|

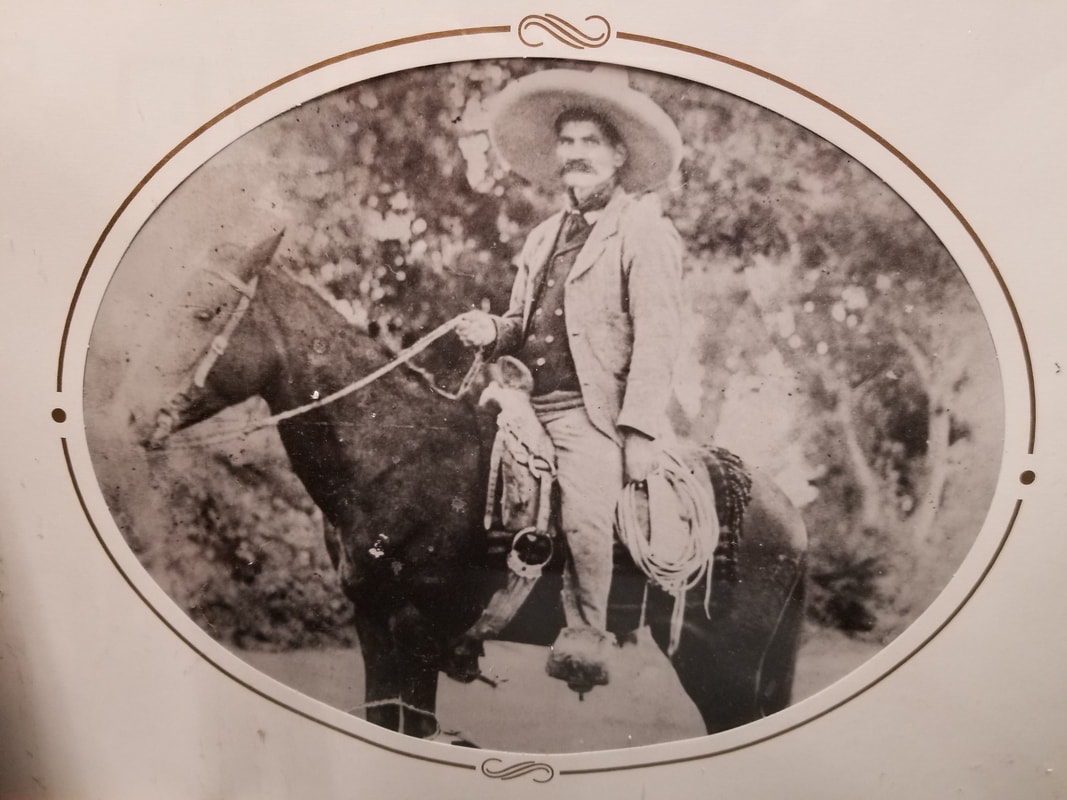

A grainy 1924 photo of Felicitas from her local border crossing card. The story of Felicitas Leyva is one of the interrupted stories that wove itself throughout my childhood and remained with me into adulthood. I’ve never stopped thinking about her and, as the years have passed, I have felt a strong imperative to bridge the story of Felicitas and her husband, John Lucas. Training as a border historian has assisted me in this journey of recovery. As I’ve written previously, stories may be silenced, forgotten, hidden or apparently lost but they are simply interrupted, not destroyed. Their presence continues in our lives: in the way we view the world, in the way we look physically, in all the aspects that make us whole human beings. My father related fragments of the story of his tía Felicitas. He was a boy when she came to El Paso. He said his aunt moved to El Paso, worked as a maid in a brothel, met her husband John and married him. There was vague discussion of a child. For years, I searched for the documentary evidence and slowly, as I went through census records of both the United States and Mexico, birth and death records, and newspapers, her story began to appear. That’s how history is recovered—small bit by small bit until the story begins to unfold. Years ago, when I lived in Tucson, I stayed up to witness a meteor shower. Laying back on an outdoor lounger, I stared at the black sky. I saw only darkness and I was disappointed. But, I decided to be patient. Slowly, my eyes focused on one meteor streaming across the sky. Then another and another. Soon, I could see the shooting stars crisscrossing the sky. That’s how history is. It takes patience to finally see the bigger picture. In 1919, twenty-year-old Felicitas Leyva crossed the border from Chihuahua to Texas, bringing her four-year-old son Pascual Molina. During her relatively young life, she had moved many times, first from la Hacienda de Dolores in Chihuahua where she was born to Zaragoza, Durango where she married Gilberto Molina to El Paso, Texas and eventually to Ciudad Juárez where she died in 1948. Her family began their migration throughout the Mexican North before her birth as shown by the birth of her siblings in Durango, Chihuahua, and Coahuila. Sometimes we have the image of our ancestors living in a village or town for generations and that is true for many. For others, however, internal migration or transnational migration began generations ago. Felicitas’ early life was shaped by the Porfiriato and the changes occurring throughout the country. Along with countless other rural families, Felicitas’ family moved from place to place in the 1890s. The 31-year long rule of Porfirio Diaz pushed the poor to seek work on haciendas and in cities and internal migration within Mexico grew during Mexico’s so-called “modernization.” By the time Felicitas crossed the border into El Paso in 1919, she had moved many times. Felicitas was born during her family’s time at La Hacienda de Dolores, a colonial-era hacienda dating back to the early 16th century, located near present-day Jiménez, Chihuahua. Once a Jesuit property, by the mid-19th century Dolores was a “large estate with well irrigated and cultivated fields,” according to A. Wislizenus, a physician with Colonel Doniphan’s expedition in 1846-47. Throughout the 19th century, government reports mention attacks on the Hacienda by “indios bárbaros del norte.” By the time of Felicitas’ birth in 1899, the area was known for its textile manufacturing and its flour mills powered by steam engines. In 1910, the day before the official beginning of the Mexican Revolution, Pascual Orozco and his troops, comprised of Maderistas and anarchistas, attacked the hacienda and he was named head of the Maderistas in the region. Felicitas was 11 years old. In the succeeding years, as Felicitas entered adolescence, the area around Dolores and Jiménez was the site of much Revolutionary activity. In later years, Felicitas’ siblings and nephew would proudly say that her father Quirino Leyva provided horses to Pancho Villa. Felicitas' father, Quirino Leyva. On December 29, 1914, at age fifteen, Felicitas married Gilberto Molina in Tlahualilo de Zaragoza, Durango and five months later gave birth to a son, Pascual. Tlahualilo de Zaragoza, part of la Comarca Lagunera, was originally inhabited by Indigenous peoples such as the Rarámuri and the