|

On this last day of the Gregorian year 2017, Fierce Fronteriza takes a look at the last century on the border. Please go to my Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/FierceFronteriza to check out the first Fierce Fronteriza newsletter! And to find out what this image is.... As we enter 2018, la lucha sigue!

0 Comments

Last week, I participated in a posada navideña, the re-enactment of Joseph and Mary seeking shelter before the birth of Jesus. The ceremony's history goes back at least 400 years in México and is celebrated in communities throughout Latinoamérica and the United States. It is a powerful recreation of a family seeking refuge. It is especially timely in these days of the global movement of refugees. I write this in the spirit of the Posada and inspired by Associate Pastor of Sacred Heart Catholic Church in El Paso, Fr. Rafael Garcia, SJ, who asked us last week to meditate on migrants seeking refuge as we walked through Barrio Duranguito. The United Nations reports that there are 28,300 people forcibly removed from their homes daily, representing 65.5 million globally. There are over 23 million refugees, half of them women and children. At a time when the numbers are growing globally, there is an increasingly hostile environment towards refugees and migrants. In the midst of this, Pope Francis has called on us to "share the journey." He asks us to see the people rather than just the numbers and to listen to the stories. A hundred years ago, as today, refugees cross our border seeking safety, seeking asylum. I invite you to read this story from 1919, written by reporter Harry Morgan who wrote for the El Paso Times about the refugees crossing the border during the Mexican Revolution and consider how much has changed and how much has, sadly, remained the same: Genuine pathos marked the flight of the Mexicans. Half clad women, their hair loose, fear written on their faces, ambled across the bridge, holding scantily dressed, and crying babies to their breasts. Shawls and blankets trailed in the dirt. To them the night of terror was just another page in Mexico's lengthy chronicle of revolution. To flee from their homes, leaving behind everything they possessed of worldly goods which, meager as it might be, was their all, was only a repetition of former experiences. To leave their humble homes in the wake of war and at the mercy of their fellow countrymen was not a novel thing, but its repetition made it no less terrible. Little children old enough to walk but incapable of understanding tagged along at their mothers' skirts, their eyes tearful, yet full of innocent wonderment. They had been born in the throes of revolution, and to them life had been little more than a recurring series of bloodshed. Mexican refugees crossing the border, 1914, Otis Aultman, courtesy of El Paso Public Library.

