|

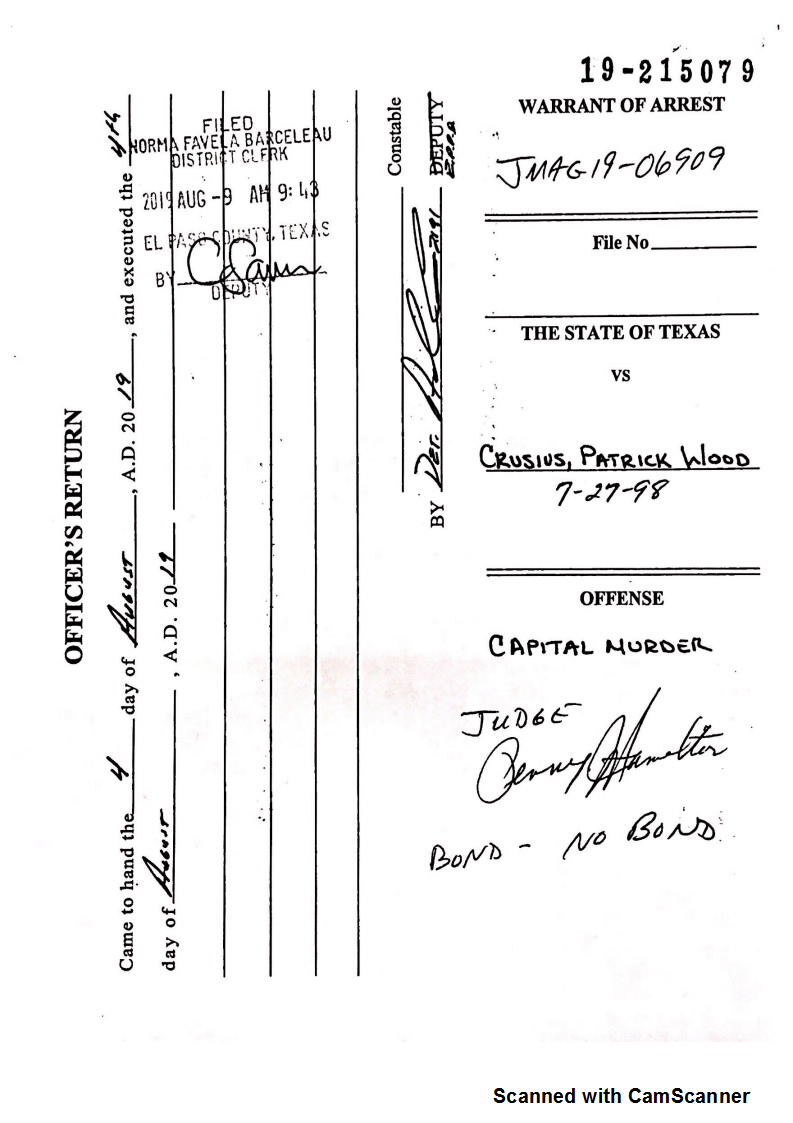

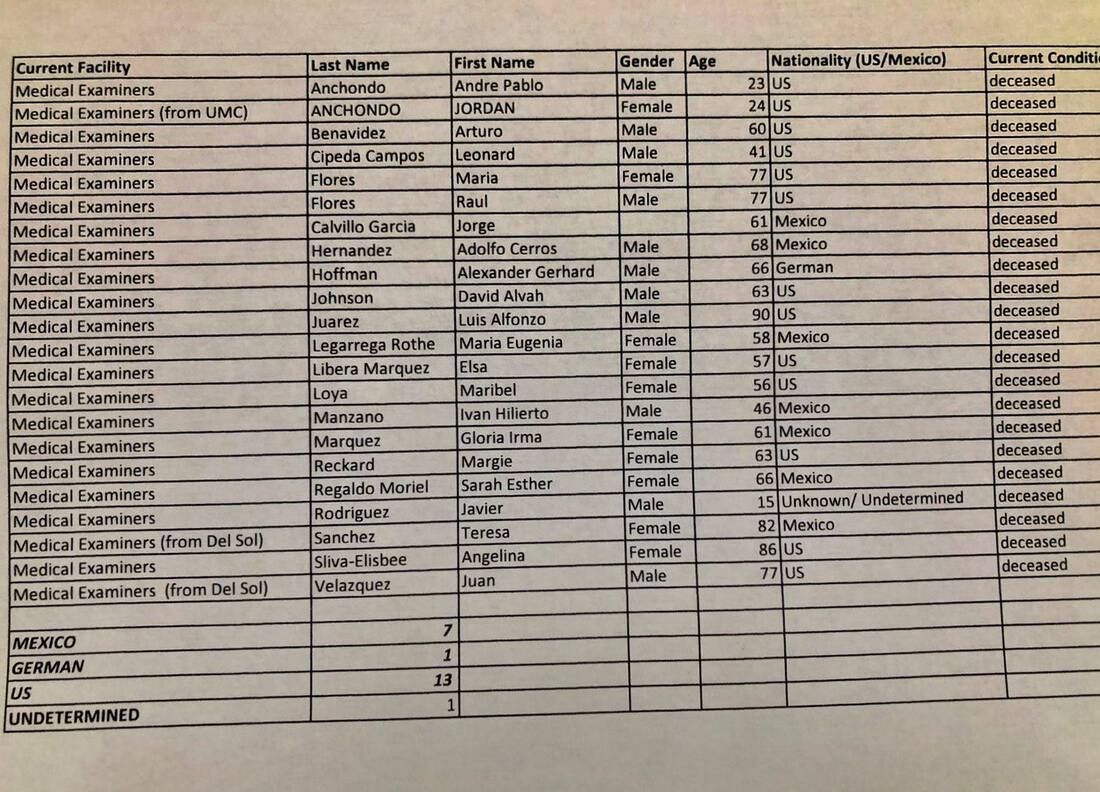

The Saturday before last, my grandson and I sat in my car preparing to go to a movie to celebrate his 14th birthday. He is a compassionate, creative, funny boy who notices the way that the sun makes the trees sparkle at my work. He writes poetry every day. He works hard to do the best he can while living with autism. I had just heard the news. “Mijo, there’s a live shooter at the Walmart at Cielo Vista.” His immediate response was, “Abuelita, they want to kill Mexicans.” I was shocked at his statement. “Did you hear that on the news? Are they saying that?” “No, I just think that. I know that.” The police report proved him right. "The defendant stated his target were 'Mexicans.'" Meanwhile, early reports were blaming it on gang violence, something that most of the people I have spoken to immediately dismissed. On August 2, a young white supremacist drove close to 650 miles to my hometown to carry out a massacre. He killed 22 people and injured over two dozen more. The murdered ranged in age from 15 to 90. Police attribute a racist, rambling essay to him that was published on 8chan shortly before the killing. In that document he talked about responding to the “Hispanic invasion” of Texas, an ahistorical statement that I addressed here. El Paso is not a small town but we function as one. I know people who were in the Walmart when in happened. The mother of one of my closest friends tells her story here. I know people who lost family members to the white supremacist. I know many people who wake up each day frightened now. Students are reaching out to me to talk about their futures. I am scared. Many of us are retraumatized by the massacre. My friend Teresa talked about this in a public meeting the other day where we discussed what actions to take now. On the border, we are constantly traumatized and retraumatized. For almost three years, I have worked with the people of Barrio Duranguito, the first platted neighborhood in our city and an area that the mayor and City Council have pledged to demolish for a sports arena. The neighborhood is low-income with an average annual income of $9,000. It is majority women over 65 and it is almost completely a barrio of renters who are vulnerable to negligent landlords. When residents began to organize against their displacement and the destruction of their historic neighborhood in 2016, the City and the landlords responded violently. The property owners hired a manager who harassed the residents day and night, calling them endlessly, knocking on their windows at night, threatening to have their utilities cut. While the City had to offer financial assistance to the residents by federal law, it was the constant threats and the effects on their health that pushed many out. Last November, the City shut off access to the street by installing a fence. It has isolated the remaining residents on that street. They wake up each morning to an ugly, green fence. The mayor has a thing about fences, we know. I think back over just the past year and reflect on the trauma and suffering we have witnessed on the border. The constantly changing federal policies imposed by Trump that keep us in a continual state of imbalance. My partner and grandson were preparing meals for asylum seekers at shelters through the refugee meal program at the Borderland Rainbow Center. They never knew how many people ICE would release that day—would it be 50? Would it be 200? For community organizations and volunteers, it was a matter of never knowing how to prepare to assist the refugees, day by day. We