisional president, and the uprising of Mexicans in revolution on November 20. The Revolution lasted for a decade; some say it never ended because its goals of justice have yet to be met. It resulted in the deaths of about a million people and the great movement of a million Mexicans to the United States. For many of us, the Revolution is our origin story, the history passed down from generation to generation about how we came to this country. In my own family, the Revolution played itself out for decades. Both my parents came to the United States as children, their families fleeing the violence of la Revolución. My father, descended from peones living in haciendas in Mexico's north, remembered the Revolution as a grand struggle for justice, a fight between the poor and the rich. He recalled witnessing battles as his family followed his Villista father from battle to battle. My mother remembered it very differently. From an educated, middle-class family in Ciudad Chihuahua, her family lost everything coming to the United States. Her memories of the Revolution were of purposeless violence that threatened her family. Her oldest sister had been almost shot one day walking home from school. The emotional debates over the meaning la Revolución flared between them throughout my growing up. In my neighborhood, too, memories and connections to the Revolution were evident. My friend's abuelita told us about a vecina who had been one of "those women" during the Revolution, perhaps even a prostitute with Pancho Villa. My next door neighbor growing up is the grandson of General Toribio Ortega, who fired the first shots of the Revolution on November 14, in Cuchillo Parado, Chihuahua when he led seventy campesinos against the government. On Sunday drives, my parents would point out places associated with Villa and his wife, Luz Corral de Villa who had been a friend of my tia abuela. La Revolución was no abstraction. It was and I think still is a living history. General Toribio Ortega courtesy of Wikimedia Commons Thinking about the Revolution and the iconic images associated with it, especially the soldaderas, always makes me think about the stories that are so often unheard. When I returned to El Paso in 2001, I remember seeing an ad in the local newspaper that incorporated both el Dia de la Revolución and Thanksgiving. The ad's border alternated soldaderas with turkeys. I still laugh when I think about it. But it also hurts me to remember the lived experiences of the girls and women and how they have been forgotten or silenced. I've been working on a manuscript about Mexican children on the border for decades now and reearching the book has led me to discover incredible, poignant, tragic oral histories. In the 1970s, El Instituto de Antropología e Historia collected oral histories, especially in the south, that were published as the multi-volume Mi pueblo durante la revolución. The Institute of Oral History at the University of Texas at El Paso, which I am grateful to direct, is also filled with these remarkable stories of the Revolution. Today, in honor of the celebration of the first great social revolution of the 20th century and in recognition of the experiences of the women who were to become our mothers, our grandmothers, and our great-grandmothers, I share these two stories from my manuscript.  Photo from the Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons Manuel Servín Massieu captured the essence of women's and girl's experiences when he affirmed that, "Para las mujeres, la bola era el miedo.” For the women, the unruly hordes of soldiers were the fear embodied. Servín recalled the enthralling stories which his elderly relative Celedonia often told him of her youth in Zacatecas during the Revolution. One day in the fall of 1916, she and several other young women were drawing water from a well when a commotion started. Soon, several of their parents appeared, "todos pálidos y asustados,” pale and scared, because Villistas were on their way to the rancho. To hide the girls, the parents made them climb down the wooden ladder which led to the interior of the well. Celedonia remembered that the well was so deep that a stone thrown into the well would take ten minutes to hit water. Afraid of falling into the dark depths of the well and afraid to leave because of the Villistas (who their elders had warned would "steal them and take them by force" or "would kill them and throw them to the side of the road"), the girls hid "con la muerte abajo y con la muerte arriba.” If they came out of the well, they could be killed. If they fell into the depths of the well while hiding, they would drown. It was indeed a case of “death below and death above.” After throwing them some shawls and a few tortillas, their parents covered the mouth of the well with boards and dirt. Such measures evidence the terror with which parents and girls viewed the coming of “la bola." (from Manuel Servín Massieu, "Las historias de los viejos," in Mi pueblo durante la revolución, vol. 1, 37.) .María Cristina Flores de Carlos, born in Gruyo, Jalisco, in 1906 became sick with fear after being threatened by a Villista. She recalled her fear at hearing shooting while hiding beneath a sack when the indistinguishable groups of revolutionaries came to town. But the most traumatic event came with the arrival of Villistas to her town: "When I was between 13 and 14 years old, well one time the Villistas gave me a great scare... because they wanted to take me with them, and one even threatened me with a pistol. He pointed at me because I wouldn't go with him. To me he looked very tall, surely because of the fear. He told me, 'I'm going to take you with me, girl...’ What horror! And I trembled, but I didn't want to show him fear, right? But I got scared and I got sick... I was in bed for about a month." For children like María Cristina, the militarization of gender roles entered her consciousness and her life, intimately and traumatically, during this encounter. Tellingly, there is no evidence of a protector in this story-- no mother or father, only the child herself. Flores de Carlos eventually saved herself by running into and hiding in the house of her father's employer. According to Flores de Carlos "I ended up so scared, I’m scared of everyone, especially at night. I'm here at night and I don't go out for anything, only by car if some emergency comes up and if they take me and watch over me. But I've been very scared since then." (María Cristina Flores de Carlos, interviewed by Oscar J. Martínez, transcript 557, 20 June 1979, Institute of Oral History, University of Texas at El Paso) Maria Arias Bernal courtesy of Wikimedia Commons Years ago, I used to conduct a "museum for a day" project with Juan Garcia, a social studies teacher at Socorro High School, east of El Paso. Students interviewed their families and neighbors and created an exhibit that we displayed in the school cafeteria for one day. I remember clearly that one student had recovered the story of one of her family members being raped during the Revolution. It was a story that was long-hidden because of the shame and trauma. Our families are filled with such tragedies, the susto and the miedo of our grandmothers buried as deep as the girls hidden in the well.