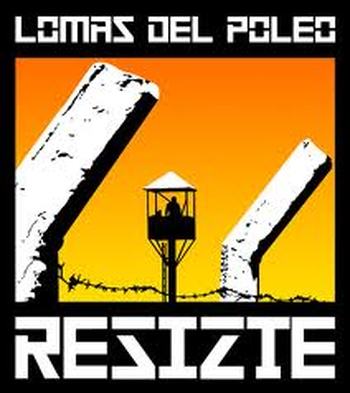

I live in the space between an ancient desert and the largest binational metroplex in North America. When I stand on my porch looking west, I can see the Franklin Mountains with their gobernadora, ocotillo, and nopal. The mountains pushed up sixty million years ago when tectonic forces off the west coast of North America caused the earth to crumple into glorious sierras. To the south lie the southern barrios of El Paso, and across the river, my birthplace, Ciudad Juárez. Once known as El Paso del Rio del Norte, Juárez had its beginnings in a colonial-era mission, la Misión de Guadalupe de Los Indios Mansos del Paso del Norte, dedicated on December 8, 1658. With humble beginnings in 17th colonization, in the 20th and 21st centuries, the city grew to be the largest in Chihuahua as internal migration brought thousands to the border, further stimulated by the development of the maquiladora industry beginning in the 1960s. Here on the border, I live my life in between the old and the modern, grounded between two histories. The Franklin Mountains, once known as la Sierra de los Mansos for the people who lived along the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo, has some of the oldest rocks in the state of Texas at over a billion years old. My home is constructed of rock quarried there. Tiny fossilized sea creatures, evidence of an ancient ocean that preceded the mountains, are embedded in the walls of my house. The mountains rise in the Chihuahuan Desert where my ancestors have lived for millenia and where each animal is a survivor and where each plant is medicine. Growing up in the 1960s, the creosote still grew on my street, harkening back to a time before houses were built when the land was still desert. When I moved back into my childhood home twenty years ago, I used to try to plant the wild desert plants in my yard but they never grew so I started to call out to the desert for her to send me the seeds. I prayed that they would take root in my yard. Slowly, they have been coming; the mesquite with its sharp thorns that has grown around my mailbox and a beautiful lluvia de oro that blooms in late summer by the front gate. The chiltepin with its tiny, hot chiles grows now. Years ago I visited Paquimé, Chihuahua, 200 miles southwest of El Paso, the middle place between MesoAmerica and the Pueblos in New Mexico. A thousand years ago the people built structures in the shape of butterflies and walls in the shape of snakes. When I looked at the mountains, I knew them: the way they turned purple as the sun moved across the sky, the way each hill curved around the other. I knew the sandy soil and the smell of the air. I was home in the desert that straddles both countries. Each morning I look west to the mountains and know that the history of the people who have walked this desert century after century is mine. To the south are the old barrios: El Segundo, Duranguito, and across the river, Bella Vista. These are the places that have welcomed thousands of migrants moving south to north in search of a better life for their families. It was in El Segundo where my mother, Esther Chávez , and her family began their lives in the United States in a tenement, long gone, on S. Stanton Street. Escaping the violence of the Mexican Revolution and leaving behind all they loved, she and her siblings learned English and went to Aoy and Bowie, the beloved and historic barrio schools once known as the "Mexican schools." Like generations of people living in diaspora, she remembered her birthplace, Ciudad Chihuahua, as a place where she was loved and safe. Here in the United States, she would say, everything changed. Less than a decade after moving here, her mother died at age 40 from pneumonia. Her father, grieving, distanced himself from his children and her older sister Mercedes became their mother-figure. When I walk the streets of El Segundo or Duranguito, I feel the histories in my bones. I hold them in my hands. I breathe them into my lungs. I know that a hundred years ago, my people crossed that river, walked that bridge into a new country, just as the people I see today. I remember the stories, the places, the feelings that have been handed down generation to generation among fronterizos. It is a gift to live here on the border between the ancient and the modern in the space between the desert and the city. I have a confession to make, one that is painful for me as a fronteriza. For ten years, I didn't go to Ciudad Juárez, my birth place, a city whose lights I admire every night, a place where my identical twin sister was buried 61 years ago in the panteon municipal, where I still have familia. I used to go regularly. Then the violence happened-- not just the drug-related violence that resulted in the deaths of thousands and brought Juárez the horrifying reputation of "murder capital of the world," but a violence that confronted me directly. It took me years to realize that I was traumatized. In 2007, Paso del Sur, a group I had helped found the previous year to fight displacement of poor communities in El Paso, began to work with organizers at Lomas del Poleo. The community built on a mesa, on the outskirts of Juárez, five miles from the international border, was a virtual concentration camp as Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Eileen Welsome reported here Dating back to at least 1970, the residents of Lomas built their homes of cinder block and wood pallets, raised chickens and goats, planted small