|

I made a decision today about words. As a writer and historian, I know well that words hold power and that they hold history. So I'm taking the X out Xicana. I don't believe in telling others how to label themselves. We all have the right to self-identify so my decision comes specifically from my own experiences and desire to honor the history that I have lived.

I always adhered to the linguistic theory that the words Chicana and Chicano originated with the word Meshicana/ Meshicano, the Hispanicized word for residents of Meshico-Tenochtitlan. This theory posits that the sh eventually became a ch so that Meshica became Meshicano became Shicano became Chicano. The grandfather of Chicano Studies, Américo Paredes, disagrees. Remembering the first time he heard the word in the 1920s, he writes that his brother lovingly called their little niece "pura Chicanita." He goes on to write that Chicano is simply a "clipped form of mexicano." Writing that in Spanish we use the ch to denote affection, he says mexicano became Chicano as a way of creating a warm and loving term. It makes sense, actually. I do it all the time. "Preciosa" becomes "prechiosa" when I am talking to my beloved dogs. My tía abuela Concepción became Chonita. My primo Jesús became Chuy. My aunt Maria Jesus became Cachuy. We do love ch. (See The Borderlands of Culture: Américo Paredes and the Transnational Imaginary by Ramón Saldivar.) My father, born in 1910, always used the word Chicanito and Chicanita as a form of affection. In the early 1970s when, as a 14 year old, I adopted the term to identify with the political movement, it angered him because my using it had transformed it from a familiar term of endearment to a radical, political identity. Since that transformation in the 1960s, the word has always been controversial. I'm not sure when I saw the x in Xicana for the first time... probably in Ana Castillo's work. I know replacing the ch with x was made with the intention of reconnecting to our indigenous roots by incorporating the x, which folks connected to Nahuatl. I'm not the first to point this out, but the x as a ch sound isn't Nahuatl. The x as an sh sound was, in fact, 16th-century Spanish. Spanish grammarians later changed the x to denote an h sound. Thinking of it in English, Meshico (which the emphasis on the second syllable) became Mehico (with the emphasis on the first syllable). I want to acknowledge the colonial roots of using the letter x. There's something inherently colonial in using the Spanish alphabet and its archaic pronunciation to connect to an Indigenous language. Since our original languages were taken from so many of us, using Spanish is sometimes our only resort. I don't want to make the colonial invisible, though. So I'll be going back to what I've always been-- Chicana. The word connects with me with my daddy's generation who saw it as a beautiful loving term to speak of working-class Mexicanas and Mexicanos. And I'll use it to connect me to the Movimiento that so inspired me beginning fifty years ago when I was a young woman with a desire to change the world. I love that language changes and transforms to reflect new understanding and new critiques. I love when language challenges me to rethink what I know. So the x is good. I just won't be using it anymore.

