|

Recently, I read an article about Jedidiah Brown, a 30 year old pastor and community organizer in Chicago. If you Google his name, you find articles about his work with youth, how he stormed the stage in 2016 at a Trump rally, how he served as President of the Young Leaders Alliance, and was former candidate for alderman for the 5th ward. He is a beloved leader in his community, fearless, outspoken, and eloquent. A year ago, he made the news for something else, however. On Facebook Live, he threatened to commit suicide. He reportedly said, “I’ve always loved this city and I love my family — I love everybody and I’m so sorry, but it’s over, I can’t recover from this.” He later said that the death of a family member had triggered the suicide attempt, but it is clear that his all-out dedication to the community also played a role. “Every relationship I had, I lost it because I was too busy fighting for y’all,” he cried into his FB Live feed. Brown was part of a growing group of predominantly younger activists who took on the problems of their communities, who took the struggle to heart and into their lives. In an article on Brown that appeared in HuffPost, writer Ben Austen writes that, "Many of these activists were unprepared for the emotional anguish, the self-recrimination and financial burden, the media spotlight, the attacks from outside and within the movement." I have seen the toll that activism has taken on younger activists as well as older activists. I see working people put their money and time and energy and their hearts into fighting for justice while the wealthy take vacations and hire employees to do the dirty work for them. The imbalance is undeniable; its effects are physical, emotional, spiritual, and intellectual depletion for activists. Sometimes our wounds as marginalized people under attack fester and we don't take care of ourselves because we are taking care of everyone. It is overwhelming.

We begin to attack each other, to hold each other to unrealistic standards, to act in judgmental ways. I know because I have seen others turn to these responses and I, too, have fallen into this abyss of the anguish of activism. It can tear apart movements from the inside. What can we do? After so many years, I don't have the answer except I do know that is has to do with love and compassion. It has to do with acknowledging each other's humanity, with our failings and contradictions. i know it has to do with gratitude. And acknowledging that we do what we can. A couple of months ago, Omar Garcia, a young indigenous activist who survived the horror of Ayotzinapa, visited my city. He said one of lessons that he had learned since the kidnapping of 42 of his classmates in 2014 in Guerrero was to be grateful for whatever help someone offered. If someone works and can give a hour of her time every week, that is good. She is giving all she can. In our desperation to do our community work, sometimes we criticize her for not doing enough. There are folks talking about compassionate activism now, which gives me hope. Compassionate Activism is a website with a free webinar on healing marginalization through love and justice. There is a wonderful blog post here that lists "10 Key Points for becoming a Compassionate Activist." One of the points states that "Compassion is rooted in an understanding of the connection between all living beings." It is a concept that I have long understood and practiced in my spirituality, yet somehow it has not been forefront in my politics. Love, justice, compassion, anguish, pain, despair- they swirl around in activist circles. For me, it's time to untangle them and to learn how to bring compassion into activism in my own life.  Traditional Mexican foods by Project Chicomecoatl. Photo by Mercy Salazar.  What makes Intangible Cultural Heritage significant to Chicanxs in the 21st century? Our community needs to preserve our culture for our own well-being. According to UNESCO, ICH contributes to food security, maintains good health, sustains livelihoods, respects a sustainable environment, resolves disputes, and strengthens social cohesion. As researchers explore what they label “the Latino paradox,” a somewhat controversial theory that Latino immigrants have lower mortality rates and better mental health than non-Hispanic whites, despite poverty and fewer economic opportunities. We need to look at what our culture can teach us, and others. At a time when Mexican and Mexican American culture is under attack, often under the guise of controlling immigration, we need to know that our culture has something to offer. In El Paso, a city with an 80% majority Mexican American population, resistance to Mexican American cultural preservation among the “keepers of history” is still strong. Our city tells its history as a story of Spanish conquistadores and cowboys. In 2007, the City of El Paso unveiled the largest equestrian statue in the world, a statue depicting "the last conquistador," Juan de Oñate who passed through what is now El Paso in 1598. Supporters, both Euroamerican and Latino