|

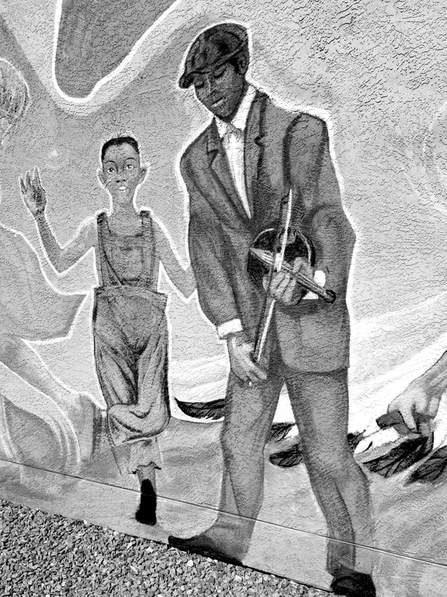

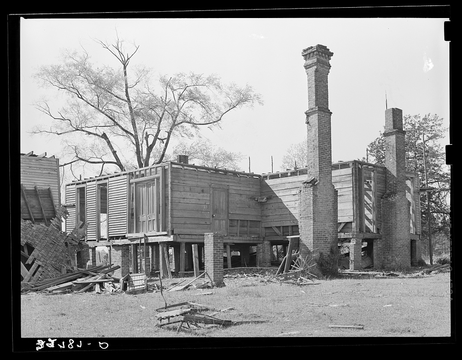

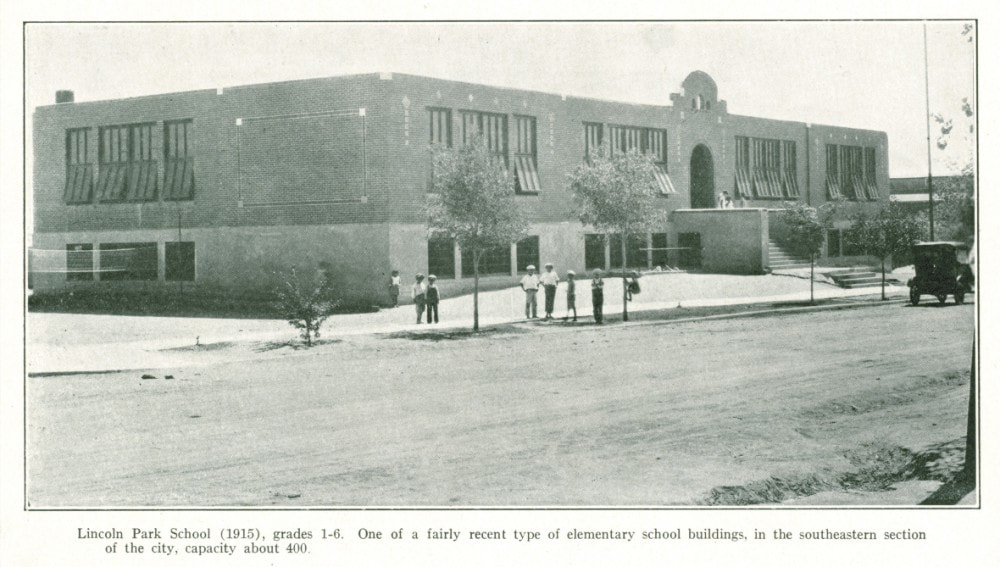

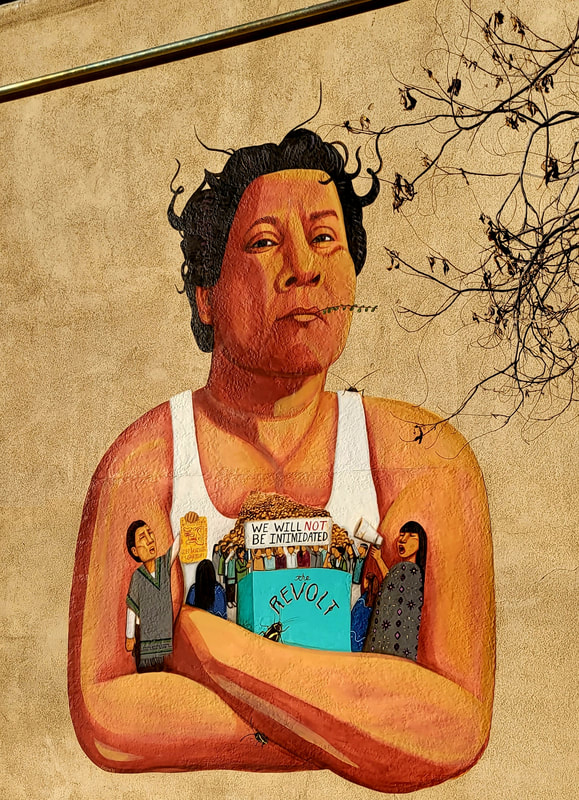

B & W photo of mural at Chamizal National Memorial commemorating the multiracial community of El Paso. There are stories that live on in our families as fragments, as small details shared casually in the midst of conversation. We must never underestimate their power, however, or undervalue their place in our familial healing. Bringing these interrupted stories to light and creating the bridge that connects the past to the present is part of the recovery of our whole selves. The consequences of the stories embed themselves in our physical make up-- our skin color, our hair texture, or our gait. They survive in us spiritually, mentally, emotionally, and physically. Creating the bridge over the rupture allows us to understand ourselves and our ancestors, to acknowledge them and to heal. Exploring the life and times of John Lucas, my great aunt's husband, is one of the ruptured stories that wove itself throughout my childhood. Looking back on my growing up, especially now as a scholar of borderlands history, I am not surprised at the ways in which race and skin color played themselves out within the confines of my small, nuclear family. While the two, race and skin color, are not synonymous, they are linked. Like so many other Mexicano families, we were of varying shades. My father, of Rarámuri descent, was so dark that during his time in West Virginia during World War II, he was perceived as “colored” and was not served in restaurants. My mama, on the other hand, was so white-skinned that White people didn’t think she was Mexican. As a consequence, she witnessed countless denigrating conversations against our people while she was in public. Believing her to be another white woman, white women felt free to degrade Mexicans in front of her. This is a classic Mexican American story. So, too, are the stories of families who are relieved when their children are born with whiter skin. “Que bonita. ¡Tan blanquita!” How many of us were told to stay out of the sun lest we get too prietas? The insidious colorism within our people is without question. The colonial-era casta paintings, with their endless combinations of racial intermixture and the subsequent range of skin colors, have nothing on us! When my mama and daddy argued, they hurled racialized code words against each other like vinagrón, a black scorpion-looking arachnid that used to be common in our desert community. My father would respond to being called a vinagrón by calling her un niño de la tierra, a white cricket-looking insect with a powerful bite. Sometimes, in the heat of a fight, my mama would add, “Tu tía se casó con un hombre negro!” as if it were the height of insult. And to her, who cherished white skin, it was. Despite her attempts to anger him, this mention of his aunt often de-escalated the fight as my daddy sighed and stopped to tell me about his tía Felicitas. I remember his voice would soften as he recounted the difficult lives that the women in his family faced due to being impoverished, Mexican women. De mulato y mestiza, produce mulato, es torna atrás (ca 1715). Painting by Juan Rodriguez Juárez. During the colonial period, every conceivable intermixture of people was categorized although in day-to-day life, only a select few categories were actually used. The fragments that my father shared with me of his aunt's story were few. Felicitas had come to El Paso during the Mexican Revolution, found work as a maid in a brothel, met John Lucas and married him. That’s all I knew yet I remained intrigued with tía Felicitas my whole life. Could I find Felicitas, a poor campesina born somewhere in Northern Mexico during the Porfiriato who migrated across the border during the chaos of the Mexican Revolution? Could I find her husband John Lucas when I knew almost nothing about him? For