|

I’m totally deaf in my right ear. It happened as a result of numerous tumors that grew inside my right ear over the course of years, destroying the small bones that allow us to hear. My otolaryngologist told me that the roots of my tumors and subsequent deafness must have started before I was 9 years old. Medicine people have often asked me, “What don’t you want to hear.” “What didn’t you want to hear as a child?” Honestly, I hate that question. I think most of us have things we don’t want to hear and for me, that question elicits fear and anxiety. Not wanting to hear resulted in one of my most significant interrupted stories dragging out until my sixties. So, this is a cautionary tale and a story of hope. My parents told me that I was adopted just as I was about to enter first grade, at the recommendation of my elementary school principal. I didn’t really understand what it meant but as I grew up, I began to hear stories about my birth mother. For most of my adolescence and teenagerhood, I felt numb and disinterested when I thought about her. When I gave birth to my son when I was 25, my anger came out. How could a mother leave her child? As a new mother, I couldn’t imagine. It took many years to heal my relationship with my birth mother, complicated by the fact that she died when I was 21 years old. Somehow, my birth father escaped my attention and my anger. I occasionally heard comments about him. “Dicen que tu papá era americano,” was the most common and the one that made me angriest. How could I have a White father? I was born in Juárez and I identified strongly as a mexicana, and later a Chicana. Looking back, I remember the times that my “authenticity” as a mexicana was questioned and the pain that this caused me. My aunt used to tell my mother that I was too agringada. Once, a stranger I met at a neighborhood tiendita argued with me about my identity, saying that I didn’t have the “face” of a Mexican. Being raised by a very white-skinned mother (to whom I was biologically related) allowed me not to question my own light skin or my features. Years passed. I learned more about my mother, especially when I met my birth aunt, her sister, around 2001. The day I met her in her long-time home in Arizona, she handed me a framed photo of my mother and a manila envelope with several photos in it. “Este es tu papá, she said. “This is your father. He loved your mother very much.” When I looked carefully at them, weeks after she’d given me the envelope, I noticed there were three men, not one. Two were very handsome Mexican-looking men. One had written a very romantic dedication to my mother, calling her “mi reina.” The third was a very young White man, a teenager probably. Could the young white man be my father? Could he be the “americano” that I had heard about in my youth? I laughed and put them away in a drawer where they stayed for years. I chose to believe that none of them were my father. Then about four years ago, I decided to do my DNA. I spit in the tube and sent it off to the lab not because I was thinking about who my father might be but because I wanted to know how Indigenous I was, what percent Native American my DNA was. After finally finding my spiritual community among Mexicans and Chicano people who returned to our roots in Mexico, I needed affirmation. I certainly understand how problematic this is…. But I felt I needed this. Some of my friends in academia make fun of DNA tests and it’s especially easy to do so if you look at DNA company commercials. One of my favorites features Kyle who thought he was German but turned out to be Scottish! Of course, and this is common sense, identity is much more complex than taking a DNA test and we can’t simply switch from lederhosen to a kilt, but DNA is an incredibly useful tool in bridging our interrupted stories. It helps answer questions for adopted people from “What ethnicity am I?” to “Who are my parents?” I remember the day my DNA results came in. I excitedly opened the link in the email. I was 2/3 European, with Irish being predominant. I sat there staring at the computer screen confused. European? Irish? Because I couldn’t believe it, I took another DNA test at another company. Two months later, the new results came in. They were more or less the same: Native American, Iberian, and Irish in roughly the same percentages but the European DNA was again roughly 2/3. I thought of all the ways the Irish had come to Mexico: during the US-Mexico War of 1846-48 with the famous San Patricios and with Irish migration to Mexico during to purchase mines during the Porfiriato. I knew that Chihuahua had the highest numbers of Irish migrants than any other state except for el Distrito Federal. I was trying to make sense of it, but I wasn’t listening. “Dicen que tu papá era americano.” Eventually, as a learned to navigate the DNA websites, I looked at my DNA relatives, those individuals who had also taken the DNA test and to whom I was related to biologically. The list was filled with people whose roots went back to Harlan County, Kentucky. What??? Early in the first couple of years, I wrote to relatives asking if they knew anything about a relative having lived in El Paso, on the border, but no one knew. Of course, I didn’t even know my father’s name. I could see that I was related to families with classic Kentucky last names: Brock, Lewis, Sizemore, Osborne, and Saylor. I was even related to the Fugates, the famous “blue” people of Kentucky who have a gene that produces blue skin of various hues. I studied Kentucky history and learned about the tri-racial Melungeons. I learned about the Cherokee who many of my relatives claim as their ancestors. I learned about the labor strikes in Harlan. Like a good historian, I attempted to put my DNA into historical context. I listened to blue grass music. I looked at photos of Appalachian families. I tried to feel connected. My DNA “family” were overwhelmingly kind. They spoke to their grandmothers and other elders in their families. They encouraged me that I would find out what I was looking for. Just recently, a DNA cousin from Kentucky wrote to me and said, “Welcome to the family.” Their kindness was very comforting yet, I was still confused and more lost than ever. This is a common Internet image of the Blue People of Kentucky. I don't yet have its source. About a year ago, a “new” DNA relative appeared and we were closely related. So closely related that, finally, I learned who my birth father was: an americano from Kentucky. My cousin Melinda Gould put her expertise in genealogy and DNA to work to make the genetic and genealogical connections. My birth father was a young man named Charles who had been stationed in El Paso in the 1950s but whose ancestors had lived in Kentucky for generations. For decades, I had refused to listen. By the time I could listen, everyone who knew anything in my maternal family about my paternal side were gone. Were it not for DNA testing, I may have never been forced to listen. I would not have begun to bridge the interrupted story of my birth father. I would not have found Charles. As I looked through the historical records, I found Charles listed as a small child living in a Harlan County mining town in 1940. The towns were known for their poverty and inadequate living conditions. Coal mining was one of the most dangerous occupations and working conditions were deplorable. It is no wonder that that in the 1930s, the mining camps were “Bloody Harlan,” where miners and unions clashed with mine owners and law enforcement. In a 1931 article, John Dos Passos wrote about the impoverished conditions of coal miners. One coalminer’s wife testified that her family of four barely managed to exist. My father’s family had not always lived in the mines. As I went back from census to census, tracing his father and mother, then his grandfather and grandmother, they were farmers. Earlier generations farmed in Laurel (home of Kentucky Fried Chicken) and Perry (think the “Dukes of Hazard”) going back to the early 19th century. Earlier, the family moved across N. and S. Carolina, eventually settling in Kentucky. In Alessandro Portelli’s They Say in Harlan County: An Oral History, one of the narrators says that sometimes, out of desperation, farmers came to mining camps to look for work, without a clue as to what mining entailed. “But they were glad to make a little money even under those conditions….” Said one narrator. Charles died about twenty years ago. I’ve tried to discretely contact his family—they have not responded. But it’s fine. I have the bridge I needed to heal the interrupted story. Finally, fifty years later I listened to what I didn’t want to know and I found my heart growing to welcome in all the new ancestors that I found.