argued that it was about time that the city highlighted Latino history. Opponents argued that spending $2 million dollars (40% came the City) on a monument to genocide and Spanish colonization was a travesty. During recent debates over the creation of a Hispanic Cultural Center, funded by a quality of life bond sale approved by voters in 2012, the chair of the El Paso Historical Commission opposed the designation of the center as Hispanic or Mexican American because the city’s cowboy culture and gunslingers should be highlighted. When the Historical Commission recently developed a plan to create a historical district that included El Segundo Barrio, they did not consult with anyone from the barrio, asking instead for a blessing of barrio leaders after the fact. I am the director and cofounder (with Dr. David Romo) of Museo Urbano, an award-winning public history project of the Department of History at UTEP. We are a museum without walls focused on reclaiming, preserving, and interpreting the history of the borderlands. Through our work, which involves everything from museum exhibits and historical booklets to community dialogue and pachangas, we invite people to think critically about history, their place in history, and to act. What I have learned over the past decade of working with Museo Urbano, both in its grassroots form and at the university, is that cultural preservation without action, history without social justice, has a hollow ring to it. Museo Urbano started on the streets of El Segundo Barrio in El Paso, Texas, grounded in the values of respect, reciprocity, responsibility, and social justice. We emerged in 2006 as part of a grassroots struggle against a wealthy group of real estate developers, who with the backing of the City of El Paso, planned to demolish one of the most historic Mexican immigrant neighborhoods in the United States—the Second Ward, the Ellis Island of the Mexican diaspora. It was in El Segundo Barrio that hugs the US-Mexico border, where Spanish is heard more often than English, where half the residents are immigrants, where 60% of the people live below the poverty level and 42% live below half the poverty line that we learned most poignantly about Latino heritage preservation and its meaning to our community. It began with two questions asked over and over “Why do you care about this barrio?” and 'What’s so important about this barrio?” Once when David Romo and I were leading a group of our students on a walking tour of S. Oregon Street, in the heart of the barrio, we stopped in front of the Pablo Baray apartments, telling the group that the run-down two story tenement had once housed a number of literary presses and Spanish language newspapers. We told them it was there that Mariano Azuela wrote and published the first great novel of the Mexican Revolution, Los de Abajo. A man who had stopped to listen asked somewhat incredulously, “Can anyone live there now? Why doesn’t anyone know about this?” He couldn’t believe that such an important historical place stood unknown and unnoticed in the middle of his neighborhood. As we researched that one street, building by building, learning the stories of Mexican revolutionaries and refugees from the Cristero Rebellion, of Don Tosti (Edmundo Tostado) the first Latino musician to sell a million albums with his song “Pachuco Boogie” in the 1940s, the African American jazz musicians who in the 1950s and ‘60s performed in small night clubs to a mostly Mexican American audience, to the great Chicano poet Lalo Delgado, author of “Stupid America,” and the Chinese immigrants who lived on the periphery of the barrio, we saw that this one street was connected to the nation and the world. We understood that this history was the patrimony of two nations. One the border, stories always transcend the political dividing line. Like Kuatemok, the last great leader of the Mexica who during the Spanish occupation of central Mexico in the 1520s urged his traumatized people to “hide all that our heart loves, that which is our great treasure,” until “our new sun rises,” our abuelas and abuelos have often kept their stories and their histories held close to their hearts. The time has come to teach our youth and to allow ourselves to remember, to bloom with the histories that we hold in our memories, in our bodies, in our language, in our food, and in the urban streets of our city. The time has come to enact Kuatemok’s great desire that his people would never “forget to guide your young ones/ teach your children/while you live/how good it has been and will be.” In the midst of war, disease, and death, the children were not forgotten. Then, as today, youth are our hope, the dreams of our ancestors. We have an obligation to remember and to protect the tangible and intangible cultural heritage of the borderlands as a gift to future generations from past generations. To begin this work, we must answer: What does cultural preservation mean along the border? What do we do now? Pachucos Suaves, mural by David Flores, 2010. Painted over by property owner now.