fields and fruit trees, and left for work every morning. Then a group of wealthy developers decided that they would build a highway through Lomas, leading to a new maquiladora city San Jeronimo. Developers involved in this project overlapped with the same developers proposing the demolition of El Segundo Barrio in El Paso. It seemed logical to oppose their plans to demolish working class communities on both sides of the border. Beginning in 2003, the wealthy Zaragoza family of Juarez began attacking the peaceful community, claiming the land was theirs. By the time we became involved in 2007, the Zaragozas had build a barbed wire fence around the community and built guard towers. Homes were bulldozed while people went to work. Children died in a mysterious fire. An activist was killed. Eventually the community's lawyer would be assassinated on the way to court. The Catholic chapel was razed and Father Bill Morton, a American Columban father who had fought for the people, was expelled from Mexico. Eventually, the community's school was closed. Still, Mexican activists continued to fight for the rights of the people of Lomas del Poleo for years and the residents themselves resisted displacement. Lomas del Poleo protest, photo by Bruce Berman. Originally published http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2009/03/19/sociedad/048n1soc In 2007, residents and activists on both sides of the border came together to share stories and support each other. Under attack by overlapping groups of wealthy developers and confronted by a new focus on developing the border region as a place of global commerce, they had much in common. One action involved the people of Lomas del Poleo protesting in front of the American consulate in Juárez demanding justice for the people of El Segundo Barrio while the people of El Segundo Barrio protested in front of the Mexican consulate in El Paso demanding justice for Lomas del Poleo. You can view a video of this action here. Photos published by http://orpoin.blogspot.com/2007_12_01_archive.html In 2007, activists from Mexico and the United States came together for a forum at Lomas del Poleo. We were blockaded by young men with dogs, chains, and bats. Behind them stood a group of women taunting us. A man on horseback surveilled us, carrying a rifle. We called the police who said they could do nothing. We continued the forum, there outside the barbed wire fence. Poets like Dr. Selfa Chew read poetry to the pandilleros who were threatening us. Eventually we moved to the bottom of the mesa and continued the cultural activities and at the end of the day, took the bus back to our homes. I remember feeling outside of my body, watching the young men glare at us, threatening us with their weapons. The following month, I returned to Juárez for one of my regular visits, thinking I was fine. My visit coincided with the arrival of federal troops to the border city as part of what was then known as Joint Operation Chihuahua. Over the course of the next few years, President Felipe Calderon would deploy thousands of federal troops to Juárez to fight drug cartels. Walking down Avenida 16 de Septiembre that day in early 2008, a military truck drove by with a soldier pointing a machine gun at pedestrians. I remember laughing with my friend Lucia, but inside I was terrified. It was a month short of a decade before I would return to the place of my birth. In the months and years following our encounter with the pandilleros, Lomas del Poleo garnered international attention from organizations such as Amnesty International and the International Civil Commission for the Observation of Human Rights. Most of the people would leave although the remaining residents would continue to protest, including a four month protest in front of the offices of the subsecretary of state public education in Ciudad Chihuahua in 2011-2012. In 2013, the state governments of Chihuahua and New Mexico approved the new binational plan that would connect Santa Teresa, New Mexico and San Jeronimo, Chihuahua. The TECMA website touted the development this way: "What has been a rough, sandy plot dotted with little more than mesquite trees and scrub brush is steadily morphing into a US $412 million, state-of-the-art facility capable of facilitating the transit of billions of dollars in global commerce." You can read the article here. Like so many upsurpers in history, such a description makes the people of Lomas del Poleo invisible. There are a few families left but "development" is occurring in the once peaceful place where families built their homes and raised their familias. In this 2011 oral history-based documentary, "Colonia Perdida," you can hear the memories of people of what life was like before the violence: "Colonia Perdida." Doña Luci, resident of Lomas del Poleo, scene from "Colonia Perdida." When I finally returned to Juárez this week, confronting my trauma and fear, I remembered the people of Lomas del Poleo who suffered day after day, week after week, year after year in the face of threats, violence, and intimidation because developers wanted their land. Over the years, I've felt guilt that I stayed away so long because of that day in Lomas del Poleo. I wondered if I was just an overly sensitive estadounidense. But I know that day tapped into a deep trauma for me, perhaps carried over from the generations of my family who lived through violence. I also know that returning to the place of my birth, finally after all this years, allowed me to breathe again.