0 Comments

A grainy 1924 photo of Felicitas from her local border crossing card. The story of Felicitas Leyva is one of the interrupted stories that wove itself throughout my childhood and remained with me into adulthood. I’ve never stopped thinking about her and, as the years have passed, I have felt a strong imperative to bridge the story of Felicitas and her husband, John Lucas. Training as a border historian has assisted me in this journey of recovery. As I’ve written previously, stories may be silenced, forgotten, hidden or apparently lost but they are simply interrupted, not destroyed. Their presence continues in our lives: in the way we view the world, in the way we look physically, in all the aspects that make us whole human beings. My father related fragments of the story of his tía Felicitas. He was a boy when she came to El Paso. He said his aunt moved to El Paso, worked as a maid in a brothel, met her husband John and married him. There was vague discussion of a child. For years, I searched for the documentary evidence and slowly, as I went through census records of both the United States and Mexico, birth and death records, and newspapers, her story began to appear. That’s how history is recovered—small bit by small bit until the story begins to unfold. Years ago, when I lived in Tucson, I stayed up to witness a meteor shower. Laying back on an outdoor lounger, I stared at the black sky. I saw only darkness and I was disappointed. But, I decided to be patient. Slowly, my eyes focused on one meteor streaming across the sky. Then another and another. Soon, I could see the shooting stars crisscrossing the sky. That’s how history is. It takes patience to finally see the bigger picture. In 1919, twenty-year-old Felicitas Leyva crossed the border from Chihuahua to Texas, bringing her four-year-old son Pascual Molina. During her relatively young life, she had moved many times, first from la Hacienda de Dolores in Chihuahua where she was born to Zaragoza, Durango where she married Gilberto Molina to El Paso, Texas and eventually to Ciudad Juárez where she died in 1948. Her family began their migration throughout the Mexican North before her birth as shown by the birth of her siblings in Durango, Chihuahua, and Coahuila. Sometimes we have the image of our ancestors living in a village or town for generations and that is true for many. For others, however, internal migration or transnational migration began generations ago. Felicitas’ early life was shaped by the Porfiriato and the changes occurring throughout the country. Along with countless other rural families, Felicitas’ family moved from place to place in the 1890s. The 31-year long rule of Porfirio Diaz pushed the poor to seek work on haciendas and in cities and internal migration within Mexico grew during Mexico’s so-called “modernization.” By the time Felicitas crossed the border into El Paso in 1919, she had moved many times. Felicitas was born during her family’s time at La Hacienda de Dolores, a colonial-era hacienda dating back to the early 16th century, located near present-day Jiménez, Chihuahua. Once a Jesuit property, by the mid-19th century Dolores was a “large estate with well irrigated and cultivated fields,” according to A. Wislizenus, a physician with Colonel Doniphan’s expedition in 1846-47. Throughout the 19th century, government reports mention attacks on the Hacienda by “indios bárbaros del norte.” By the time of Felicitas’ birth in 1899, the area was known for its textile manufacturing and its flour mills powered by steam engines. In 1910, the day before the official beginning of the Mexican Revolution, Pascual Orozco and his troops, comprised of Maderistas and anarchistas, attacked the hacienda and he was named head of the Maderistas in the region. Felicitas was 11 years old. In the succeeding years, as Felicitas entered adolescence, the area around Dolores and Jiménez was the site of much Revolutionary activity. In later years, Felicitas’ siblings and nephew would proudly say that her father Quirino Leyva provided horses to Pancho Villa. Felicitas' father, Quirino Leyva. On December 29, 1914, at age fifteen, Felicitas married Gilberto Molina in Tlahualilo de Zaragoza, Durango and five months later gave birth to a son, Pascual. Tlahualilo de Zaragoza, part of la Comarca Lagunera, was originally inhabited by Indigenous peoples such as the Rarámuri and the Tepehuanes. In 1851, two Spaniards founded the first 19th century settlement in the area. By the late 19th century, it began to produce agricultural goods and in 1891, the first cotton was harvested. In 1897 a railroad was built to connect Tlahualilo to Eagle Pass, Texas. At the time the Mexican Revolution broke out, Tlahualilo was a thriving agricultural area, connected to the United States via the Ferrocarril Internacional, with ties to both Eagle Pass and El Paso. Pancho Villa was a frequent visitor to Tlahualilo, making his first grand entrance to the town in 1912, an act that the town still celebrates, and it was one of the haciendas he asked for when negotiating the end to fighting in 1920. It played a significant role during the Revolution and throughout the Spring and Summer of 1914, Villa sent significant number of troops to Tlahualilo in order to stop the federal troops from taking control of Torreon. I wondered how and why Felicitas moved from Dolores to Tlahualilo to marry Gilberto so I explored the relationship between the two places in the context of the Revolution in 1914 and 1915. In 1914, Villa controlled the state of Chihuahua. He was the provisional governor, in fact, and at the height of his influence and popularity. In 1914 and 1915, Villistas were in Jiménez (la Hacienda de Dolores) and Tlahualilo. With 50,000 men in la División del Norte, perhaps Gilberto was a soldier. One of the most common stories about troops entering a town relates to the fear it struck in the hearts of girls, women, and their parents. Troops kidnapped women, raped them, and sometimes their families never saw them again. The stories that relate the ways in which families protected the girls of the family when troops (either federal or revolutionary) arrived show their ingenuity fueled by fear. Perhaps one of the most terrifying accounts I’ve discovered through my research was the story related by Manuel Servín Massieu in an oral history published in 1985 by the Instituto Nacional del Antropología e Historia. Servín recalled the gripping stories which his elderly relative Celedonia often told him of her youth in Zacatecas during the Revolution. One day in the fall of 1916, she and several other young women were drawing water from a well when a commotion started. Soon, several of their parents appeared, "todos pálidos y asustados,” pale and scared, because Villistas were on their way to the rancho. To hide the girls, the parents made them climb down the wooden ladder which led to the interior of the well. Celedonia remembered that the well was so deep that a stone thrown into the well would take ten minutes to hit water. Afraid of falling into the dark depths of the well and afraid to leave because of the Villistas (who their elders had warned would "steal them and take them by force" or "would kill them and throw them to the side of the road"), the girls hid "con la muerte abajo y con la muerte arriba.” If they came out of the well, they could be killed. If they fell into the depths of the well while hiding, they would drown. It was indeed a case of “death below and death above.” After throwing them some shawls and a few tortillas, their parents covered the mouth of the well with boards and dirt. Such measures evidence the terror with which parents and girls viewed the coming of “la bola." We often romanticize the Mexican Revolution and the role of the soldadera, La Adelita, but the reality for many girls and women was horrific. Was Felicitas taken by Gilberto as part of the "spoils of war," as were so many women? Did she go willingly, following him from Chihuahua to Durango where they married in December of 1914? We probably will never know but we do know well that the atmosphere for women was one of fear, constant threats, and trauma. She was four months pregnant at the time of their marriage in Tlahualilo. Famous photo of Mexican Revolution federal soldier with his wife and child. No documentary evidence tells us what happened with Gilberto after the birth of their son. Was he killed? Historians estimate that 1 million Mexicans died during the Revolution so it is a possibility. The flu epidemic of 1918 killed another 300,000 Mexicans. Did the terrible illness take him? Is that why Felicitas came to the United States the following year? Perhaps Gilberto escaped to the US-side of the border, took another name, started another family and lived out his life here. We simply don’t know.