Today, I share with you a talk I gave in 2015 at the Wise Latina International Conference in El Paso, Texas. It began with a poem. Pat Mora is one of my favorite poets. Her poems resonate with me, rising up from this desert where both of us were born and raised. Mora begins her poem "Desert Women" with the words: "Desert women know about survival." Likening us to cactus whose skins thickens with the heat and cold, she ends her poem by saying, "When we bloom, we stun." Desert people are like the desert plants: beautiful survivors. We are a borderlands people who, like the cactus in Pat Mora’s poem, have sprouted roots into the rocky limestone soil of the Chihuahuan Desert. We have lived here, along the ancient river, among these 60 million year old mountains, sometimes for generations and sometimes for millennia. Like the cactus that during the sporadic desert rains saves each drop of water in its thick flesh, “we’ve learned to hoard” our stories, our memories, our histories “safe behind our thorns” of silence and forgetting. These thorns have protected us over centuries of attacks upon our culture, our languages, and our very worth as human beings. We don’t talk in order to protect our children from our painful experiences. We don’t speak in order to protect ourselves from remembering. The silence has protected us it, yet has left us disconnected from the generations before us, their tragedies and their triumphs, and made it difficult to see our connections to each other across and within generations. Once, remembering the suffering of the women in my own line who lived through being robadas, raped, abandoned, segregated, and who had lost children because of intense poverty, even I, a historian, wondered whether all stories deserved to live. The thorns of history, the ways in which we protect ourselves from what scholar Amy Lonetree calls “the hard truths of colonization,” are symptomatic of how we deal with historical trauma. As scholars and practitioners in social work, mental health, and psychology continue to develop the concept of historical trauma, the far-reaching ways that the experiences of our ancestors shape our psychological, emotional, and spiritual selves, scientists are increasingly understanding that the environment of our grandparents, including their physical environment, have transgenerational effects on our own health. Our histories are not dead. They live in our bodies and in our spirits. Our familial histories, both told and untold, hold power in our lives. In my classroom, students often tell me that they are shocked and surprised when their grandparents tell them what they have suffered because “they don’t like to talk about it.” In a recent class on Mexican American history, I asked students if they knew anyone who had been part of the Bracero Program, the guest worker program of the 1940s to 1960s. They all nodded “no” and we proceeded to watch “Harvest of Loneliness,” a documentary highlighting the often tragic stories of the men and women who suffered humiliation, exploitation of their labor, and the disruption of their families as a result of the agricultural labor program. As I looked out at the class afterwards, they were quiet, their eyes wide open staring back at me. I was in tears witnessing the testimony of former Braceros I had frequently seen in my work with the Centro de Trabajadores Agrícolas Fronterizos. During the break, one of the students texted her mother and discovered that her grandfather had arrived here as a Bracero. She was stunned that he had gone through the experiences portrayed in the film. A decade ago, as I sat on the steps of a modern-day pyramid building covered with beautifully painted Mesoamerican images on the campus of Universidad Nahuatl in Ocotepec, Morelos, my student Juan asked me a question that made me smile but that I have never forgotten. “Dr. Leyva, do you want us to be Aztecs?” We had gone as part of a university study abroad class to investigate indigenous stories, foods, philosophy, and history. I smiled, telling him that I didn’t want us to “be Aztecs” but that I wanted us to find ways to incorporate our ancestral Mexican culture into our modern-days lives as 21st century Mexican-origin people. We still ate our ancestral foods—corn, beans, squash, and chile. We still used indigenous words to describe our world, even when speaking “Spanish.” I knew that Mexican American Catholicism was replete with indigenous symbols and ceremonies, despite more than a century of criticism and even suppression by the U.S. Catholic Church. What had we preserved culturally, why had it survived, and how did it serve us, whether we were conscious of its presence or not? In the face of hundreds of years of cultural suppression under the Spanish colonial system and more than a century of the American educational system’s attempts to Americanize our children through policies that included corporal punishment for speaking Spanish, a disdain of Mexican culture as inferior or backwards, and the invisibility of our own history in the classroom, textbooks, and in the faces of teachers and administrators, our cultural heritage remains with us in the day-to-day ways we live. Although we have rarely had the money or the political power to protect our tangible culture, the landscapes, the buildings, the places that hold meaning to our history, we are increasingly organizing to do so. In the past fifty years, cultural preservation has taken on global significance. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) has been an international leader in supporting communities in preserving our cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible. According to UNESCO, tangible cultural heritage, the buildings, artifacts, and significant places “validates memories,” “demonstrates recognition of the necessity of the past and of the things that tell its story,” and provides people “a literal way of touching the past.” [1] Intangible Cultural Heritage, which they define as “the practices, representations, expressions, as well as the knowledge and skills (including instruments, objects, artefacts, cultural spaces), that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage.”[2] With a history rooted in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966, and UNESCO’s 1989 Recommendation on the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore, among others, UNESCO adopted the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003. [1] Accessed at http://www.unesco.org/new/en/cairo/culture/tangible-cultural-heritage/ on June 2, 2015 [2] Accessed at http://www.unesco.org/services/documentation/archives/multimedia/?id_page=13&PHPSESSID=cdf1c1b605ebc498950fa399d2ed8658 on June 2, 2015. To be continued.... At the Golden Globe Awards last night, Oprah Winfrey evoked the name of Recy Taylor who was abducted and raped by six white men as she walked home from church one night in 1944. She was 24 years old, a mother and wife, and living in Abbeville, Alabama. The men were never prosecuted. Ms. Taylor and her family were harassed by her rapists and were forced to leave their home. The case received widespread coverage in the African American press and helped invigorate the civil rights movement. In her speech, Oprah said, "She lived as we have all lived, too many years in a culture broken by brutally powerful men. For too long, women have not been heard or believed if they dare speak truth to the power of those men. But their time is up.

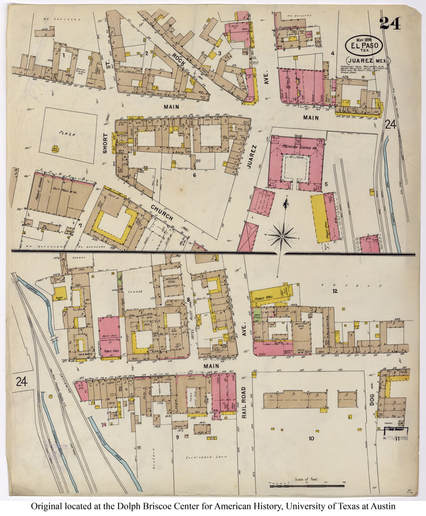

The moving speech ended with the hope that a new day is dawning "when nobody ever has to say, “Me too” again." How do we heal the generations of women past who in 2018 might be able to come forward to say #MeToo but who could not say it in 1960 or 1940 or 1900? I believe these traumas are passed on from generation to generation. As I've written elsewhere, we carry these traumas in our bodies from generation to generation. Telling their stories is part of their/our healing. In that spirit, I share the story of Mary (not her real name), an African American woman I met in the 1980s when I was in my twenties. When we met, she was recently released from prison. She had been incarcerated since she was a teenager for killing the white man who raped her. By the time she was released, she was in her sixties. For a Black teenaged girl to kill a white man in 1940s East Texas, Jim Crow Texas, there was little hope for another outcome. She came of age in prison, grew into womanhood, middle age and eventually into her old age incarcerated. She never had the opportunity to learn how to make her own decisions, to live independently, to learn about the world. Yet, she was funny and kind and talkative. As a young woman, I couldn't imagine how Mary had survived. And in many ways, she didn't. She couldn't figure out how to be in the world. She couldn't stay in her boarding house-- it was too claustrophobic. The last I knew of her, she was homeless, living in an East Austin park, accompanied by a pack of dogs that protected her. Even in the cold months, she would say she was happy there. She needed lots of space. When I moved back to El Paso in late 1986, I lost track of her. I've never stopped thinking about her, though. Now I am Mary's age when we first met and as I begin the process of looking back over my life, evaluating the good and the bad, what I've done well and how I've make mistakes, I think even more about her and wonder what became of her. There are countless Mary's in our lives. Some are in our familias. Others, like Mary, cross our paths briefly. I, too, hope for a day when no one will have to say #MeToo. Today, I remember Mary and all the other women whose stories we carry in our bodies and ask that we #TellHerStory. Recently, I've spent time in Northern