Tepehuanes. In 1851, two Spaniards founded the first 19th century settlement in the area. By the late 19th century, it began to produce agricultural goods and in 1891, the first cotton was harvested. In 1897 a railroad was built to connect Tlahualilo to Eagle Pass, Texas. At the time the Mexican Revolution broke out, Tlahualilo was a thriving agricultural area, connected to the United States via the Ferrocarril Internacional, with ties to both Eagle Pass and El Paso. Pancho Villa was a frequent visitor to Tlahualilo, making his first grand entrance to the town in 1912, an act that the town still celebrates, and it was one of the haciendas he asked for when negotiating the end to fighting in 1920. It played a significant role during the Revolution and throughout the Spring and Summer of 1914, Villa sent significant number of troops to Tlahualilo in order to stop the federal troops from taking control of Torreon. I wondered how and why Felicitas moved from Dolores to Tlahualilo to marry Gilberto so I explored the relationship between the two places in the context of the Revolution in 1914 and 1915. In 1914, Villa controlled the state of Chihuahua. He was the provisional governor, in fact, and at the height of his influence and popularity. In 1914 and 1915, Villistas were in Jiménez (la Hacienda de Dolores) and Tlahualilo. With 50,000 men in la División del Norte, perhaps Gilberto was a soldier. One of the most common stories about troops entering a town relates to the fear it struck in the hearts of girls, women, and their parents. Troops kidnapped women, raped them, and sometimes their families never saw them again. The stories that relate the ways in which families protected the girls of the family when troops (either federal or revolutionary) arrived show their ingenuity fueled by fear. Perhaps one of the most terrifying accounts I’ve discovered through my research was the story related by Manuel Servín Massieu in an oral history published in 1985 by the Instituto Nacional del Antropología e Historia. Servín recalled the gripping stories which his elderly relative Celedonia often told him of her youth in Zacatecas during the Revolution. One day in the fall of 1916, she and several other young women were drawing water from a well when a commotion started. Soon, several of their parents appeared, "todos pálidos y asustados,” pale and scared, because Villistas were on their way to the rancho. To hide the girls, the parents made them climb down the wooden ladder which led to the interior of the well. Celedonia remembered that the well was so deep that a stone thrown into the well would take ten minutes to hit water. Afraid of falling into the dark depths of the well and afraid to leave because of the Villistas (who their elders had warned would "steal them and take them by force" or "would kill them and throw them to the side of the road"), the girls hid "con la muerte abajo y con la muerte arriba.” If they came out of the well, they could be killed. If they fell into the depths of the well while hiding, they would drown. It was indeed a case of “death below and death above.” After throwing them some shawls and a few tortillas, their parents covered the mouth of the well with boards and dirt. Such measures evidence the terror with which parents and girls viewed the coming of “la bola." We often romanticize the Mexican Revolution and the role of the soldadera, La Adelita, but the reality for many girls and women was horrific. Was Felicitas taken by Gilberto as part of the "spoils of war," as were so many women? Did she go willingly, following him from Chihuahua to Durango where they married in December of 1914? We probably will never know but we do know well that the atmosphere for women was one of fear, constant threats, and trauma. She was four months pregnant at the time of their marriage in Tlahualilo. Famous photo of Mexican Revolution federal soldier with his wife and child. No documentary evidence tells us what happened with Gilberto after the birth of their son. Was he killed? Historians estimate that 1 million Mexicans died during the Revolution so it is a possibility. The flu epidemic of 1918 killed another 300,000 Mexicans. Did the terrible illness take him? Is that why Felicitas came to the United States the following year? Perhaps Gilberto escaped to the US-side of the border, took another name, started another family and lived out his life here. We simply don’t know.