0 Comments

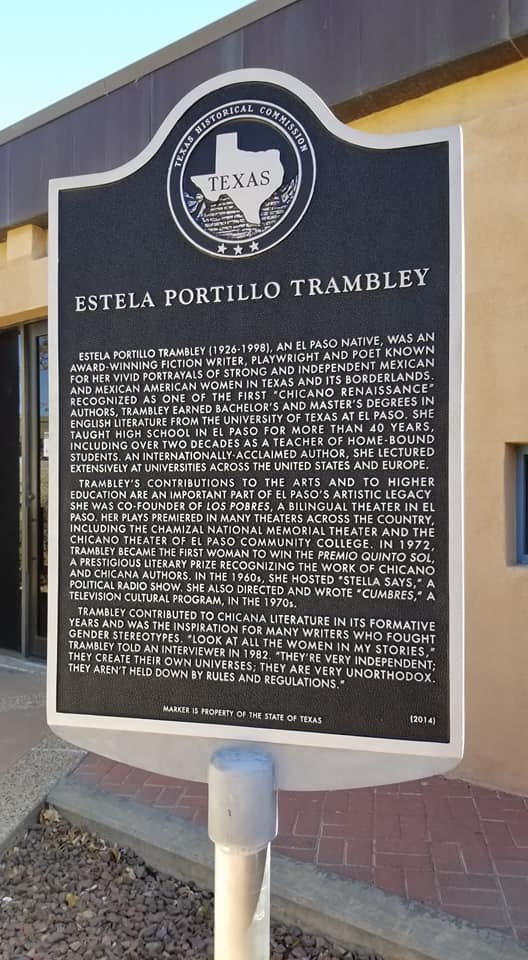

On February 24, 2018, the El Paso County Historical Commission and the National Park Service unveiled a new historical marker honoring Estela Portillo Trambley. Part of the Texas Historic Commission's Untold Stories, the marker commemorates Estela in a place that debuted many of her original plays, the Chamizal National Memorial. I was honored to say a few words about her and even more honored to say what she meant to me in the presence of her familia, Tracey A. Trambley and Bethany Trambley. I share them with you here and encourage you to read the work of this remarkable Chicana writer and maestra. Unveiling the marker at the Chamizal National Memorial. Photo by Lucia Martinez. In 1975, I was a sophomore at UTEP taking a Chicano literature course and spending a lot of time thinking about my identity and my place in the world. My professor, Dr. Teresa Melendez, assigned Day of the Swallows, a play that centers Josefa, a reclusive lesbian who lives in the traditional, patriarchal town of San Lorenzo. In later years, I read other works by maestra Portillo Trambley--Rain of Scorpions (1975), and Trini (1986). Trini explores the life of a young Tarahumara woman crossing the border from Chihuahua to the United States in the 1940s. Her work was ahead of its time as she wrote about indigeneity, single mothers, and the migration of women. Tracey Trambley, Estela's daughter, delivering an eloquent speech about her mother's writing and her love for people. To read a woman-centered Chicano play in the mid-1970s was revolutionary. In the midst of poems, novels, and short stories that told the stories of men and sometimes relegated women to one-dimensional stereotypes, Estella Portillo Trambley portrayed Mexicana women in all the complexity of our lives. I loved her work because I could see myself and my community in her words and her stories. For the first time, literature resonated with my experiences as a woman who carries the stories of generations of my family and as a fronteriza living in the beautiful and complex world of the border. Estella Portillo Trambley was the first in many ways. The first Chicana to write a book of short stories, she won the Quinto Sol Award for that book (Rain of Scorpions) in 1975. She was the first Chicana to write a musical. She founded the first Chicano theater company in El Paso and produced several original plays during her time as dramatist in residence at El Paso Community College in the mid-1970s. In 1995, she was named to the Presidential Chair in Creative Writing at the University of California, Davis. Era única, but she also represented us, the people of the border and our stories that replay themselves generation after generation. I searched for Estella in the historical records recently, looking for traces of her particular life as a fronteriza. I found her as a 4-year-old in the 1930 Federal Census, living with her mother Delfina and her father Frank. Delfina came to the US from Parral, Chihuahua in 1904 as a toddler and her father Frank migrated from Ciudad Chihuahua during the Mexican Revolution as a teenager in 1916. As the Great Depression began, they lived at 700 Park Street in El Segundo in a building long since demolished to make way for a housing project. By the late 1930s, the Portillo family had moved to what was once East El Paso to 3426 Pera Street, five blocks from my own family. While my family home was demolished to make way for US 54, the Portillo home remains. In 1943, her father Frank petitioned for citizenship followed by her mother in 1952. Delfina’s petition for naturalization reveals that she arrived in El Paso by train, that Estella was her first-born, and that she desired to keep her name Delfina Fierro Portillo. Estela’s family story mirrored my own family in so many ways: The migration from Chihuahua across the border to El Paso; Putting down roots in El Paso’s historic southside barrios; Taking the lifechanging step of becoming a US citizen. During an interview, she said, “When I was a child, poverty was a common suffering for everybody around me. A common suffering is a richness in itself.” It is that sense of the common experience, the reality of the border, that grounds her work. But it is also the sense of magic, beauty, and hope that uplifts us as readers. Photo by Lucia Martinez. The Chamizal is an ideal place for her historical marker. Several of her plays were produced here between 1974-77. In May 1977, the El Paso Herald Post reported on “Isabel and the Dancing Bear,” written by Estella for the EPCC Chicano Theater. The play featured a family who lived on Pera Street who maintained their illusions about life despite its hardships. Estella Portillo Trambley was an educator at heart, whether sharing her insights through her writing or as a teacher in the public schools, EPCC, or universities. I never met her yet I learned so much about myself from her. Rooted in her experiences en la frontera, Estella Portillo Trambley’s work also transcends the border. Her work is both fronteriza and universal as she writes about struggles and hopes, dreams and disillusionment. I am very pleased to be here with her family today to honor her. Estela Portillo Trambley carried our border stories and we are blessed to have her work still with us. Left to right: Tracey Trambley, Bethany Trambley, and the two sisters with the new marker. Photos by Lucia Martinez.