years, I searched archives and historical documents for clues about Felicitas and John. Finally, one day four years ago, I found mention of them in a tiny announcement in the January 29, 1920 issue of the El Paso Herald. There, next to an ad for the “calyx skirt” and just below an article pitting the intelligence of brunettes against that of blondes, was an article, “El Pasoans wed in Las Cruces.” The couple married in Las Cruces, no doubt, to escape Texas’ anti-miscegenation law. Despite our treatment as second-class citizens, Mexican Americans were legally defined as white. In the early 20th century, Las Cruces, New Mexico provided opportunities to Black El Pasoans that were denied by Texas law, including the right to marry a “white” woman and get an education at the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts. In the early twentieth century, as Felicitas and John wed, Black men and Mexican women created intimate relationships while facing criticism and threats from the judicial system. The classification of Mexican and Mexican American women as “white” made Mexican-Black marriages illegal in many states, including Texas. In her 2017 book Porous Borders: Multiracial Migrations and the Law in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands, historian Julian Lim (PhD, JD) writes about the precarious situation of interracial marriages between Black men and Mexican women in early El Paso. Although El Paso was certainly a more accepting city than other Texas cities, white supremacy still took root and flourished. Lim writes about a group of Black men and Mexican women who were arrested as “miscegenationists” in 1893. Lim cites an El Paso newspaper’s warning following their arrests: they were “only the inauguration of a general movement against all violators of the laws against miscegenation, adultery, and fornication.” It didn’t matter that some of the couples were married in places where they could marry (Mexico, for example). Their marriage was still against Texas law. As one observer wrote, the men were in trouble for marrying their color, but not their race. The day following the arrests, numerous Black families moved across the border to Ciudad Juárez. (See chapter 2 in Porous Borders for more on this story.) A Texas law passed just five years before Felicitas and John married made intermarriage a criminal offense punishable by two to five years in the penitentiary. A 1925 Miscegenation law declared interracial marriage a felony and nullified interracial marriages even if they occurred in a place where these marriages were legal. Despite their efforts, Felicitas and John found themselves breaking the law through their marital relationship. Texas' anti-miscegenation law remained on the books until 1967. The complexity of Black-Mexican relations continued into the 1930s and beyond. When El Paso's city registrar, announced in 1936 that city documents would designate Mexican Americans as "colored" in birth and death records, it created a strong defensive reaction from both Mexican Americans in El Paso and Mexicans in Juárez. A letter to the editor from J. Hamilton Price that fall stated that Mexican Americans had no reason to be outraged. He described the many marriages between Black men and Mexican women, going so far as to say that "negro-burros" was the common name for their offspring. (See Beyond Black and White.) It was within this contradiction between the existence of inter-racial marriages and intimate relationships contrasted with the deep anti-Black sentiments of many Mexican Americans that my great aunt Felicitas and John decided to marry. Despite facing possible criminal charges for their relationship, the 1920 Federal Census showed them living in El Paso in an area with a majority ethnic Mexican population in addition to several Black families. Felicitas and “Juan,” as he was called in the census were the only inter-racial couple. Felicitas’ son, five-year-old Pascual Molina, lived