Today I share a piece I wrote in 2008. It is still true. I believe it with all my heart. How do family traumas keep us trapped and ill? Let me know your experiences. Growing up I became the somewhat reluctant carrier of women’s stories—mothers, aunts, grandmothers, sisters. They were mostly stories of pain, abuse, and poverty. The kind of stories that generations of women have kept secret or shared in whispers with other women, sometimes in shame, sometimes in desperation. The kinds of stories that speak of the weariness of the soul, yolmiquiliztli our ancestors called it. The young mother, tormented by her father’s incest, whose tortured mind wouldn’t allow her to keep her children, wandering self-destructively through life wondering if they knew that she loved them. The grandmother who died at forty, disillusioned at her impoverished life in the new country, always remembering the life she had left behind in Chihuahua before la Revolución took everything away. The tía abuela who gave birth to a baby boy, alone in a small dirty tenement bathroom in el Segundo Barrio, immediately handing him over to a stranger to raise. The tiny baby girl who spent the last days of her life with her stomach cramping, the burning pain of an intestinal disease filling every inch of her fragile body, who found it easier to let go of the spark of life than to fight the pain of the extreme in the sandy desert outside of Cd. Juárez where half a century ago clean water was and continues to be a luxury. There were also stories of fighting back, of strength, and of humor. The young wife who hit the border patrol agent with her purse for disrespecting her dark skinned husband, in his army uniform, as they crossed the border. The sister who pushed her wife-beating brother-in-law out a two-story window in defense of her older hermana. The young girl who went each evening, her heart sparkling, to find a secret love letter from the young man who courted her, hidden between adobe bricks, away from disapproving parental eyes. Hesitantly, I listened to the stories over and over as a girl. Having heard them repeated over and over, I memorized them unwillingly. Over the decades, these stories made a home in my body where they settled, often uncomfortably, in my most vulnerable women’s places—my uterus and my heart. From adolescence on, I bled uncontrollably each month, cramping so violently that sometimes I fainted. By my thirties, tumors had begun to grow in my uterus, increasing the monthly pain. Doctors urged me to have a hysterectomy.[1] Hysterectomies, a decade ago as now, were the frequent answer to such conditions. My heart, no yollotl,—the place that our ancestors saw as the residence of vitality, knowledge, will, and affection—suffered as well. For years, I experienced yolmiquiliztli, the weariness of the heart, literally the “death of the heart.” I believe it was passed on from generations of women before me, some of whose stories I knew and others that I did not. I carried their pain in my cells as if it were my own, and it was mine although I had not directly experienced their suffering. [2] I tried to awaken my heart and deaden the pain through external means, self-medicating in all the ways that modern society offers us. However, it only served to separate me more from my corazón and from myself. The more I tried to forget the pain, to distance myself from the stories, the more I forgot my true self, my human self. Our ancestors had a word- yollopoliuhqui, which meant “lost from the heart” or forgotten. It also meant “strayed from the heart.” or careless. I was both. Like so many, I took risky chances. I didn’t listen to my instincts. And I often lived in fear. One day, in my mid-thirties, returning from an appointment with a persistent doctor who insisted that removing my uterus was the only way to stop the pain, I had an idea. What if the tumors represented the women’s stories that had nestled in the tissue of my uterus, and what if writing them down allowed my body to release the painful, hard tumors? I began slowly, hesitantly writing them. It was difficult. I had carried them for so many years, keeping them secret as I was taught. I felt fear and guilt for putting the stories down on the paper, but I continued over several weeks. When I returned to the gynecologist’s office a couple of months later, she was surprised that some of the