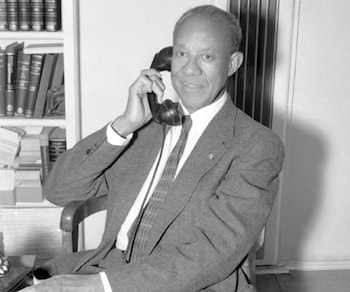

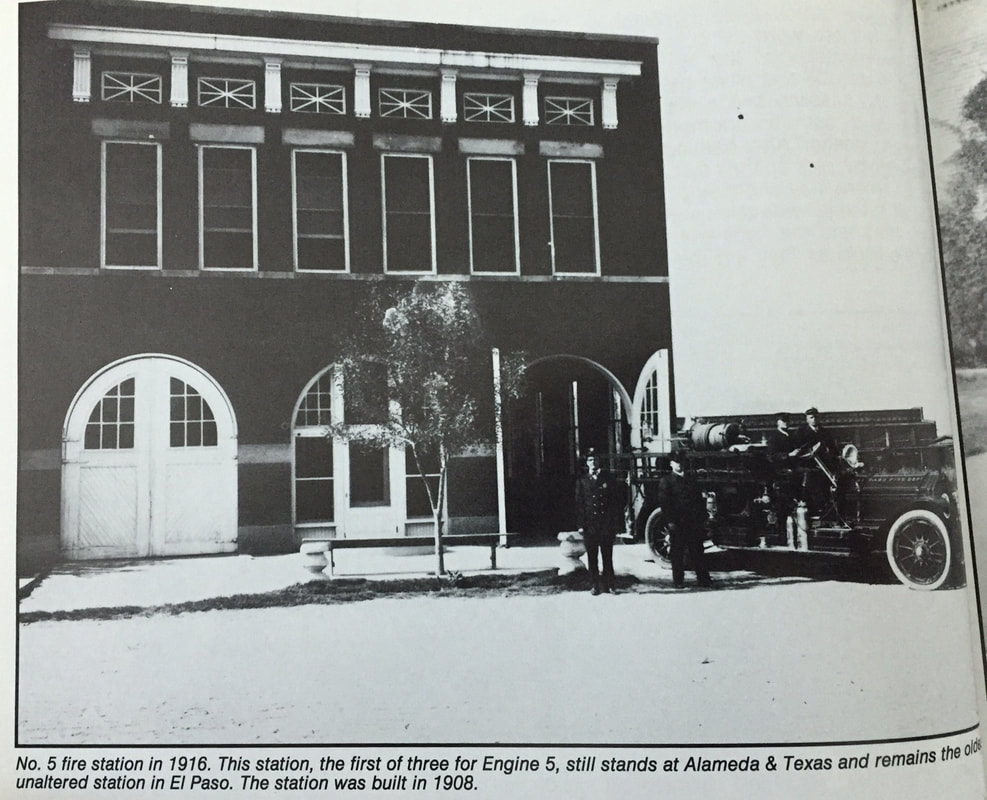

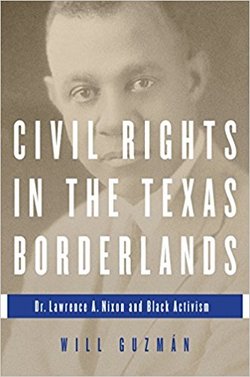

Dr. Lawrence A. Nixon On July 26, 1924, Dr. Lawrence Nixon walked into Fire Station #5 to cast his vote in the Democratic primary. When he walked up to the election officials and showed them his poll tax receipt, they denied him the right to vote. He recalled that the two election judges, C.C. Herndon and Charles Porras, were his friends. They asked about his health, and proceeded to tell him that he could not vote. "I know, but I've got to try," he answered. The two men agreed to sign a statement that had been prepared by the NAACP saying that they had denied Dr. Nixon the right to vote because he was Black. I thought about him as I voted in the primary this morning. Photograph from http://www.preservationtexas.org/endangered/east-el-paso-fire-station-no-5/ In Texas, whoever won the Democratic primary was sure to win the election. The primaries were important. In 1923, the Texas State Legislature passed a law making the Democratic primaries "white only." This law was part of decades of actions on the part of Southern states to disenfranchise Black voters, along with extra-legal violence that intended to keep African Americans away from elections following Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow. When Dr. Nixon was denied the right to vote that day in El Paso, he and the NAACP took the election officials to court. The case, Nixon v. Herndon eventually made it to the Supreme Court where the ruling stated that Texas had indeed violated the rights of African Americans under the 14th Amendment. The Court went on to add that it would be constitutional, however, for the Democratic Party (rather than the State of Texas) to declare white-only primaries because they were a private organization. Dr. Nixon went on to challenge this again when he tried to vote in 1928. It was not until the 1944 ruling in Smith v. Allwright that white primaries would be ended forever. The site where Dr. Nixon challenged his exclusion from voting in 1924 as it looks today. For much of our history in this country, we have turned to "whiteness" to claim our rights. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo offered citizenship to the 60,000 to 100,000 Mexicans incorporated into the United States through war, yet the Nationality Act, also known as the Naturalization Act of 1790 restricted citizenship to "any alien, being a free white person." This was a conundrum for Mexican Americans. The 1887 case re Rodriguez stated that because the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo made us eligible for citizenship, we must be white. We were not treated as "white," facing segregation and