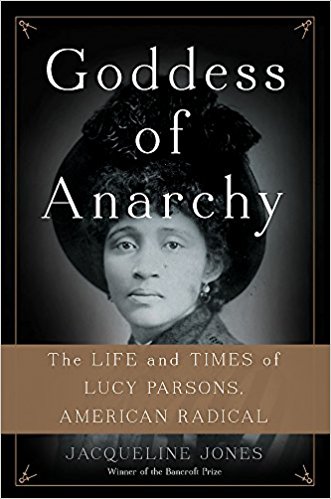

We know that Felicitas reported to the census enumerator that she crossed the border in 1919. We know that she met John Lucas that year and married him in 1920. In 1924, Felicitas was living in Juárez and acquired a local border crossing card. She had dropped Leyva and took on her mother’s maiden name, Fierro. By1930, both Felicitas and John were married to different people. John was married to Lola B. Lucas and still living in El Paso. The Census recorded that John’s household included his son, John Jr. Felicitas was married to Saturnino Chasco and living in Juárez with her husband and her son, Pascual. There is a twist to the story, however. A 1921 Texas birth certificate shows that John Jr. was the son of Felicitas (whose color was listed as “Spanish”)and John Sr. (whose color was listed as “Negro”). As Felicitas returned to Mexico, relocating to Ciudad Juárez with her older son Pascual sometime before 1924, John Jr., or Johnny as he was called, stayed in El Paso with his father and eventually his step mother, Lola. Finding the birth certificate punched me in my gut. Without the presence of this birth certificate, it would be easy to assume that Lola was his biological mother. They are listed in the federal census together and in John Sr.’s obituary. My first thought was that Felicitas was not allowed to keep her son. My second thought was that Felicitas did not want to return to Mexico with a Black son. Either scenario is heart-breaking. Did John Jr. know he had a brother on the other side of the border, Pascual? Did he see his birth mother? Did she want to see him? How could a mother leave her child? These are the same questions I had asked about myself and my birth mother and my sister through much of my life and that’s how interrupted stories work. The fragmented stories that haunt us, the ones we can’t let go of even if we have only fragmentary knowledge, may be the very ones that speak directly to our lives. Just as I came to understand and forgive my biological mother Guadalupe for leaving me, I believe that Felicitas also needs understanding and compassion. Bridging the interrupted stories in our families allows us to acknowledge, forgive, and love the generations before in order to heal ourselves and the generations to come. Bridging the ruptured stories allows us to understand our connections among each other, both in tragedy and hope. Finding John Lucas and Felicitas Leyva permitted me to see how two very different individuals, divided by nationality and race, came together amidst their deeply traumatic experiences, seeking a better life and having hope for the future. Last May Day (2017) I wrote a post about Lucy Gonzalez Parsons, the radial labor organizer and anarchist. In that post I wrote, "Lucy Gonzalez Parsons is an enigma. Her early life is not documented and she often told different stories about her early life. While some say she was born into slavery, she denied any African American heritage. Some believe her father was was a Muscogee man named John Waller and that her mother was a Mexican woman named Marie del Gather. She said she was Mexican and Native American and had been born in Texas. Sometimes she said she was born in Virginia. After the Civil War, she may have been married to a freedman named Oliver Gaithings. We don't really know. What we do know is that she was an influential, radical, labor activist, anarchist, and writer who is an important part of the May Day story and the history of the US labor movement." Well, now we know.... at least we know more. I'm reading Goddess of Anarchy by esteemed historian Jacqueline Jones. She's traced Parson's birth to an enslaved woman in Virginia. Like many others, she and her mother were brought to Texas by their owner in order to take advantage of the cheap land. Disappointing to those of us who claimed her as Mexican but even more disappointing to me was that she rejected her own roots, creating the fictional identity of a Mexican-Native American woman rather than the reality of her being a Black woman. It makes sense, however, in the context of post-Civil War Texas.