Today, I want to remember that the Revolution with its iconic images of soldaderas has another side. I want to listen to the voices of the girls and the women reaching across the decades. This week I was called something I’ve never been called—a Chupacabra historian. I’ve been called many things in my life, good and bad, but never that. In the midst of a struggle whose outcome will profoundly affect people’s lives and after more than a year of threats to a once tight-knit community, our cynical Mayor is attempting to pit people against each other in what he hopes will be a historian “throw down.” It's all smoke and mirrors, an effort to distract us from the underhanded actions of a city government intent on enriching their wealthy friends. At the invitation of the Mayor, self-labeled “grassroots historian” Fred Morales attacked my colleagues and I as “Chupacabra historians” during his presentation at City Council on November 14, 2017. He slandered us as plagiarists and in a written report to the Mayor and Council, committed libel by asserting that I coerced a resident to lie in order to stop the demolition of her home. The lies were outrageous and the incident drew immediate interest from the local media. Our usually sour faced Mayor even smirked as he said the words. Historian thrown down. You can see it in this video by Jud Burgess below. Despite our Mayor's glee at the potential "throw down" between historians, no throw down is imminent. I don't think the hashtag #HistorianThugLife exists. Sorry, Mayor. The unsuccessful manipulation by the Mayor, while momentarily irritating, resulted in something worthwhile for me personally-- it has made me reflect on the concept of "chupacabra historians." As my partner Diana says, thank those who attack you because even those attacks are lessons. Are there Chupacabra historians? Are there scholars who suck knowledge out of communities for their own benefit? Yes. Communities have every right to question institutions of higher education and the scholars who work within them. Generations of scholars have entered communities of color, taken the people's knowledge/ stories/ data/ history, used them in academic work, taken credit, and not acknowledged their sources. Or even recognized that in our barrios there are grassroots scholars and theorists whose work is based on their lived experiences. Communities have every right to demand that institutions of higher learning be accountable to them. Universities take millions of dollars of funding from donors who earn their wealth on the backs of the poor. Researchers accept government funding to invent new ways to police and control immigrant and POC communities. We can't ignore the power relations inherent in the relationship between institutions of higher education and vulnerable communities. We can't ignore the ways in which colleges and universities reinforce inequity. There are chupacabras among us who suck the life out of communities and turn it into academic publications. There is a grain of truth to the anthropologist cartoon that shows a family hiding the modern-day technology as the anthropologists approach. Academia has a long history of untrustworthy intrusions into people's lives. Where do scholars of conciencia fit? Each day I wake up and recognize that I am privileged to work with students in a community that I love. I have spent the better part of two decades mentoring students seeking graduate degrees. Like me, many of them are the first generation in their families to go to college or to seek a higher degree. I tell them about my parents who had a third and sixth grade education, who attended segregated "Mexican schools," and who supported my graduate education even though they didn't quite understand what I was doing.