myriad kinds of economic and social discrimination yet we had to claim to be white in order to be citizens. While Blacks were excluded by law, we were segregated by practice. There were "Mexican wages" and "Mexican schools." When the local El Paso bureaucracy tried to classify Mexican American births as "colored," there was great opposition from LULAC and other Mexican Americans. As "whites," we were not excluded from voting in the Democratic primary and, in fact, El Paso's Democratic Ring relied on the Mexican vote in the first decades of the twentieth century. When Charles Porras denied Dr. Nixon the ballot that day, he was reinforcing his own sense of whiteness. Porras was a World War I veteran, a local LULAC leader, and went on to organize laundry workers and domestic workers into a kind of union in 1933. When he ruffled the feathers of El Paso's powerful by doing this, they asked for his deportation. There was only one problem: he was born in New Mexico. When Dr. Nixon walked into Firehouse #5 that day in July 1924, he was challenging the exclusion of Blacks from the political process in Texas. But he was also challenging Mexican Americans to take a side. Would we claim whiteness (in opposition to Blackness) in order to claim some kind of rights? For decades to come, that would be the case.  For more information on Dr. Nixon, I recommend this book by Dr. Will Guzman, a graduate of UTEP's History Department. Some people are the carriers of their family's stories. Some people don't care and would rather forget the past. In March, Fiercefronteriza will present a series of blog posts on why family stories matter. Let me know-- do they matter to you? Why or why not?

I am not a visual person. I often don't notice detail. I don't have a sense of space. In my fifties, for the first time I noticed that light changes subtly during the day-- and someone had to point it out to me.. A couple of years ago, I decided that it was time I developed my eye. Instead of seeing just the broad strokes of what was around me, I wanted to understand how to really discern what surrounded me. So I began to study the works of artists who inspire me and whose work evokes emotions and ideas and memories. I didn't study in an academic sense but in the sense of sitting with an image, noticing the details, the colors, the angle and the relationship of these to each other. I try to sit still and listen to the feelings and thoughts the photo evokes. When I decided to learn to see, I chose fronterizas and fronterizos-- photographers and artists-- who I knew could teach me because we share both the beauty and the difficulty of living on the border. They embrace the contradictions of living on the margins and the center at the same time.