We know that Felicitas reported to the census enumerator that she crossed the border in 1919. We know that she met John Lucas that year and married him in 1920. In 1924, Felicitas was living in Juárez and acquired a local border crossing card. She had dropped Leyva and took on her mother’s maiden name, Fierro. By1930, both Felicitas and John were married to different people. John was married to Lola B. Lucas and still living in El Paso. The Census recorded that John’s household included his son, John Jr. Felicitas was married to Saturnino Chasco and living in Juárez with her husband and her son, Pascual. There is a twist to the story, however. A 1921 Texas birth certificate shows that John Jr. was the son of Felicitas (whose color was listed as “Spanish”)and John Sr. (whose color was listed as “Negro”). As Felicitas returned to Mexico, relocating to Ciudad Juárez with her older son Pascual sometime before 1924, John Jr., or Johnny as he was called, stayed in El Paso with his father and eventually his step mother, Lola. Finding the birth certificate punched me in my gut. Without the presence of this birth certificate, it would be easy to assume that Lola was his biological mother. They are listed in the federal census together and in John Sr.’s obituary. My first thought was that Felicitas was not allowed to keep her son. My second thought was that Felicitas did not want to return to Mexico with a Black son. Either scenario is heart-breaking. Did John Jr. know he had a brother on the other side of the border, Pascual? Did he see his birth mother? Did she want to see him? How could a mother leave her child? These are the same questions I had asked about myself and my birth mother and my sister through much of my life and that’s how interrupted stories work. The fragmented stories that haunt us, the ones we can’t let go of even if we have only fragmentary knowledge, may be the very ones that speak directly to our lives. Just as I came to understand and forgive my biological mother Guadalupe for leaving me, I believe that Felicitas also needs understanding and compassion. Bridging the interrupted stories in our families allows us to acknowledge, forgive, and love the generations before in order to heal ourselves and the generations to come. Bridging the ruptured stories allows us to understand our connections among each other, both in tragedy and hope. Finding John Lucas and Felicitas Leyva permitted me to see how two very different individuals, divided by nationality and race, came together amidst their deeply traumatic experiences, seeking a better life and having hope for the future.

2 Comments

Zonia Vasquez Grace

8/29/2018 02:37:55 pm

My parents were immigrants from Rio Bravo and the ejido of Reynosa Diaz. My mother was forced to cross the Rio Grand to Penitas, Tx. sometime in her childhood.

Reply

Alberto

12/31/2020 09:58:34 am

Wow just wow. What a great tale of perseverance and strength.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022