saw hundreds of asylum seekers penned in under the international bridge, like animals, sleeping on the gravel. The bridge is just six miles from my home. It was heartbreaking. Once, I gave a ride to a young mother and her toddler. Her daughter had a terrible cough and when I asked why she was sick, her mother told me they had spent five days under the bridge, suffering the night time cold weather, eating frozen burritos given them by ICE, and sleeping on the ground. Recently, I interviewed another mother whose 5-year-old became so sick during their time jailed under the bridge, that she became unresponsive. When the mother begged for medical care for her daughter, the officer told her, “Don’t worry. She’s not dead yet.” After they were released to a detention facility, the little girl would not eat. She could not talk for days. The inhumane treatment of asylum seekers gained wide media coverage such as this article in TIME. Last Wednesday, a white supremacist from Houston came to our city where he harassed mourners at the memorial created for those killed in the Walmart massacre. Later that day, he went to Casa Carmelita, a shelter for migrants, with a loaded gun and a knife. The El Paso Police Department detained him but later released him, telling the organizers at Casa Carmelita that “he had rights.” Casa Carmelita is not the first place he has threatened. There is a stock photo of him in from of the library that was hosting an LGBTQ event in Leander, Texas.  Screenshot of a stock photo site featuring the white supremacist who came to El Paso following the Walmart massacre. Screenshot of a stock photo site featuring the white supremacist who came to El Paso following the Walmart massacre. Last Friday, I visited Respettrans, the LGBTQ migrant shelter in Ciudad Juárez. It is a welcoming place. It is more than a shelter, it is a home for the transwomen, gay men, and lesbians who are seeking refuge. When I arrived, the founder of the home, Grecia Hernández, had just returned from the morgue. Each time a transwoman is killed in Juárez, the authorities call her to see if she can identify her. She didn’t know her, but the details of the murder were not unusual. “Another woman beheaded,” she told me. Violence, individual and structural, against the poor, against migrants, against women, against queer people, against Brown people, against the most vulnerable among us is everywhere in my city. It is also true that my binational community is filled with caring people who will and have come together to help others. There are people here who have very little yet will give what they have if someone is hungry. We have always been that kind of place. We are both: a place of violence and a place of love. My family, my friends, my students ask where do we go from here? What do we do now? Organizations in the city are providing counseling, as is my university and our school districts. This is an important first step to deal with the shock we are experiencing. I’m grappling with what to do next. I’m talking with folks about what specific actions to take next, both individually and as a community. I’m looking to history to see how our ancestors fought white supremacy and what worked and what didn’t work. I’m writing, finally, after a year because it is therapeutic. And I’m turning to my spiritual practices to ground me. It is a time for us to come together to talk in a real way about the hatred and white supremacy in our city, in our state, and in our nation. It is not new and the fight against it is not new either. Join me.

2 Comments

|

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022