tumors had disappeared and that others had shrunk. I was elated, but stopped writing the stories. I don’t know if it was the shame and secrecy that the stories embodied or whether, after so many years separated from my heart, I didn’t have the discipline or the self-love to continue. A decade later, the tumors were back and, again, doctors began to urge me to have a hysterectomy. At age 44, I finally agreed and my uterus was removed. I was traumatized and saddened following the operation. Physically, it took years for me to feel “normal” again. But the shock of having lost my uterus pushed me into action and I returned to writing the stories. Out they came, mostly as poems, and I began to read them out loud in public and to publish them. Suddenly I could hear the generations of women before me who began to call on me to tell their stories in ways that were truthful and respectful. My heart began to open again. Yolmiquiliztli, the weariness of heart, the death of the soul, has another aspect. The great maestro of our culture, Arturo Meza Gutiérrez, writes of the concept of miquiztli, death, as inevitable. Yet he also calls it “el sueño reparador que genera ideas positivas.” My death of heart had transformed into a period of rest just prior to the emergence of a new life. Like madre tierra, who appears dead and lifeless during winter, only to reemerge green and filled with life in the spring, telling the stories had brought me back to life, back to my humanity, and back to myself. My heart knew that healing was possible; I felt it and I worked towards it. Acknowledging the stories, writing them, and telling them had initiated the process of healing. Not just for me, but also for those women whose stories I had carried for so many decades, painfully in my body. The trauma of our stories, as individuals, as families, communities, peoples, nations, as humanity, cannot be ignored. It cannot be self-medicated into oblivion. I learned that to remember, in a conscious way, was part of the healing. I learned that to tell the stories in ways that honored that generations that came before us was to heal. I learned that my heart/our heart could awaken again. [1] Today, approximately 600,000 women in the United States endure hysterectomies each year. Women’s health advocates argue that up to 75% of these life-changing surgeries are unnecessary. They are among the most common surgeries for women. [2] Today social workers, psychologists, and other scholars write about historical trauma. The suffering of our ancestors and our peoples whose effects continue to be felt for generations, even if the precise details have been lost or sometimes purposefully forgotten.

0 Comments

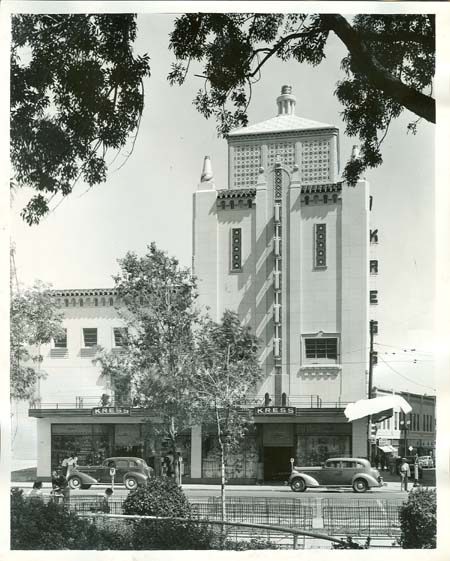

Today, the Kress building downtown is empty, lifeless, dark. But once, it was full of life. Growing up in the late 50s and early 60s, my mama and I frequented el centro para pagar los biles. Back in those days, we took the bus downtown, walked to the electric company and the water company and La Popular, the city's most historic and popular department store. Although the trip was always tiring, I knew at the end of our visit, we would go to el Kress and sit at the diner and eat burritos. They were the best burritos I ever had. After our burritos, we'd wait at the Plaza de los Lagartos, catch our bus and head home. It was a monthly treat I enjoyed until I entered first grade. In the 1980s, I'd relive those times, going with my partner Frances and our son to el Kress, walking through the aisles and aisles of chincho and having a great time. Eating burritos. The last time we were there was during the Christmas season in 1990. I remember it clearly because a month later, she committed suicide. The following year, el Kress closed.  I've loved el Kress my whole life. Many people feel the same. It was such a profitable store that it was part of the reason the Kress Foundation donated 58 pieces of art to the El Paso Museum of Art. It is a story that probably few people know. The thousands of Mexican shoppers who visited el Kress helped the museum acquire a beautiful collection of Renaissance and Baroque art. It's part of the invisible history of how Mexicans built this city.   