Federico Villalba is one of my teachers and I have never told him. An art photographer/ street photographer from El Paso, he said in a 2016 article that "it is not [his] intention to photograph an image that does not genuinely exist, nor alter it into an illusion that it is not." That is one of the aspects of his work that resonates with me. Here on the border we don't have to alter reality-- it is already remarkable. People who come here either love it or hate it. People who grew up here try to leave but we usually come back. If you love the border, you can see the astonishing place that it is. If you love the border like Federico does, you find a way to document it. Federico's photographs are evidence of his love for la frontera, the people, the buildings, the relationships, the history, and the culture. Whether it is a photo of matachines dancing in front of a mural of la Virgen de Guadalupe or a poignant image of an elderly couple sitting on a bench, his photos bear witness to this constantly changing place where the ancient and the modern live side by side. Each time I hear that he is exhibiting his work (and he has exhibited widely), I am happy because others will see his vision of the border. It was difficult to chose the photographs for this post. There are so many. So I decided to post those that spoke to me today. Every time I look at Feredico's IG account, I see new photos that speak to me. The captions below are Federico's; I've added some comments throughout in maroon font. Please note that all photographs are ®Federico Villalba, All Rights Reserved. Federico, thank you for your work and for being an inspiring and generous maestro.

The border is full of movimiento and life. On December 12 of each year-- the day of Our Lady of Guadalupe-- matachines, dancers devoted to her and to the Catholic Church, move in ancient patterns that remind us our culture existed for millennia before European contact. The ancient dance illuminated by neon lights- that is la frontera.

Durangito OCT2015. Save the neighborhood, save part of the history of El Paso, Texas. Photo: ®Federico Villalba, All Rights Reserved.

The couple sitting on this bench, facing their home, had lived here for many years at the time Federico took their photo. Each afternoon, they sat outside talking, often accompanied by their neighbors. During the summer of 2017, the couple were forced to move by their landlord because he intended to sell the building to the City so they could build an arena. On September 12, 2017 the City of El Paso allowed the property owner to demolish a portion of the building despite an existing court order saying no demolition could take place. A few days after the illegal demolition, she returned to the neighborhood to see her home. She said it would "always" be her home.

Procession of newsprint and wheat paste superheroes in South Central El Paso, Texas. Crazy for El Loco. Photo: ®Federico Villalba, All Rights Reserved.

What can I say: on the border, we are always on the move!

Comida Corrida $5.49 @ Sr. Benjos: Ringside to life on Alameda Ave. Photo: ®Federico Villalba, All Rights Reserved.

Alameda runs from southeast central El Paso to the Lower Valley. Once lined by álamos (cottonwood trees), the street cuts through what used to be east El Paso, a Mexican barrio that grew along the river at the turn of the 20th century.

Clay, mortar, and steel. Memories of El Paso's past fading into ruble. Photo: ®Federico Villalba, All Rights Reserved.

In 2016, this 107-year-old former flour mill was demolished to make way for a new highway. Federico's photo brings me comfort in its absence. Driving down I !0, I always felt connected to our city's history when I saw this old building, a reflection of El Paso's early urbanization..

Photo: ®Federico Villalba, All Rights Reserved.

In September 2014, 42 students from a rural teachers school in Guerrero, Mexico were kidnapped. They are still missing. El Pasoans held a vigil to call for their return. Activists and families on both sides of the border continue to demand their return.

Posada at historic Barrio Duranguito, Dec. 20, 2017. Photo: ®Federico Villalba, All Rights Reserved.

Federico has been a steady presence in Barrio Duranguito for the past year and a half as residents and supporters fight for the survival of this historic neighborhood. The posada, the re-enactment of Mary and Joseph seeking shelter, is a particularly potent symbol in the barrio since people began to be forcibly displaced from their homes last year.

You can follow Federico Villalba on Instagram here:chancla_rodriguez or on Facebook here: federico.villalba.1804.

