What happens when a building loses the humanity that once inhabited it? When its history is hidden from people? In another post, I wrote about how buildings are killed, sometimes by neglect but also conscious attacks on the history. A few days ago, I walked in El Segundo Barrio where Dr. David Dorado Romo and I once directed a community museum on S. Oregon, Museo Urbano. In 2011, our landlord raised the rent in the belief that the on-going "revitalization" of downtown, just north of El Segundo would allow her to almost double the rent. We couldn't afford it. We were forced to move. The space remained empty for quite a long time and then at some point, a new owner took over. The building, which lies at the center of El Segundo's Mexican community to the south; the historic Chinese community to the north; and the history African American community to the east has a rich history reflecting the different cultures that once thrived there. When I saw the building, once alive with history and people, I stopped in my tracks, the memories of six years ago flooding back. On opening day of our Museo Urbano on S. Oregon in 2011, we had over 700 visitors. People of all ages came to enjoy the festivities and view the exhibits that graduate students, artists, and others had created. They came to share stories of growing up in El Segundo in the 50s, in the 20s, and more recently.

The building, once alive, is now dead. The murals have been painted over with beige paint. Ironically, the artwork by David Flores that once enlivened the building was featured in a museum exhibit at the Smithsonian Hewitt Cooper Deigns Museum recently. The courtyard where people danced and gathered to tell stories now has a "no trespassing sign."