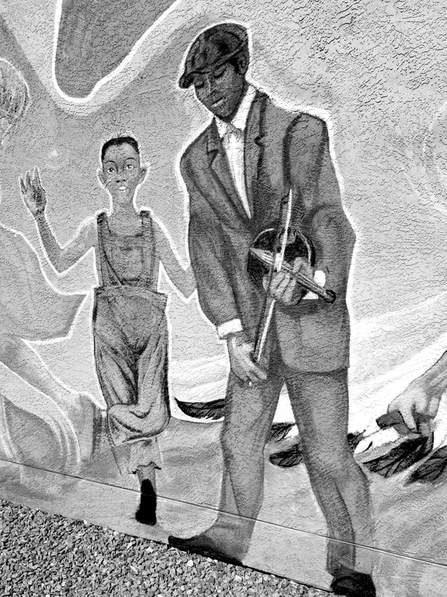

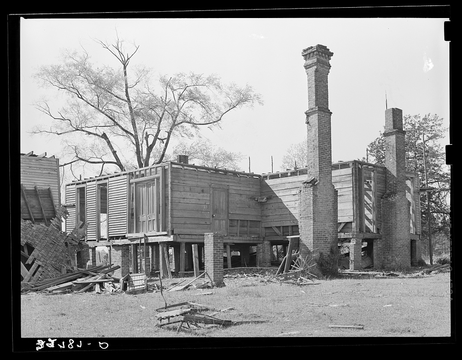

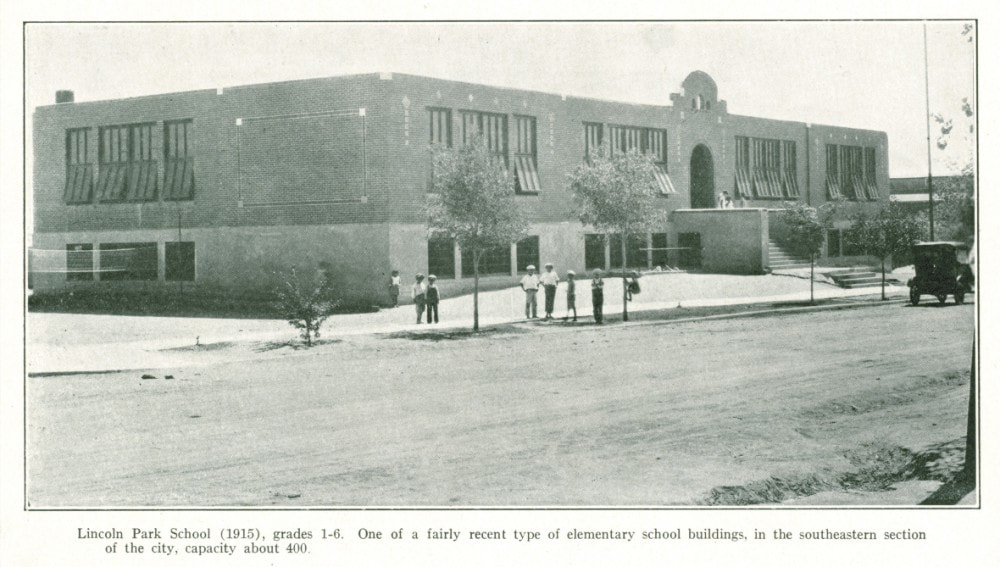

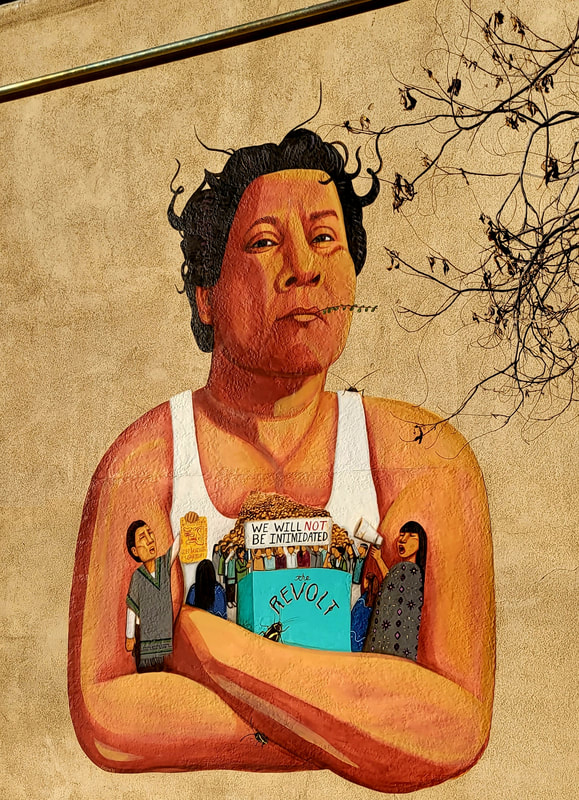

Goddess of Anarchy is a truly fascinating and myth-busting book that looks at Lucy Parson's very complex identity and life. It is meticulously researched and beautifully written. If you want to learn more about Lucy Parsons, pick up a copy of this new book soon! B & W photo of mural at Chamizal National Memorial commemorating the multiracial community of El Paso. There are stories that live on in our families as fragments, as small details shared casually in the midst of conversation. We must never underestimate their power, however, or undervalue their place in our familial healing. Bringing these interrupted stories to light and creating the bridge that connects the past to the present is part of the recovery of our whole selves. The consequences of the stories embed themselves in our physical make up-- our skin color, our hair texture, or our gait. They survive in us spiritually, mentally, emotionally, and physically. Creating the bridge over the rupture allows us to understand ourselves and our ancestors, to acknowledge them and to heal. Exploring the life and times of John Lucas, my great aunt's husband, is one of the ruptured stories that wove itself throughout my childhood. Looking back on my growing up, especially now as a scholar of borderlands history, I am not surprised at the ways in which race and skin color played themselves out within the confines of my small, nuclear family. While the two, race and skin color, are not synonymous, they are linked. Like so many other Mexicano families, we were of varying shades. My father, of Rarámuri descent, was so dark that during his time in West Virginia during World War II, he was perceived as “colored” and was not served in restaurants. My mama, on the other hand, was so white-skinned that White people didn’t think she was Mexican. As a consequence, she witnessed countless denigrating conversations against our people while she was in public. Believing her to be another white woman, white women felt free to degrade Mexicans in front of her. This is a classic Mexican American story. So, too, are the stories of families who are relieved when their children are born with whiter skin. “Que bonita. ¡Tan blanquita!” How many of us were told to stay out of the sun lest we get too prietas? The insidious colorism within our people is without question. The colonial-era casta paintings, with their endless combinations of racial intermixture and the subsequent range of skin colors, have nothing on us! When my mama and daddy argued, they hurled racialized code words against each other like vinagrón, a black scorpion-looking arachnid that used to be common in our desert community. My father would respond to being called a vinagrón by calling her un niño de la tierra, a white cricket-looking insect with a powerful bite. Sometimes, in the heat of a fight, my mama would add, “Tu tía se casó con un hombre negro!” as if it were the height of insult. And to her, who cherished white skin, it was. Despite her attempts to anger him, this mention of his aunt often de-escalated the fight as my daddy sighed and stopped to tell me about his tía Felicitas. I remember his voice would soften as he recounted the difficult lives that the women in his family faced due to being impoverished, Mexican women. De mulato y mestiza, produce mulato, es torna atrás (ca 1715). Painting by Juan Rodriguez Juárez. During the colonial period, every conceivable intermixture of people was categorized although in day-to-day life, only a select few categories were actually used. The fragments that my father shared with me of his aunt's story were few. Felicitas had come to El Paso during the Mexican Revolution, found work as a maid in a brothel, met John Lucas and married him. That’s all I knew yet I remained intrigued with tía Felicitas my whole life. Could I find Felicitas, a poor campesina born somewhere in Northern Mexico during the Porfiriato who migrated across the border during the chaos of the Mexican Revolution? Could I find her husband John Lucas when I knew almost nothing about him? For years, I searched archives and historical documents for clues about Felicitas and John. Finally, one day four years ago, I found mention of them in a tiny announcement in the January 29, 1920 issue of the El Paso Herald. There, next to an ad for the “calyx skirt” and just below an article pitting the intelligence of brunettes against that of blondes, was an article, “El Pasoans wed in Las Cruces.” The couple married in Las Cruces, no doubt, to escape Texas’ anti-miscegenation law. Despite our treatment as second-class citizens, Mexican Americans were legally defined as white. In the early 20th century, Las Cruces, New Mexico provided opportunities to Black El Pasoans that were denied by Texas law, including the right to marry a “white” woman and get an education at the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts. In the early twentieth century, as Felicitas and John wed, Black men and Mexican women created intimate relationships while facing criticism and threats from the judicial system. The classification of Mexican and Mexican American women as “white” made Mexican-Black marriages illegal in many states, including Texas. In her 2017 book Porous Borders: Multiracial Migrations and the Law in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands, historian Julian Lim (PhD, JD) writes about the precarious situation of interracial marriages between Black men and Mexican women in early El Paso. Although El Paso was certainly a more accepting city than other Texas cities, white supremacy still took root and flourished. Lim writes about a group of Black men and Mexican women who were arrested as “miscegenationists” in 1893. Lim cites an El Paso newspaper’s warning following their arrests: they were “only the inauguration of a general movement against all violators of the laws against miscegenation, adultery, and fornication.” It didn’t matter that some of the couples were married in places where they could marry (Mexico, for example). Their marriage was still against Texas law. As one observer wrote, the men were in trouble for marrying their color, but not their race. The day following the arrests, numerous Black families moved across the border to Ciudad Juárez. (See chapter 2 in Porous Borders for more on this story.) A Texas law passed just five years before Felicitas and John married made intermarriage a criminal offense punishable by