After the store closed, small businesses opened, serving the countless people who waited for buses at la Plaza de los Lagartos. The little stores seemed to be overflowing from the doors of el Kress. When the City moved the bus terminal south, the small businesses around la Plaza closed.The chair and lock announce no more small businesses catering to Mexican shoppers. The City's plan is to de-Mexicanize our downtown and turn it into a place of expensive small restaurants and trendy bars owned by El Paso's elite. I wonder if we'll end up with a beautiful and expensive donation of art based on the number of margaritas they drink or fancy appetizers they eat. In 2009, while visiting my compadre at his apartment on San Antonio Street, I realized that I was standing in front of the first location of the first gay bar I ever went to-- the Pet Shop. I first went to the Pet Shop in 1974 and I will always remember walking down the dark flight of stairs and entering the crowded bar filled with disco music. The first time was magical. I was beginning to recognize I was a lesbian, not quite sure what that would mean in my life, and I only knew a handful of gay men and no lesbians. Then that Friday night, I opened the heavy door and began walking tentatively down the dark staircase into the unknown. Multi-colored lights flashed from under the dance floor, couples danced, and the music blared. How I loved disco music. Earth, Wind, and Fire. Donna Summer. Sister Sledge. Dancing the Hustle. Listening to Boogie Wonderland. Ah, the memories of dancing for hours on the brightly lit dance floor. When I entered the now dusty, forgotten space 35 years later, I got up on the dance floor and danced. When the Pet Shop moved down the street to another location on Ochoa Street, I remained a loyal Friday and Saturday night customer. It was there that I met Lee and her wife. They became my lesbian mentors, taking me under their wing. I thought of them yesterday as I drove through Orogrande, New Mexico. I always remember them when I drive through the almost de-populated town that once boasted a population of 2000, drawn by the discovery of gold at the turn of the twentieth-century. The 2010 census says it has about 50 people now. Many of the buildings in Orogrande are abandoned now but I still remember Lee when I drive down US 54 accompanied by 16 wheelers and the occasional car. Lee was a butch truck driver who often made the lonely drive down 54. One day she stopped at a tavern to have a drink and met the woman she would fall in love with. For some reason I can only remember Lee's name. The woman who served her that day had beautiful golden hair that she wore in a big hairdo like Tammy Wynette. She was friendly and called Lee "honey." They fell in love and soon Lee and the beautiful blonde and her five children were a family living in Orogrande. Lee kept driving trucks and her wife became the postmistress of the town. Every weekend they would drive the fifty miles to El Paso and go to the Petshop. One night the beautiful blonde told me, "I didn't know Lee was a woman until the first time we made love." That's how butch Lee was. In a bar full of Mexicans, a rural white couple became my lesbian mothers. (I had a Mexicana lesbian mom, too-- La Gloria. But that's a different story.)

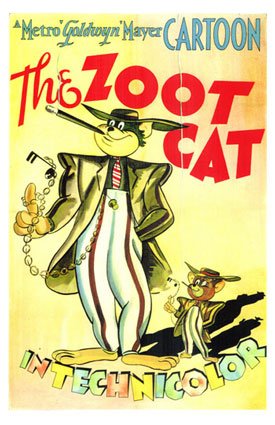

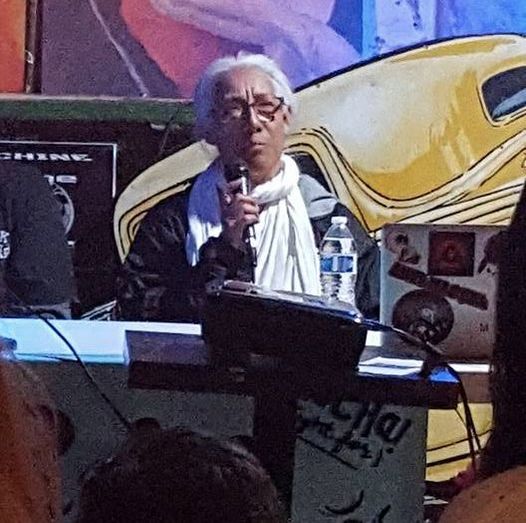

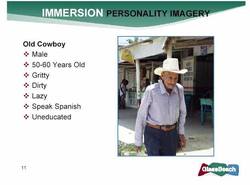

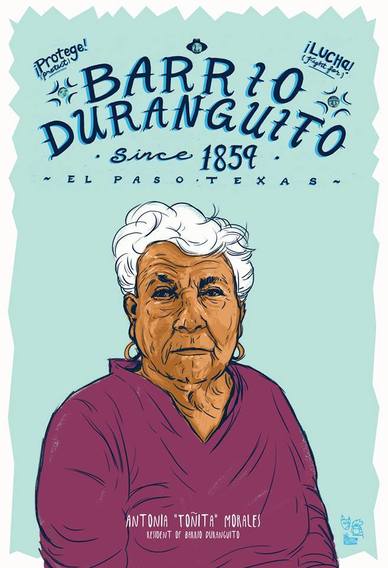

I was a shy baby dyke back then so they let me sit with them, sipping beers. One night they met a young white butch and brought her over to meet me. She was equally shy. They tried to encourage us to talk to each other, but mostly we just sat there and nervously looked at our beers. One of the last memories I have of them in 1975 before I left El Paso for Austin (and learned how to be a politicized lesbian) still haunts me. Lee had gone off to the restroom and returned flustered, red-faced, crying. "They kicked me out of the ladies room. They didn't believe I was a woman!" she told us. I had never seen her like that before. "I am a woman," she cried. Out of the many memories-- the police coming in and making everyone go outside so they could check our ID cards, the gangs of young boys that hung out outside waiting to harass us, their failed attempts to get me a girlfriend, this is the one that stays with me most. Lee and her wife inspired me. They showed me that love and family between women was possible. In a time when bars were our only place to form community, where often our interactions were fueled by alcohol, where we sat in dark and smokey rooms, they showed me the possibility of queer life outside this setting. Not that I didn't love the bars-- not just the Pet Shop, but later the OP, and in Austin, the Hollywood-- but I needed more hope, more possibilities. Each generation of queer people helps teach the younger generation about our culture, our relationships, how to be. I am grateful for Lee and her beautiful wife and all they taught me.  