0 Comments

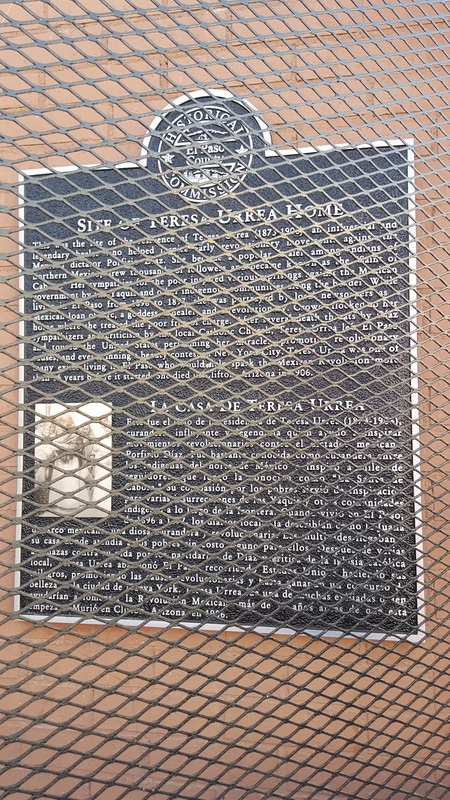

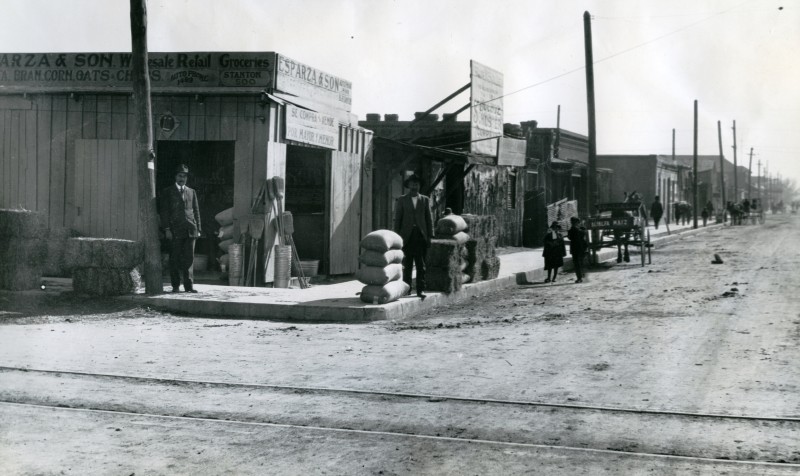

In 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression, hundreds of Mexican American women formed La Asociacion de Trabajadoras Domesticas/ The Domestic Workers Association. What can we learn from them? Listen to the podcast! Visit Fierce Fronteriza at SoundCloud, too! https://soundcloud.com/user-858745308 I love shopping in El Segundo Barrio. In the 1980s, I used to buy big bows for my hair. In the 1990s, I used to buy playeras, t-shirts, with Aztec figures on them. As I grow older, I no longer have the need for things. Now, just the experience of walking through the shops with their arcangels and booty mannequins. Looking at the colors and variety of cositas give me joy. Here are some photos from my recent visit to El Segundo. From its beginning, the barrio was filled with small businesses catering to the Mexican immigrant population. Today, many of the stores are owned by Korean business people who are trilingual. The majority of goods are made in China, including those that appear to be Mexican-- small bags with the image of Frida Kahlo or those made with fabric that mimics the traditional fabrics of Mexico. The relationship between Mexico and China is hundreds of years old, going back to the colonial period. The first shipload of Chinese goods arrived in Mexico only fifty years after the Spanish gained control of the New Spain. In recent years, Mexico has started to import the chile de arbol, once an important product of Mexico, from China. It was a bittersweet shopping trip, finding bargains while thinking of the workers who are paid so little that I could buy a wallet or a small purse for $1.  Above: Esparza Grocery store, turn of the 20th century, S. Stanton and Fifth Street. Courtesy of Digie, El Paso Museum of History.  Above: Mural of Father Harold Rahm, the "bicycle priest." He came to El Segundo in the 1950s and did much to divert the energy of gang youth in a positive direction. He was a Jesuit priest at El Sagrado Corazon, an ex-boxer who, the elders of the barrio have told me, would challenge young men to fight him. If he won, they would leave the gang. He always won. He is in his 90s and now working in Brazil.  El Segundo Barrio, El Paso's Second Ward, is one of the most important Mexican and Mexican American barrios in the United States. Thousands trace their family roots to this barrio because El Paso was the main port of entry for most of the twentieth century. My own family started its US history in El Segundo Barrio and the family stories live on of life there in the early twentieth century. This week, I spent a morning walking in El Segundo with my granddaughter and my partner, remembering my ancestors and their journey. Photo of my mother, Esther Chavez, in front of the presidio where she lived in El Segundo. It was here that her mother, Maria Lopez, died of pneumonia in 1927 and where her little brother Salvador, just a baby when his mother died, also passed away of a broken heart, missing his mama.  One of my favorite murals, Sister Cities by Los Dos. The sisters have their hair braided together. Like El Paso and Ciudad Juarez, the sisters are forever joined together. Despite the dividing line, the border fence (yes, we already have a border wall here), and the increasing fear of crossing, we are one community tied together by history, family and friends, culture, and economic interdependence.  Walking through El Paso I saw barbed wire and beauty, reflecting la frontera where I live. Even amidst the barbed fire, the fences, the presence of the Border Patrol, people create beauty everywhere. Entrance to an alley way. Last week, I saw this image on the Facebook page of Carlos E.C. Hagedorn. It immediately resonated with me as a fronteriza so I asked him permission to share it.

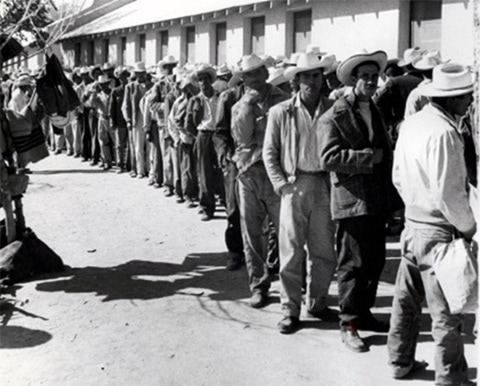

The caption for the photo says: Xicanx Studies curriculum: Maíz, Huitzilopochtli, Música, Abuelxs, Sin Fronteras. #ethnicstudies #nvesa The photo harkens back thousands of years to the beginning of our relationship with corn to our contemporary understanding of "sin fronteras," no borders, and to the abuelitxs' dreams for the future of our grandchildren. I'm wondering what five items I would use to create my own image. What would you use? Gracias, Carlos, for your vision!  On February 5, a commercial aired for 84 Lumber during the Super Bowl that has been alternately described as "pro-Trump" and "anti-Trump." On Super Bowl Sunday and in the following days, it elicited a lot of attention. While an edited, less controversial version made it on the Super Bowl, the longer version was easily available on You Tube. My liberal acquaintances are still talking about how it touched them. My immigrant friends feel that the ad manipulated people's emotions. The ad features a mother and a young girl walking through fields and desert scenes. The young girl picks up fragments of textiles along the way-- red, white, and blue fragments that she ultimately makes into a US flag by the time they reach the wall. When the mother and daughter reach the border, they encounter a giant wall, the kind that Trump wants to build. As they walk along the wall, they come to a door that opens for them. A beautiful ending. A touching ending. And one that is based on speeches by Trump during last year's campaign. In August, he promised to build "a big beautiful door," a promise he re-iterated in a November 2 speech in Pensacola, Florida. "We're going to have that big beautiful door in the wall but you know what? They are going to have to come in through a process. They have to come in legally." 84 Lumber's owner and CEO Maggie Hardy Magerko says she voted for Trump and the ad was about letting in legal immigrants. Perhaps the journey was not actually about walking across the desert at all. Perhaps it didn't purport to actually represent the true life experiences of thousands of migrants who risk their lives in order to survive. The journey is actually one of assimilation as the child picks up pieces of textile representing the US flag. It is not about compassion nor letting in a suffering mother and child. It is about packaging Trump's message of a wall and a "big beautiful door" in a way that is palatable and heart-warming. It makes us feel good at a time when Trump is considering separating mothers from their children at the border as a way to deter others from making the journey. Rio Vista Farm in Socorro, Texas may be the last standing Bracero processing center in the United States. During its time, thousands of men passed through these buildings on their way to work throughout the United States. In 2016, Rio Vista was named a National Treasure by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Contemporary photos by Yolanda Chavez Leyva. Historic photos courtesy of US Citizenship and Immigration Services.

|

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022