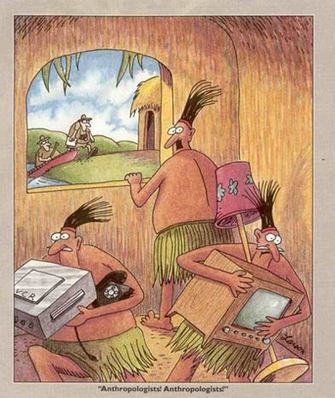

I listen when my students tell me that they don't feel like they fit in academia. Figuring out where we belong can be a lifelong pursuit. In my city, three percent of Mexican American women have a graduate degree of any kind. Less than 1% of doctoral degrees in the United States belong to Latinx scholars. I was the first Chicana to receive a PhD in History from the University of Arizona, an institution that had existed over a century at the time I graduated. The previous Chicana doctoral student had been pushed out of the program because of her radical politics. I was perhaps the thirtieth Chicana to get a PhD in history at all. We are rarities. This is not a source of pride, but for me, a source of anger that we have been excluded for so many years. My first semester in my doctoral program at the University of Arizona, a full professor known for his work in ethnic history told me to drop out. I didn't have what it took to earn a PhD. He said my people didn't have a history so there was nothing for me to study. He called fellow students in my class on the phone and told them I was not a scholar; I was simply filiopietistic. I had to look up the word. When I looked it up, it said someone who has reverence for their ancestors. That part was true. But did that mean I wasn't also scholarly? Students of color, working class students, women students often tell me they are afraid of being found out-- they fear that they are frauds, that they don't belong. The most brilliant among them feel inadequate. I understand that feeling well. I suffered from imposter syndrome even before I had heard of the term, coined by a psychologist in 1978. but let me be clear that we didn't create imposter syndrome. It serves the power structure well. If we are constantly in a state of fear and feeling like outsiders, it undermines our ability to create deep structural change. The fear is real. So is the need to find ways to nurture our own sense of confidence and belonging, both in academia and our communities. The balance between academia and community is never simple for scholars of conciencia, the contra-chupacabras. Having spent years earning our degrees in order to serve our communities as scholars, academia simply pats us on the back for our service. In academia, "service" is least valued among our three responsibilities of research, teaching, and service. For scholars of conciencia, to be of service is why we worked for our degrees. How do we navigate an educational system that reinforces inequity while working towards justice? How do we serve our communities when they may respect us as "la maestra" while perhaps viewing us as snobbish at the same time? After almost three decades in academia, I still struggle to find the balance, but I have hope. As contra-chupacabras, we nourish our communities rather than take from them. We welcome people in our community as fellow scholars who know more about their lives than we do. We ask how we can be of service to our comunidades rather than what we can take from them. We don't give voice; we listen. No historian thrown down here. My beloved granddaughter, Today, you turn 14 years old. You are a young woman. Today, I send you love and courage and strength. And many thanks for all you have taught me. I will always remember when I first met you. Your little spirit would come to me often while you were still in the womb, speaking to me during times of silence. I’m coming! I’m on my way! Your little spirit voice would announce. Then I met you in the flesh when you were seven hours old, having flown from Tucson to Portland and driven from Portland to Salem as soon as your daddy told me your mama was in labor. In the first days, we developed a relationship that was deep. You snuggled in my arms, always in the same position, and I sent you energy through my hands to help your transition into the physical world. In the years of our life together, we have walked side by side on the Red Road. While your mama was in labor with you, I made you a medicine necklace in the way I had learned from curandera Zelima Xochiquetzal, who taught me that every knot I tied in the necklace was a special prayer. I placed a piece of turquoise at the center because our people have always treasured it and I wanted you to know that I treasure you. I called you Tochtli from the beginning because you were born on the day Two Rabbit/ Ome Tochtli, connected to the moon and the maguey. Connected to healing. When I was in Mexico City at the Zócalo a few months after your birth, a danzante carved a soft stone into the image of the rabbit in the moon so that I could hold it for you until you were ready. I