During World War II, my mama prayed... a lot. Day and night she prayed for her baby brother and nephews and for her husband to return from war. In between praying, she cried. She often felt hopeless. One day she went to el centro, downtown El Paso, to try to get her mind off of her worries. On her way home, she looked up at the sky. In El Paso, the sky is broad and the clouds are magical. She was wondering how her brother was-- he was so young. Walking through the unpaved road towards her mother-in-law's house where she had lived with her husband for many years, she glanced up. She couldn't believe it. In the clouds, in an opening, she saw Jesus. He was looking down on her with those compassionate eyes that you see on Catholic prayer cards. Looking down on her and giving her hope with those beautiful, compassionate eyes. That day she knew they would all come home safely. And they did. One by one, her husband, and her baby brother, and her nephews returned from the Pacific and Europe. While her husband came home wounded and spent a year in a body cast, he had come home. She told me this story all my life. My mama was a hard woman, bitter and distrusting after a lifetime of suffering. But when she told that story, she softened. It was a miracle that Jesus had shown Himself to her that day, walking on Pera Street through the dusty streets, past adobe buildings and corner grocery stores. It was the miracle of her life. I've been remembering that story recently in these times when it is so easy to feel hopeless. And I wonder what miracle will manifest itself in our lives, in our nation, in our world? How will we connect to the vastness of the sky, of the heavens, and gain the strength to live with hope? Thank you to Joaquin Leyva for permission to use the photo of the double rainbow.  Today I found an ancient, primitive website from when I moved back to la frontera more than a decade and a half ago. I wrote about aguacates and the Plaza de los Lagartos. About how much I loved being home again, after several years teaching in another city. Some of it has remained the same. And much has changed. Aguacates are readily available now in supermarkets. The 1990s Operation Hold the Line had limited the supply of aguacates sold door to door by women crossing the border with baskets of the delicious fruit. The Plaza de los Lagartos (San Jacinto Plaza) has been effectively de-Mexicanized by a partnership between the City of El Paso and a local billionaire. A few years ago the City of El Paso moved the buses south of Paisano. Now the people no longer come to the plaza and the small businesses are gone. The once vibrant plaza, filled with elders and young people hanging out, sitting on the benches and visiting, surrounded by small businesses selling food and drink, has just a few people. Now, it is surrounded by high end restaurants and bars, some owned by the billionaires. There is a "cafe" at the plaza now with small tables. A bottle of water and a cup of corn cost me $6 last Sunday. Now it is perhaps "prettier" but it is no longer the heart of downtown. The City continues its efforts to de-Mexicanize our city. A decade ago, the City of El Paso paid a branding firm, Glass Beach, $100,000 to produce a study of El Paso. The firm was affiliated with the Paso del Norte Group, a secretive group of El Paso's elites and their friends on the City Council. They had already introduced the downtown "revitalization" plan that included the demolition of a huge section of El Segundo Barrio, one of the most historic and vibrant Mexican American neighborhoods in the city and, indeed, in the country. We knew that the City wanted to rid our town of poor Mexicanos but this study made it clear. The slide below, from the study that was approved unanimously by our City Council uses words that have been used against us for almost two centuries, particularly "dirty" and "lazy." Not one of the City Council stood up for our people or culture. One was the son-in-law of the founder of the Paso del Norte Group, Roberto O'Rourke. (He goes by Beto but I won't call him that... it allows some people to consider him "Mexican" and he is not.) He is now a US Representative who is running for the US Senate. People talk about how he "loves Mexicans." Another supporter of these studies, Susie Byrd is on the School Board. The then Mayor, John Cook, now works as a lobbyist for the wealthy elites he catered to as an elected official. Recently, Cook has been lobbying for the demolition of another historic Mexican American neighborhood and the displacement of a community of mostly older women. Somehow they have been able to maintain their reputation as progressives. Still, I love la frontera. It is a place I can never imagine leaving. Below, I share below what I wrote when I first returned sixteen years ago. ********************** I was born and raised on the Texas-Chihuahua border, a place that is both beautiful and sad. I loved growing up here. La frontera is a place where people eat turkey mole on Thanksgiving, where mueblerías, furniture stores, illustrate their annual sales with images of soldaderas, where every morning people cross the river with tortillas and aguacates to sell in middle-class neighbors on the U.S. side. La frontera is a place where my elementary school mandated compulsory Spanish lessons beginning in first grade while my primos on the southside were spanked for speaking in that very language on their school grounds. La frontera is a place where several years ago I was detained by Customs for trying to smuggle a mango, a reddish-golden, sweet-smelling mango, across the border in my purse. I wanted to bring it home with me to remind me of México, that long-lost sweet homeland of my immigrant parents and grandparents. La frontera is where my identical twin sister, Elisa, and I were born in the mid-fifties in a small medical clinic near downtown Juárez. She stayed with our mother in Juárez and died of an intestinal virus, still the biggest killer of Mexican children on the border. I was taken to the U.S. side where I grew up. Elisa is buried in an unmarked grave in the municipal cemetery in Juárez. Because of her, I know a part of me will always be on the other side, el otro lado. In downtown El Paso there is a plaza. Poor children from Juárez cross each day and hide in the underground bathrooms there, selling sex for survival. No one sees them unless they know to look. They are invisible, like so much of what happens in the place where two nations and many different groups of people meet. We have to look below the surface to see what is really happening. The border is a beautiful and sad place. Because of this, I have spent a decade studying it and a lifetime learning the stories of its people. I didn't mean to stare at him, but I did, drawn in by the deep rich purple of his zoot suit and his calcos, and his black tanda with a feather. I stood behind him in line at the cafe at Sagrado Corazon Catholic Church. I never saw his face but I liked that. He represented more than just a man dressed in a beautiful zoot suit. He represented communal memory and history to me. I don't know when I first knew about the zoot suit, but I grew up hearing Caló, that beautiful mixture of Nahuatl, Romani, and archaic Spanish. And I grew up hearing about the pachucos who first started in El Paso. In a 1978 oral history with Geronimo Leyva, born in 1910 and raised in El Paso from the age of 4, he talked about the migration of young men from El Paso to Los Angeles in the late 1920s and early 1930s. "Entonces oía decir yo mucho de los chamacos, los chavalos, teenagers. Decian 'Pa' dónde vas? "Pa' Los’ y ‘Pa' Los’ y ‘Pa dónde vas?’ y ‘Pa' Los.' Puro "Los." Ninguno decía que para Chicago o otra parte. Pur ‘Los’ y que ‘Los Angeles’… You know what? Ir a sufrir los pobres porque no se ponían a trabajar. Del modo que Vivian los pobresitos no más se iban a la city market a buscar bananas, old bananas, old rotten apples y todo para vivir. Para estar comiendo durante los días. Yo los llegué a verlos, los pobres." My father would tell me the stories of how these young men who had gone to "Los" and suffered would say return to El Paso during the Great Depression, riding the boxcars and saying, "Vamos