I remember Lomas del Poleo now not with fear and trauma but with respect and admiration for the people who fought and continue to fight for their homes in the face of overwhelming odds. Statue of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Barrio Duranguito, December 2017 Today, December 12, 2017 marks 486 years since Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe appeared to Juan Diego, a Nahuatl-speaking man in his late 50s. I have loved la Guadalupana my entire life. She has comforted me. Given me peace. Reassured me. She has healed me from my most profound wound. She has been my spiritual mother. As a child my father put me to bed telling me about the miraculous apparitions she made to Juan Diego and the incredulity of Bishop Juan de Zumárraga. I went to sleep dreaming of the rocky hill where she appeared, Tepeyac, visualizing it as the mountains up the street from where I grew up. When I looked at the stars as I stood in the backyard under the mulberry tree, I saw the stars on her cloak. When my mama and daddy and I went to mass on her special day, December 12, we watched the matachines dance to the boom, boom, boom of the drum. "Mija, yo era matachin cuando era chavalito. Bailaba descalso," he would tell me with a laugh. As the matachines shook their rattles to the rhythm of the drum, I imagined him barefoot, with black hair and brown skin, his skinny body dancing for la Virgen. For years, I took my students to the Basilica at Tepeyac where we stood on the modern moving walkway staring up at the ancient tilma with the image of the Virgen that had survived centuries and even a bombing attempt. On the grounds of the basilica, we sat on benches among the beautiful vegetation and walked up to the old chapel at the top of the hill. Each time I visited, it was magical. Each time I stood gazing on her image that was imprinted on Juan Diego's cape, I cried, standing there among the many who had come to honor her. It was there at Tepeyac that she appeared, as described in the Nican Mopohua, written by Nahua scholar Antonio Valeriano (1521-1605), who was a contemporary of Juan Diego. Valeriano described Guadalupe: "su vestidura era radiante como el sol; el risco en que se posaba su planta flechado por los resplandores, semejaba una ajorca de piedras preciosas, y relumbraba la tierra como el arco iris. Los mezquites, nopales y otras diferentes hierbecillas que allí se suelen dar, parecían de esmeralda; su follaje, finas turquesas; y sus ramas y espinas brillaban como el oro." When I first read this as a 20 year old student at UT Austin, sitting in the quietness of the Benson Latin American Collection, I was stunned that, like my own Chihuahuan Desert mountains, Tepeyac was adorned with the beautiful mesquites and nopales. One year on a trip with my students, suffering from pneumonia and a fever, I sat at Tepeyac wondering why she was so profoundly a part of lo mexicano. It came to me: together Guadalupe and Juan Diego symbolized the divine and the earthly in communion and with the most ancient symbols. Together they were the plumed serpent Quetzalcoatl, a concept we can trace back in Mexico for over 2,000 years. For hundreds of years, scholars have argued that she could not have said "Guadalupe," the name of an beloved Virgen in the medieval kingdom of Castilla, because she spoke to Juan Diego in his language, Nahuatl, that does not contain the letters "g" or "d." While numerous Nahuatl names have been proposed for what she actually called herself, the majority include the word "coatl," snake. My maestras and maestros have taught me that the snake represents the Earth because the snake crawls on its belly along the surface of the Earth. Juan Diego's Nahuatl name was Cuauhtlatoatzin, the eagle who speaks. The eagle, flying high in the heavens, represents the divine, that which is not earthly. Together, the snake and eagle, signify the earthly and the divine coming together. And the duality was even more significant to me because the Juan Diego, the mortal man, was the divine while Guadalupe, our divine Mother, was the earth. At the Basilica 2006 Because of my deep love for Guadalupe, I always wondered why my birth mother was also Guadalupe. I didn't wonder in everyday terms why she had that name= she was born on December 11 and I know countless Mexican baby girls have carried that name since the 1540s. I wondered in a more mystic way why a woman who, to me growing up, was the anti-thesis of a mother would carry the name of my most beloved spiritual mother. Growing up, especially beginning in adolescence, I was angry at Guadalupe. I couldn't understand how a mother could give her child away. Rather, her children since my sister and I were twins. As I grew older, I understood it intellectually and even agreed that it had been a good decision in my life to be raised and adopted by my great aunt and uncle who provided me with stability and love. Yet, despite my rational understanding, in my heart I was angry, resentful, and injured that my own mother had not wanted me. When I was 14, she contacted me through her sister, saying she wanted to meet me. I said no. I was too angry and injured. She was murdered when I was 21. I have regretted not meeting her my entire life. In my forties, I met her older sister. I hadn't known much about her life after she gave birth to us. I know she left town and moved to another border city. She couldn't have any more children. I learned from her sister that she led a tortured life, that she had been deeply hurt by her father and changed her last name to cut all ties with him. I learned that they had never found her killer. Her sister gave me letters that Guadalupe had written to her. In each letter, she asked about me and said she loved me. My heart began to open a bit. Guadalupe Fernandez, my mother One December 12, in my early fifties, I was invited to the home of a well-known writer. She had created a chapel on her land and installed a beautiful stained glass Virgen de Guadalupe there. I walked up to the altar in the chapel, carrying red roses to offer her and I prayed. In the silence of my prayer, I heard a voice. "I'm sorry. Forgive me." I knew it was Guadalupe. I stood with the words in my heart, eyes closed. As I left the chapel, I became nauseous. By the time I reached the next stop, the home of some friends, I was very sick and spent half an hour in the bathroom throwing up yellow, acidic bile. All the anger and hatred that I had carried for decades was expelled from my body. From that night onward, my heart cracked wide open to allow her in. The following day, I pulled out a photo of my mother that I kept in a drawer and put it with the other family photos. I told her that I loved her. I knew that La Guadalupana had healed my most profound hurt by showing me how to love my other Guadalupe, my 19 year old mother who never forgot me.

On December 12 of each year, I honor both my Guadalupes, my mothers. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022