New Mexico where deep history resides in the countless adobe buildings that fill the landscape. In San Miguel County, along the Pecos River, the earth is deep red and so are the bricks made from that earth. There are homes that date back to when the area was still part of Mexico where families continue to live. The two-feet-deep walls hold the warmth in winter and the coolness in summer. It is a building material that is efficient and beautiful and has been used worldwide for thousands of years. Some linguists believe that the word adobe itself is at least 4,000 years old, with roots in the Egyptian word for brick that was passed on as the Arabic word al-tob. It is a beautiful thing to be in a place where the relationship between humans and earth is so intimate. In cities like El Paso, this relationship was disrupted with the coming of "Americanos" that resulted in the destruction of traditional adobe buildings and their replacement with brick. You can see this process in the Sanborn's Insurance Maps, maps that documented the built environment in thousands of US cities beginning in the 1860s. The 1898 map below of a section of El Paso shows the brick buildings in red and the adobe buildings in brown. Over the decades, the maps reveal the red overwhelming the brown. Adobe, made of earth, was viewed by Euroamericans as a sign of backwardness, of dirtiness. In his 1920 publication, Essentials of Americanization, sociologist Emory Boggardus writes that in Mexico "the poor are living in conditions of squalor and ignorance. They live in adobe, or clay houses, with thatched roofs, dirt floors, and frequently in single rooms. It is this class which is being brought into the United States as immigrant labor." The modernization of Southwestern cities meant to government officials, scholars, and reformers that our relationship with the earth must end. You can still find a few adobe buildings in the Southside barrios of El Paso as evidenced by the 1970s photo below by Danny Lyon. In places like San Miguel County, the relationship between people and earth continues, although trailers and mobile homes are replacing many of the older familial homes. Still, the people know that without humans, the adobe loses its purpose and returns to the earth. If an adobe home is lived in and loved, however, the walls retain the heat from the wood stoves and with its relationship with people, it can live for hundreds of years. In a previous post, I asked "What happens when a building dies?" (You can read it here.) Now, I can ask, "How do we live with the earth?," thankful for the people who have kept the relationship alive between humans and the earth. Left: adobe building in San Juan, NM. Right; Adobe buildings in the Second Ward (El Segundo Barrio), El Paso. Photo by Danny Lyon as part of DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency's Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, compiled 1972 - 1977. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

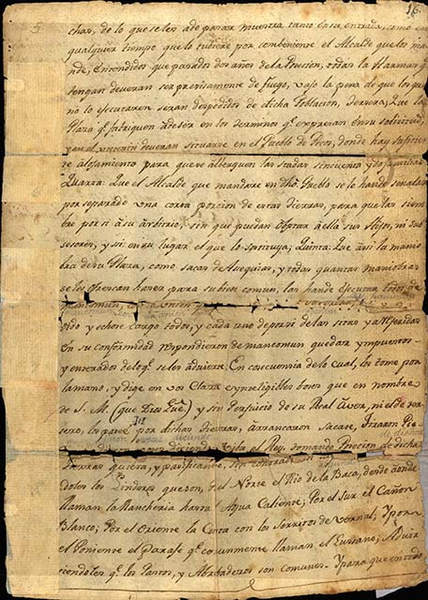

Adobe building across from San Miguel Catholic Church Winter is slow-coming to San Miguel this year. The nights and early mornings are chilly, making the warmth of the wood stove welcomed. A few days this week, the icy winds blew hard. But the mountains have no snow this year and the people of the valley are afraid of wildfires and depleted water supplies for their wells with no spring melting snow. The 900 mile long Pecos River that flows from New Mexico to Texas is already low. The mountains are filled with juniper and cedar, darker green in the winter than in the spring, and the silhouettes of gray and white leafless trees. The evergreens are stark next to the dark red soil of the valley. In the 17th century, the area was a borderlands between the encroaching Spanish empire and the Indigenous settlements that existed there for thousands of years. The settlements of this valley, San Miguel, San Jose, San Juan, Villanueva, Sena, and Ribera, are two centuries old. Some like El Barranco exist mostly on land titles and few remember their names. I wonder if the people who have lived in the valley for generations remember their history. In this part of New Mexico, it would be difficult to forget. One piece of land may hold the homes of several generations: a more modern mobile home next to an older adobe home, next to the crumbling remains of an ancient adobe house dating back 150 or 200 years. Everywhere, the disintegrating adobe homes call on us to remember the hard-working people who built them in this beautiful but isolated place. San Miguel del Vado Grant, Spanish Archives of New Mexico, Series 1. Surveyor General Records . From: http://dev.newmexicohistory.org/filedetails.php?fileID=9998. The history of this valley is a microcosm of centuries of colonization and nation-building, from Spanish settlement of the northern frontier of New Spain to the US