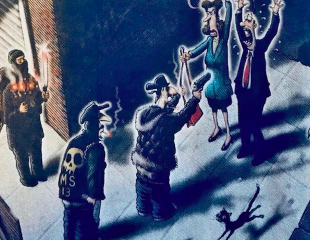

Photo courtesy of Cynthia T. Renteria Yesterday I stood at the border fence that divides El Paso, Texas from Ciudad Juárez watching the birds glide back and forth above it, drawn to the puddles of water in what once a raging Rio Bravo/Rio Grande. Against the backdrop of the desert sunset, they looked graceful as they flew effortlessly between the United States and Mexico, transcending the ugly man-made fence. The fence was built here in 2008 under the Obama administration. The Democrats agreed to build a taller border fence because the Republicans agreed to consider broader immigration reforms if the administration agreed to stricter border enforcement.... so the ugly fence was built between our cities that have been one community in myriad ways for most of our history. Our economies are tied together. Our culture. We have family members on both sides. My former student, Gus, used to tell me that when the fence was being built, it sounded like it was crying as the desert winds blew through it. I've always remembered that image of the fence crying. Our current mayor, our local Trumpish millionaire, calls it a "freedom fence" and talks about immigrants as riff-raff. These were my thoughts yesterday as Movimiento Cosecha and their supporters gathered to talk about the 11 million migrants in the United States without status in this country. As the border action got underway, with the backdrop of the fence and a Border Patrol car parked watching the river behind it, we heard the testimonies of the organizers who volunteer full-time to work for respect, dignity, and permanent protection for the millions of migrants living in the United States. The oldest organizer is 25. It is a movement led by young people fighting not just for themselves but for their parents, the original dreamers who came to this country with hopes for a better life. They fight for the 11 million who work in the fields, in construction, in meat packing, and kitchens.  The demand for respect and dignity was highlighted this week when The Albuquerque Journal published this racist cartoon portraying Dreamers as criminals. Under national public pressure they issued an apology. Movimiento Cosecha emerged in 2015, choosing the word "Cosecha" (harvest) to honor "the long tradition of farmworker organizing and the present-day pain of the thousands of undocumented workers whose labor continues to feed the country." The Movimiento is non-violent and uses non-cooperation "to leverage the power of immigrant labor and consumption and force a meaningful shift in public opinion." You can read more about them here. The testimonies yesterday included the story of Jose Luis and his family, Zapotecos from Oaxaca who migrated to Florida. The migration of Indigenous people has been growing in recent years but it is a movement of people across this continent that predates the fence and the border by millennia. We heard from Nancy whose family came from Chihuahua. We heard from Cat who grew up in New Jersey. Others shared their stories. Supporters included artists, community organizers, professors, students, and other community members who support the work of Movimiento Cosecha because we all want a more just nation and a more just world. Mid-way through the action, organizers clipped three huge banners to the border fence. "Dream without walls-- Aquí los sueños no conocen fronteras" the message announced. I thought about my family who crossed the border without papers in 1914 and their dreams of finding work and a peaceful life. I thought about the Mr. Avila, a former Bracero who I interviewed recently. Now in his 80s, he talked about coming to the US, suffering as he worked under harsh conditions in the fields but the hopes he held for his family. "Me, I can be anywhere. But my family, here," he told me. Through their fearlessness in the face of ever-growing threats, despite the efforts of politicians to use them as bargaining chips, and in spite of the racist rhetoric that has found a safe place within our country since the election of Trump, Movimiento Cosecha and the mostly young organizers nourish those dreams. Respect. Dignity, Permanent protection. If you would like to support Movimiento Cosecha, go here.  Photo courtesy of J.E. Meyers Last night, Professor Emerita Angela Y. Davis spoke to an overflow crowd at the University of Texas at El Paso. Her hour and a half presentation, organized by Dr. Michael V. Williams, Director of African American Studies, was thought-provoking, engaging, humorous, and profound. As I took notes on my cell phone, I thought of the many blog posts that could come from her comments. I woke up thinking about one thing she said, however: Universality can come from below. Dr. Davis spoke of the ways in which white and male are seen as universal and recalled challenge to this by the groundbreaking 1982 book, All Women are White and All Blacks are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave. Before we knew the word "intersectionality," we lived it, as women, as lesbians, as people of color, as poor people, as immigrants. I remember in the 1970s carrying a sign at a gay pride march in Austin where I had written simply "We are not all white." I doubt many of the participants paid much attention to my homemade statement but as a 20 year-old trying to figure out how to not just live but politically organize a life of intersectionality, it was something I felt I had to state. We are not all white. What Professor Davis said last night challenges us to take it even further than the "We are not all fill in the blank" of my youth. To understand that universality can come from below is to understand who we are rather than who we are not. To understand that universality can come from below is to uncover the connections among us that link us across our limited identities of members of nation-states and that transcend borders. To know that universality can come from below is to see ourselves in others. It is to honor our ancestors and to take all actions with the generations to come in mind. I would love to hear your thoughts on universality from below. What do you think? Do you have examples? Does the concept of universality benefit us? I hope to hear from you! 2000 people went to hear Angela Davis at UTEP. This is the crowd waiting for her to appear an hour before the talk.

|

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022