pa' Chuco." While many people think El Paso's nickname, El Chuco came from pachuco, it is reversed. Returning home, they became los "vamos pa'Chucho." My childhood cartoons even featured the zoot suit. Although some had been made a decade before I was born, they still lived on our black and white television set. This is a poster for 1944 The Zoot Cat. The poster art copyright is believed to belong to the distributor of the film, the publisher of the film or the graphic artist. From Wikipedia. Of course, growing up I heard about German Valdes, "Tin Tan," perhaps the most famous pachuco of his time. When Dr. David Dorado Romo and I founded and directed Museo Urbano in El Segundo Barrio, many of the older women told me that they had been his girlfriend. My own mama, in fact, talked about going to Juarez to see him perform and his asking her on a date. Of course, she was already married to my father so nothing happened. Once, walking in downtown Mexico City, a man selling photos of revolutionaries and movie stars handed me a photo of German Valdes in a zoot suit."Ud. sabe quien es?" "Pues, es Tin Tan," I answered. "Como sabe eso?" "Soy del Chuco," I told him and we both laughed. Tin Tan and his friend, Marcelo.  David Flores of Colectivo Rezizte (left), Antonio Lopez (top right), Maru Lopez and Eddie Garcia (bottom right) paint "Pachucos Suaves" in El Segundo Barrio, 2011. In 2010, David Romo and I commissioned a mural for UTEP's Museo Urbano. Internationally-recognized muralist whose work was recently featured at the Smithsonian Cooper Hewitt Design Museum in NYC, David Flores designed and painted the mural. The mural, Pachucos Suaves," featured the archetypal pachuco seen above as well we Edmundo Tostado aka Don Tosti, the famous musician and composer who in the 1940s wrote "Pachucos Suaves," earning him the title of the first Latino to sell a million records.  Don Tosti as portrayed on the "Pachucos Suaves" mural. He was born and raised in El Segundo Barrio and, much like the "chavalos" from the oral history quoted above, moved to "Los" as a young man to make his way in the world. Unlike the teenagers who had to look for old fruit to eat, he became a very successful musician and composer.  The man in the purple zoot suit gave me much to remember and think about as he stood in line for menudo Sunday morning. What about the zoot suit still captures our imagination so many decades later? How is that history passed on from generation to generation? Why does this outfit resonate with so many so many decades later? I didn't mean to stare at him, but I did as he walked along the streets of El Segundo, the home of the pachuco. [Oral history excerpt taken from interview of Geronimo Leyva by Yolanda Leyva, May 1978, deposited at the Benson Latin American Library, the University of Texas at Austin.]. Yesterday, a group of us met with a local TV station to discuss their coverage of the demolition of a historic neighborhood in my city that would result in the displacement of a long-time and close-knit community, mostly elders. Three of us, community organizers and historians, accompanied four women from the barrio. They were from their fifties to their eighties. The women were eloquent, witty, and incredible fountains of knowledge about la frontera. Doña Carmen in front of the Civic Center protesting for the right to remain in her home, 2006. Señora Lupe at a meeting to defend El Segundo Barrio, 2006. Margarita speaking on behalf of her small business, 2006.As I enter my elderhood, these women are my guides, my heroes. They have raised generations of children. They have worked long hours inside and outside their homes. Their work has built this city. They have spoken in defense of their homes and their communities. I've seen them work an 8 hour day and then walk miles to their second job. I've seen them go house to house to talk to neighbors, organizing the neighborhood. I've listened to the stories of how they have spent years making their barrios safe and tranquil places to live. And they can still tell a joke and dance and laugh. They have hope and they take action. No, Mr. TV Station Man. We are not cute. We are fierce.  Doña Toñita, la abuela del barrio. Photographs courtesy of Lucia Martinez and Paso del Sur. Thanks to Zeke Peña and Los Dos for use of the Duranguito poster.

|

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022