takeover of northern Mexico in the mid-19th century. It is the story of hope for the future, loss, and resistance. When Spanish explorers first arrived to the area in the 1530s, they encountered people who they would call the Pecos, an indigenous group with roots going back millennia in the area. Puebloan culturally, they were an agricultural people who grew corn, beans, and squash and built home of adobe and rocks. Their settlements included home and kivas, underground places of great spiritual significance. Each kiva had a hole in the center representing the underworld from where the people had emerged. For unknown reasons, by around 1450 many of the Pecos settlements had been abandoned, consolidated into one. It was this ancient, thriving culture that first encountered Spaniards looking for the city of gold, Cibola. Left: San Miguel del Vado (1846) Facing toward the west, from the Report of J. W. Albert of his Examination of New Mexico in the Years 1846-1847 Right: San Miguel Catholic Church (2017) In 1794, the governor of Nuevo Mexico approved a petition by Lorenzo Marquez and 51 others living in Santa Fe who asked for land in order to provide for their families. Santa Fe, they said, had scarce water. According to the petitioner, 13 of the 52 families were Indian, probably Pecos, and historian Malcolm Elbright argues that the majority of the families were genízaros or mestizos. Genízaros were Indigenous people, often captives, who were enslaved or employed as servants. Some were given land, as in the case of San Miguel. Some retained connections with their people; others were completely cut off. They were an important part of the settlement of San Miguel and the surrounding communities. The San Miguel del Bado land grant was the first significant communal land grant in the northern borderlands of New Mexico. (Bado or vado refers to a place where the river can be forged. The two spellings are used interchangeably although Bado is the more common.) When land was finally distributed in 1803, the governor required that each household possess arms and ammunition within two years. The petitioners offered to build a well-fortified plaza for their protection. Attacks by Apaches and Comanches were foremost in their minds. For the original settlers, access to land was key to the survival of their families. The communal nature of the land grant meant that everyone would share grazing and agricultural land. For the Spanish government, a communal land grant would act as a buffer between the Comanches and Apaches and the Villa de Santa Fe. Old adobe building, Village of San Juan In 1846, fifty years after the settlers from Santa Fe first arrived in San Miguel, the US military under General Stephen Kearny entered the area. The United States had declared war on Mexico, long desiring possession of its California ports, and Kearney led his men down the Santa Fe Trail to establish a US provisional government in New Mexico. In Tecolote, San Miguel, and San Jose, Kearny climbed on the roofs of buildings, gave a stern warning to the people that they must swear loyalty to the United States or face death. Kearny promised that the US would protect their life, property, and religion. In San Miguel, the priest and the mayor objected, saying that they would not commit the sin of renouncing loyalty to their nation, Mexico. When the United States won the US-Mexico War and signed the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the San Miguel del Vado grant became part of the US. Kearny's promises of protection would not hold. As Malcolm Ebright writes, "The story of the settlement of the communities within the San Miguel del Bado grant contains the seeds of a tragic loss, the loss of all the common lands." Over the course of three decades, the American government was able to reduce the size of the San Miguel del Bado Land Grand from 315,300 to 5,000 acres. A US Supreme Court ruling in the United States v Sandoval (1897) ruled that the communal lands passed from the Spanish government to the Mexican to the US governments. This ruling was in opposition to Spanish and Mexican law that said communal lands were owned by the community and not the government. When a special commissioner was appointed by the federal government to assess the boundaries of the San Miguel grant, he found 5,000 residents living there on a little more than 3,500 acres divided into ten tracts. In the 1960s, the Trustees of the San Miguel del Bado land grant transferred land to create the Villanueva State Park. Following the Sandoval case, no communal land grant was ever confirmed again, leading to the loss of perhaps millions of acres of land belonging to Spanish Mexican families in the Southwest. For a great article by Malcolm Ebright, see "San Miguel del Bado Grant" at http://newmexicohistory.org/places/san-miguel-del-bado-grant. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022