had always known about the rabbit in the moon because on full moon nights, my daddy/ your great-grandfather would take me to the front yard and tell me, Look mija. Look at the rabbit. Can you see it? It was an ancient vision, passed down through the generations. I keep the carved stone on my altar, waiting for the right time to gift it to you. The rabbit in the moon from the Codex Borgia. When you were three, I took you out to the desert to teach you how to harvest sage. My friend Jessica accompanied us with the love and enthusiasm she always held for our adventures in the desert and the mountains. I told you never to yank a leaf or a branch off the plantita. Ask permission, give some tobacco, and gently tug. The plantita will give you what she can. I knew that you could have a special relationship with the plantitas because you are of this desert. At three and four and five, you came to know the gobernadora, the desert sage, the fringed sage, the maguey and the nopal. At your naming ceremony at the home of your Nana Magdalena, you sang to the flowers floating in the water. When you were four, we used to stand in my front yard, the same one where my daddy had shown me the rabbit in the moon many years ealier, and we would sing to the Moon. La Moona you used to call her. Metztli, Metztli, Metztli. Metztli, Metztli, Ometeotl, we sang together. Singing has been one of the things that brings us together. Together we have learned songs for the temaskalli, the Sun Dance, the Moon Dance, the Medicine Ceremony. Your beautiful voice is one of your gifts. We have danced side by side at Sun Dance with Abuela Bea who made you a beautiful dress when you were four or five to welcome you to the dance. You have supported me through my Sun Dance, always in the arbor with your grandmother, Diana, and you have drummed and sang Sun Dance songs for the children. This year, Grandmother Diana brought you to the Moon Dance Circle in our desert where you witnessed the prayers and the women’s dance under the guidance of Abuelita Bea. You have always had the heart of a Sun Dancer. If it is your path, I would welcome you as a Moon Dancer. It is the duality inside all of us. Just as I have learned from you, I have tried to share with you the things that I have learned from the desert and the ceremonies and the Abuelxs. I have always wanted to protect you because I know that a young woman in this society is vulnerable to so much violence. I have always tried to teach you strength and help you grow your sense of self. I have wanted to encourage your tender heart. And challenge your intellect. And inspire your sense of belonging. You belong here, in this world, in this desert, in this family. Honor all your ancestors, mija. In you live all the ancestors-- from the Americas and Africa and Europe. We are blessed to live in the desert where our Indigenous abuelas and abuelos have lived for millennia, but always remember the others who came from far away by force or through need. Love every part of yourself.. In our teachings, our lives go in cycles of thirteen. You are in your second cycle of 13 years. It is a time of exploring who you are, of great emotional ups and downs, and connecting to your heart. When people dismiss young people with, Oh, they are just being teenagers, it is only because we forget what it was like to be your age. Have patience with the adults because sometimes we do forget. I know that at 14, I had a profound internal life where I thought about the meaning of life, and started to write poetry and journal, where I was inspired by movements for social change, and where I felt like the whole world was open to me. On the outside, I was moody and critical and judgmental of my parents and I felt alone, so alone and often scared of the future. Every stage of our lives has its challenges and its gifts. Embrace both as you become a young woman. Remember who you are and the road you have already walked. Remember the grandmothers who walked the road before you and how each step they took softened the ground and made way for your own pasos. I am grateful for you always because you are my teacher. I first learned how to love like an abuela from you. To love like a grandmother is distinct from loving as a mother. A mother/child bond is so strong. It is a love defined by two. In a grandchild, however, one can see the long line of descendants that follow. One's vision changes and the love grows across generations and through time and space. A grandmother's love is a love for all the children to come. It is expansive and boundless. Happy 14th birthday, Tochtli, my granddaughter, my teacher. Fenced in by the El Paso Police Department, September 12, 2017