two to five years in the penitentiary. A 1925 Miscegenation law declared interracial marriage a felony and nullified interracial marriages even if they occurred in a place where these marriages were legal. Despite their efforts, Felicitas and John found themselves breaking the law through their marital relationship. Texas' anti-miscegenation law remained on the books until 1967. The complexity of Black-Mexican relations continued into the 1930s and beyond. When El Paso's city registrar, announced in 1936 that city documents would designate Mexican Americans as "colored" in birth and death records, it created a strong defensive reaction from both Mexican Americans in El Paso and Mexicans in Juárez. A letter to the editor from J. Hamilton Price that fall stated that Mexican Americans had no reason to be outraged. He described the many marriages between Black men and Mexican women, going so far as to say that "negro-burros" was the common name for their offspring. (See Beyond Black and White.) It was within this contradiction between the existence of inter-racial marriages and intimate relationships contrasted with the deep anti-Black sentiments of many Mexican Americans that my great aunt Felicitas and John decided to marry. Despite facing possible criminal charges for their relationship, the 1920 Federal Census showed them living in El Paso in an area with a majority ethnic Mexican population in addition to several Black families. Felicitas and “Juan,” as he was called in the census were the only inter-racial couple. Felicitas’ son, five-year-old Pascual Molina, lived with them. As I poured over census records, city directories, and newspapers, the life and times of John Lucas drew me in. El Paso's Black population has always been small-- 2 to 3%. The early history of the city's Black community was intertwined with that of the Mexican immigrant community. The city's first Catholic Church for Spanish-speaking parishioners, Sagrado Corazon, and the first African American church, the Second Baptist Church, are within blocks of each other in El Segundo Barrio. What brought African Americans to this predominantly Mexican West Texas town? Lim argues that El Paso represented a gateway to new freedoms for the Black, Mexican, and Chinese people who migrated there. For African Americans, it was a way to escape the oppressiveness of Jim Crow and the increasingly virulent white supremacy of the South. As I learned more about John, it made more and more sense. Migrating to the border from East Texas, it seemed that John was indeed escaping the violence of Jim Crow. Ruins of an old plantation in Marshall, Texas by documentary photographer Russell Lee, 1939. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. John Lucas' roots in the East Texas town of Marshall went back to his grandparent's generation in the decade before the Civil War. Historian Jacqueline Jones writes that in the period before the Civil War, Texas was a “perennial magnet for southern planters seeking to take advantage of cheap fertile land suitable for cotton cultivation the eastern and central part of the state…” (Goddess of Anarchy p.7) Indeed, during the Civil War thousands of slaves made what Jones calls the “brutal wartime ‘middle passage’ from Virginia to Central Texas.” (xiii) John Lucas’ grandparents, Lucion and Ann, born respectively in Virginia and Mississippi in the 1830s, made that forced relocation to Texas sometime by 1855 when their first daughter Nancy was born. Their son, Willis, was born in Marshall in 1856, four years before the Civil War broke out. During Willis’ early childhood, Marshall was radically anti-union and pro-slavery. Victoria White, John's mother, was also born in Marshall in the 1850s. I have little doubt that Willis’ grandparents and parents were enslaved. There would be no other reason for Black people to come to Marshall in the 1850s. By 1860, when John's grandparents were children, Harrison county where Marshall is located, had more enslaved people than any other county in Texas, making it the richest county in Texas and the fifth largest city. White workers complained that the presence of so many skilled enslaved people was creating competition and taking their jobs away. During the Civil War, Marshall became an important Confederate city. Following the end of the Civil War, during Reconstruction, the situation of Marshall’s Black population eased some and it was during this period that 19-year-old Willis married 15-year-old Victoria White. The couple had seven children, including John. John Lucas was born in June 1883, the same year as well-known civil rights leader Dr. Lawrence Nixon who challenged Texas’ white only Democratic primary. By the time Lucas and Nixon were born, Marshall was long “redeemed” from Republican control and the former powerful antebellum families were in power again. White supremacy flourished in Marshall during John’s childhood and young adulthood. In 1903, when John was twenty-years old, the Los Angeles Herald reported that a race war had broken out in Marshall. Following the arrest of “a negro,” the newspaper reported that a group of Black men helped him escape, ambushing the Constable and killing him. By 6 p.m. that evening, 600 White men were armed and ready for revenge. They took a Black prisoner from the jail, Wallace Davis, and lynched him. The report warned that every Black had to leave Marshall or face a “war of extermination.” In the years before John came to El Paso, there were at least ten other lynchings in Marshall, all men, all Black. They faced torturous treatment at the hands of White mobs, including unspeakable acts of mutilation. In April 1909 alone, four Black men were lynched over the course of two days. When Lawrence Nixon witnessed a lynching in front of his medical office in Marshall, he decided to leave, eventually coming to El Paso a few years earlier than John. The racial antagonism and violence had to be unbearable for Marshall's Black community. As a young man, John had options-- he could leave East Texas and seek a better life. John and Lola eventually lived across the street from this school. Their home was demolished and is now part of Lincoln Park. It is unclear where John lived between 1910 and the first evidence of his residence in El Paso in 1917. He doesn’t appear in Marshall in the 1910 Census although there is a John Lucas married to Palace Lucas nearby in 1910, both listed as mulatto. It could be them or not. By 1915, John’s brother Charles was living in El Paso, working as a porter, and living on Palm Street on the same block where we found Felicitas