with them. As I poured over census records, city directories, and newspapers, the life and times of John Lucas drew me in. El Paso's Black population has always been small-- 2 to 3%. The early history of the city's Black community was intertwined with that of the Mexican immigrant community. The city's first Catholic Church for Spanish-speaking parishioners, Sagrado Corazon, and the first African American church, the Second Baptist Church, are within blocks of each other in El Segundo Barrio. What brought African Americans to this predominantly Mexican West Texas town? Lim argues that El Paso represented a gateway to new freedoms for the Black, Mexican, and Chinese people who migrated there. For African Americans, it was a way to escape the oppressiveness of Jim Crow and the increasingly virulent white supremacy of the South. As I learned more about John, it made more and more sense. Migrating to the border from East Texas, it seemed that John was indeed escaping the violence of Jim Crow. Ruins of an old plantation in Marshall, Texas by documentary photographer Russell Lee, 1939. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. John Lucas' roots in the East Texas town of Marshall went back to his grandparent's generation in the decade before the Civil War. Historian Jacqueline Jones writes that in the period before the Civil War, Texas was a “perennial magnet for southern planters seeking to take advantage of cheap fertile land suitable for cotton cultivation the eastern and central part of the state…” (Goddess of Anarchy p.7) Indeed, during the Civil War thousands of slaves made what Jones calls the “brutal wartime ‘middle passage’ from Virginia to Central Texas.” (xiii) John Lucas’ grandparents, Lucion and Ann, born respectively in Virginia and Mississippi in the 1830s, made that forced relocation to Texas sometime by 1855 when their first daughter Nancy was born. Their son, Willis, was born in Marshall in 1856, four years before the Civil War broke out. During Willis’ early childhood, Marshall was radically anti-union and pro-slavery. Victoria White, John's mother, was also born in Marshall in the 1850s. I have little doubt that Willis’ grandparents and parents were enslaved. There would be no other reason for Black people to come to Marshall in the 1850s. By 1860, when John's grandparents were children, Harrison county where Marshall is located, had more enslaved people than any other county in Texas, making it the richest county in Texas and the fifth largest city. White workers complained that the presence of so many skilled enslaved people was creating competition and taking their jobs away. During the Civil War, Marshall became an important Confederate city. Following the end of the Civil War, during Reconstruction, the situation of Marshall’s Black population eased some and it was during this period that 19-year-old Willis married 15-year-old Victoria White. The couple had seven children, including John. John Lucas was born in June 1883, the same year as well-known civil rights leader Dr. Lawrence Nixon who challenged Texas’ white only Democratic primary. By the time Lucas and Nixon were born, Marshall was long “redeemed” from Republican control and the former powerful antebellum families were in power again. White supremacy flourished in Marshall during John’s childhood and young adulthood. In 1903, when John was twenty-years old, the Los Angeles Herald reported that a race war had broken out in Marshall. Following the arrest of “a negro,” the newspaper reported that a group of Black men helped him escape, ambushing the Constable and killing him. By 6 p.m. that evening, 600 White men were armed and ready for revenge. They took a Black prisoner from the jail, Wallace Davis, and lynched him. The report warned that every Black had to leave Marshall or face a “war of extermination.” In the years before John came to El Paso, there were at least ten other lynchings in Marshall, all men, all Black. They faced