I’m back. After a two month absence from Fierce Fronteriza, I am back, writing and reflecting on life on the border. You know the cliché life happens? It’s true. Life happened to me, all around me, and it forced me to stop and consider how to take care of myself in the midst of trauma. Just days after my last blog post in September, I found myself fenced in by the El Paso Police Department, many in riot gear, with a group of El Pasoans protecting a historic, low income, mostly immigrant, largely Mexican American community from demolition. For over a year, I have worked with the residents of Barrio Duranguito in El Paso’s southside as part of a grassroots organization, Paso del Sur. My life has centered on a small neighborhood, once known as the First Ward, whose historic and architectural significance is well-known to scholars in the area but is denied by our City Council, their staff, and their friends, the wealthy real estate developers.

Stopping the bulldozers the night of September 11, 2017. Photo courtesy of Paso del Sur.

The night of September 11, bulldozers arrived in the neighborhood and were stopped by residents and supporters. That evening, three El Paso appellate judges signed an order saying the City must stop any demolition of the neighborhood, pending the resolution of litigation in the courts. I arrived at Firemen’s Memorial Park in the barrio in time for the celebration. The next morning on my way to work, I decided to drive by the barrio to do a welfare check only to find that demolition was underway. A demolition company, hired by the property owners of much of Chihuahua Street, was conducting a drive-by demolition, causing damage to numerous buildings between 7 and 7:30 when I arrived.

First photo of the drive-by demolition. Photo courtesy of Paso del Sur.

Despite the arrival of one of the legal team, with order in hand, the men continued ramming the buildings until we called the police. The police stopped everything until they could verify the order. Soon almost a hundred supporters arrived and in the 95 degree heat, we tried our best to stop the company from putting up fences around the buildings in order to continue the demolition. I look back on my Facebook Live videos from that morning and the events of that day are almost unreal. Rather than fence the partially destroyed buildings in order to keep us safe, the police assisted the demolition company in fencing us in with the buildings. We were not allowed to leave and return. Once we passed outside the make shift gate, we had to remain outside, away from the buildings. We chose to remain inside since it was clear that the City didn’t respect the court order. This meant that we had not access to bathroom facilities, to places to sit, to food. The police allowed water in, but nothing else. At one point in the afternoon, over thirty policemen appeared in riot gear and they were intimidating. Yet, they had fenced us in. People of all ages, all genders, all physical shapes, and many of us dressed to go to work. We were anything but threatening. We heard they had planned to tear gas us. Looking back, I wondered how could they do this legally? Why would they do this? We were not breaking the law. The property owners were. The City of El Paso was. The demolition company was. We were stopping an illegal demolition, yet one City Council rep brought food for the police officers while they denied us food. Some of my friends were manhandled by the police and they still feel the physical aftereffects. Every day for exactly two weeks after this, I cried. I remember it was exactly 14 days and then I didn’t cry about it again. But what remained with me for two months was weariness, exhaustion, and a painful flair up of fibromyalgia. My neck has hurt so much since that day that I can barely turn side to side.

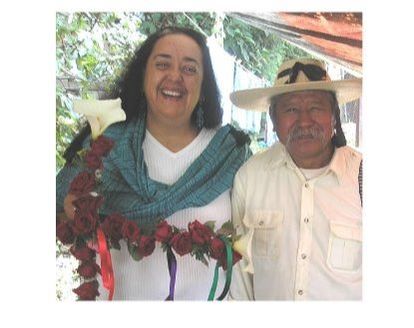

Don Aurelio, elder from Amatlan de Quetzalcoatl, 2005.

In our traditional teachings, susto is a response to a traumatic experience. We lose a part of ourselves. One of my maestras, Elena Avila, talked about how susto manifests itself physically, emotionally, and spiritually. It is a loss of part of one’s soul and it must be retrieved. I remember years ago being in the home of an elder in Amatlan de Quetzalcoatl in Morelos, Don Aurelio. He is a well-known and widely respected curandero, granicero, and community leader. One day, he showed us a jar with some dark liquid. It was one of his remedies against susto and it was made of many different poisonous insects: centipedes and spiders and other venomous creatures. Honestly, it looked horrible. Don Aurelio asked if I wanted to be treated for susto and I said I did. I didn’t particularly feel like I was suffering from susto but I knew enough to realize that we could be traumatized and not consciously know it. And I knew that I had experienced enough trauma in my life to have susto. Don Aurelio stood behind me, lifted up my hair, and put some of the venomous insect liquid on the back of my neck. I thought, I don’t feel anything. I don’t think anything is happening. When I saw the photos that my friends had taken, my eyes had rolled back in my head. Clearly, something was happening. I thought about that today, about how events leave us asustados and then the susto begins to feel normal and then, as in my case, I just live with the pain and the weariness and the feeling of exhaustion. I thought about how the susto of that day has affected me for two months and how difficult it is in this state to do something about it. The beautiful thing about community, however, is that we don’t always have to do things by ourselves and in the midst of this trauma, I have been loved and brought into ceremonia and cared for so that I can start coming back to myself. And that’s where I am- trying to come back to myself, to retrieve the part of my fierceness that was torn away from me that day, exactly two months ago today. Singing and praying and remembering myself back into wholeness, day by day. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022