and John living five years later. Perhaps Charles came earlier and called for his brother to join him as racial violence in their home town escalated. John was listed as a boilermaker helper in 1917, an occupation he would hold for decades. As a skilled craftsman, John was part of the legacy of the enslaved men of Marshall who worked in skilled occupations such as mechanics. John retired with a railroad pension under the last name “Lacy,” a name he father had also used, for reasons unknown. Just a few years after arriving in El Paso, John met Felicitas. In 1919, Felicitas Leyva crossed the border into El Paso with her four-year-old son, met John, and they married in 1920. When I looked at the 1920 Census, reading between the lines, it seems that the Census enumerator spoke with Felicitas. She did not know English and the notation of John as “Juan” gives us a clue. While the birthplace of other US-born residents listed on the Census form lists their state, John’s birthplace is listed as “United States.” It seems unlikely that he would not say Texas. I wonder how much they knew about each other? Did John speak Spanish? How did they make a life together, having crossed so many borders, geopolitical and social? Sometime between 1920 and 1930, Felicitas disappeared from John's life. There is no documentation of divorce because by then their marriage had been declared null by Texas law. In the 1930 Census, 45-year-old John appears married to 38-year-old Lola Lucas with an 8-year-old son, John, Jr. They, like Felicitas and John, lived surrounded by Mexican neighbors. John and Lola remained married until John’s death in 1959. John was buried in Concordia Cemetery in February 1959, survived by Lola, John Jr, and three grandchildren. Almost a century after the controversial marriage of my great aunt Felicitas and John, my Afro-Mexican grandchildren remind me that these histories matter. Little by little, I am building bridges across the chasms in my family history, connecting the past with the present and starting to heal. In addition to Julian Lim, Porous Borders, and Jacqueline Jones, Goddess of Anarchy, see: "Good Neighbors and White Mexicans: Constructing Race and Nation on the Mexico-U.S. Border" Author(s): Mark Overmyer-Velázquez Source: Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Fall 2013), pp. 5-34 and Beyond Black and white: Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in the U.S. South and Southwest.Stephanie Cole and Alison M. Parker, editors. Texas A & M Press, 2003. There are stories. There are stories that are passed on from generation to generation. And there are stories that are silenced and forgotten. There are people who carry the stories consciously and those who don't care. Sometimes the stories survive in the most breathtaking of details and others barely exist as fragments and glimpses. They can teach us hope or they can explode with trauma. Years ago, I studied with writer Sharon Bridgforth whose innovative work is recognized nationally. In an early class, she asked the question, "Who are your people?" For me, a newly-minted PhD in history, a carrier of family stories, a fronteriza born on one side and raised on the other, and still carrying the uncertainty and the ambiguity of adoption, the question took away my breath. Where did I fit in? Did I belong? Who were my people? I knew the answer lay in the stories I knew and especially the ones that I didn't know. My healing lay in bridging the interrupted story. I use the word “interrupted” because I know that silencing, hiding, forced forgetting or all the other ways we lose our histories don’t put an end to the stories. They are interrupted, not destroyed. Their presence continues in the lives of generation after generation even if the details of the stories are lost. In Spanish, history and story are represented by the same word--historia. If you trace the word historia back far enough past the 15th century Middle English to 12th c. French to Latin all the way back to the 6,000 year-old Proto-Indo European language root, we find that historia grew from the verb “to see.” What happens if we can no longer “see” our history and our stories. What happens if they are interrupted by fear or shame or forced silencing? If we cannot bear witness to our histories, how can we heal? In Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot explores how power centers certain voices and represses others, most often invisibly. “History is the fruit of power, but power itself is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous. The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots,” writes Trouillot in his preface. It is one of my favorite quotes from this compelling book. Year after year, my undergraduate students sit in our classroom stunned at some part of their own history that they did not know and ask “Why were we never taught this?” I ask them to answer their own question. Eventually, they know that it has to do with control and power. Keeping our histories and our stories hidden from us is a way to restrict our deepest knowledge of ourselves. It is a way to limit our understanding of the strategies that our ancestors used to survive. It not only keeps us from the hope embedded in the stories, it often makes the sources of our traumas invisible. Trouillot traces the creation of silence in the production of history to four crucial moments: the making of the sources, the making of the archives, the making of the narrative, and the decision regarding what is the significance of this history. Clearly, in the discipline of history there are structures that create silences. So too in our everyday lives. Some stories are too dangerous to share. We need look only at the ways that violence is used to silence people in their personal lives. This violence ranges from threats of physical violence to loss of employment to threats of displacement. Michel-Rolph Trouillot As an oral historian, I have seen people self-censor themselves to protect themselves or their families. In a 2016 oral history that I conducted with Jesús Zamora (born in the 1940s), he talked about his grandfather’s dying words. “Don’t tell them who you are.” His grandfather who came of age at a time when the Mexican government paid for “Apache scalps” and the US government declared all-out war against Native peoples, his abuelito understood the danger of telling others that he was Native. Mr. Zamora, a Vietnam vet, now says that he can be who he really is without fear and works with Native American soldiers through a special program at the nearby military installation.

Over a decade and a half ago as I worked with high schools students in Socorro, east of El Paso, a young woman discovered that her great-grandmother had been raped as a young woman during the Mexican Revolution. The story has been kept alive from great-grandmother to grandmother to mother but they had not wanted her to know because they wanted to protect her from this terrible family story. When they finally shared it with her because of our history project, she was both relieved to know this history that had shaped her family but also grieved over her great-grandmother’s experiences. Sometimes stories are silenced out of shame or embarrassment. One day, two decades ago as I lectured about Emma Tenayuca, a fierce labor organizer in San Antonio whose work in the 1930s brought her national (and often negative) attention, one of my students approached me after class. She hesitantly told me that she was related to Tenayuca but that her family didn’t want anyone to know because Tenayuca had been a member of the Communist Party and they were embarrassed. Later, in this series I will share a story that my own family tried to silence because of their embarrassment that my great-aunt Felicitas Leyva had married a Black man, John Lucas, in the early twentieth century during Jim Crow. It is one of the interrupted stories that I have worked to bridge. As an educator, I’ve seen this interrupting happen over and over again. Families try to keep the suffering and the trauma away from their children believing that not knowing will protect them. The treacherous thing about the interrupted story is that, while the story itself may be invisible, its consequences are not. Our physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual traumas leave us unbalanced, confused, and suffering. We may think of our emotions, thoughts, and behaviors “irrational” without knowing their roots. While uncovering our stories helps us understand ourselves, just knowing isn’t enough to heal us. It is the beginning, however. The first step to healing an interrupted story is to create a bridge over the rupture of the story. Sometimes this comes in the form of uncovering more details, fleshing out the history. As a historian, research is often my form of bridging. Bridging can come with deep listening, both to our elders and to ourselves. What if we cannot recover the historical facts of a family story? I often think that the growing popularity of DNA testing and genealogy is actually rooted in our efforts to bridge these interrupted stories. (In the US, genealogy is second as a “hobby” only to gardening.) As a spiritual person, prayer and meditation and calling out to our ancestors also allows me to create a bridge. We all need healing. In the following weeks, FierceFronteriza will present a series of posts on interrupted stories and bridging the rupture. I invite you to consider what stories need bridging in your own life. This post was originally published a year ago today, March 9, 2017. I've updated it with new images and new comments.  Like other holidays, the radical roots of International Women's Day have been forgotten by most people. While community organizers, activists, and historians remember, most Americans do not. Spurred on by the horrors of the current administration, a "Day without a Woman" was organized for today. Trump announced he has "tremendous respect" for the roles women play in society. Google honored 13 women, including Ida B. Wells and Frida Kahlo. [Update: There was no "Day Without a Woman" this year but Trump's 2018 International Women's Day statement continued to boast about his administration's respect and work on behalf of women: "As we mark International Women's Day, we remain committed to the worthwhile mission of enhancing women's leadership in the world and building a stronger America for all." Of course we know this is in direct opposition to the truth of what has happened in the past year.] Today, I want to remember the radical origins of International Women's Day. Aftermath of the shirtwaist fire, NYC, 1909 The industrial revolution was made possible by the work of enslaved people in the South and poor, often immigrant, people in the North. Textile and garment factories sought immigrant workers, including children and women whom they could pay less in order to make a profit. Working conditions were horrendous. In 1908, girls and women in New York City went on strike demanding higher wages. At the time, they were earning $3 per day. In 1909, the Socialist Party called for a commemoration of the strike and the first Women's Day was held in February 1909. In the succeeding years, the day was used to protest war as well. The day quickly become international as women organized both in the United States and Europe. The first years of the 20th century were filled with women and girls struggling for better working conditions. In 1903, organizers created the Women's Trade Association. In 1909, women garment workers organized the "Uprising of the 20,000," a successful strike that lasted almost four months. In 1912, the "Bread and Roses Strike" in Lawrence, Massachusetts brought over 20,000 picketers to the streets. The federal government responded to this growing organizing by women and men, many who were immigrants. In 1914, thirteen women and children and seven men were killed during a miners strike, "The Ludlow Massacre," in Colorado. In 1918, during WWI, the leadership of the radical Industrial Workers of the World were jailed in federal prisons, charged with disloyalty to the United States. The roots of International Women's Day are in the radical work of women and girls fighting for better wages and working conditions. They are in the early peace movement. They are in the courage of women willing to risk everything. For millions of women around the globe, little has changed. Women garment workers are still forced to work in terrible conditions with little-- and sometimes no- pay. Sweatshops in China, Bangladesh, and the United States continue to produce clothing for us at the expense of the health and well-being of women. [Update: Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing reports the global production of garments is in the control of relatively few corporations and that a shift has occurred from factories to home work, which is cheaper for the employers who don't have to pay overhead. For more information see the WIEGO website.] Tomorrow, when International Women's Day is over, what will you do to improve the lives of women? Left to right: 1910 Chicago garment workers strike; May Chen with the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union in 1982;"Children of Lawrence, MA strikers sent to live with sympathizers in New York City during the work stoppage 1912 news photo, ex-Bain News Service

|

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

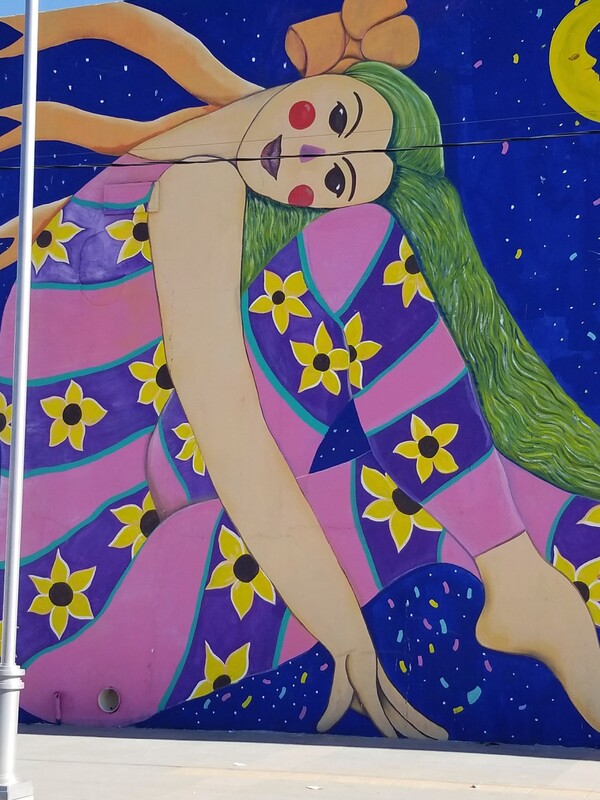

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022