torturous treatment at the hands of White mobs, including unspeakable acts of mutilation. In April 1909 alone, four Black men were lynched over the course of two days. When Lawrence Nixon witnessed a lynching in front of his medical office in Marshall, he decided to leave, eventually coming to El Paso a few years earlier than John. The racial antagonism and violence had to be unbearable for Marshall's Black community. As a young man, John had options-- he could leave East Texas and seek a better life. John and Lola eventually lived across the street from this school. Their home was demolished and is now part of Lincoln Park. It is unclear where John lived between 1910 and the first evidence of his residence in El Paso in 1917. He doesn’t appear in Marshall in the 1910 Census although there is a John Lucas married to Palace Lucas nearby in 1910, both listed as mulatto. It could be them or not. By 1915, John’s brother Charles was living in El Paso, working as a porter, and living on Palm Street on the same block where we found Felicitas and John living five years later. Perhaps Charles came earlier and called for his brother to join him as racial violence in their home town escalated. John was listed as a boilermaker helper in 1917, an occupation he would hold for decades. As a skilled craftsman, John was part of the legacy of the enslaved men of Marshall who worked in skilled occupations such as mechanics. John retired with a railroad pension under the last name “Lacy,” a name he father had also used, for reasons unknown. Just a few years after arriving in El Paso, John met Felicitas. In 1919, Felicitas Leyva crossed the border into El Paso with her four-year-old son, met John, and they married in 1920. When I looked at the 1920 Census, reading between the lines, it seems that the Census enumerator spoke with Felicitas. She did not know English and the notation of John as “Juan” gives us a clue. While the birthplace of other US-born residents listed on the Census form lists their state, John’s birthplace is listed as “United States.” It seems unlikely that he would not say Texas. I wonder how much they knew about each other? Did John speak Spanish? How did they make a life together, having crossed so many borders, geopolitical and social? Sometime between 1920 and 1930, Felicitas disappeared from John's life. There is no documentation of divorce because by then their marriage had been declared null by Texas law. In the 1930 Census, 45-year-old John appears married to 38-year-old Lola Lucas with an 8-year-old son, John, Jr. They, like Felicitas and John, lived surrounded by Mexican neighbors. John and Lola remained married until John’s death in 1959. John was buried in Concordia Cemetery in February 1959, survived by Lola, John Jr, and three grandchildren. Almost a century after the controversial marriage of my great aunt Felicitas and John, my Afro-Mexican grandchildren remind me that these histories matter. Little by little, I am building bridges across the chasms in my family history, connecting the past with the present and starting to heal. In addition to Julian Lim, Porous Borders, and Jacqueline Jones, Goddess of Anarchy, see: "Good Neighbors and White Mexicans: Constructing Race and Nation on the Mexico-U.S. Border" Author(s): Mark Overmyer-Velázquez Source: Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Fall 2013), pp. 5-34 and Beyond Black and white: Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in the U.S. South and Southwest.Stephanie Cole and Alison M. Parker, editors. Texas A & M Press, 2003.

3 Comments

Corinne Chacon

3/14/2018 08:17:15 am

Thank you for sharing your family's journey. Fascinating. How interwoven it is with the social, economic and cultural realities of race, gender and class. Case study to the max and that's only one pair of people! Gracias.

Reply

RUTH LUCAS

5/1/2018 01:36:16 am

I AM JOHN LUCAS LEYVA DAUGHTER

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

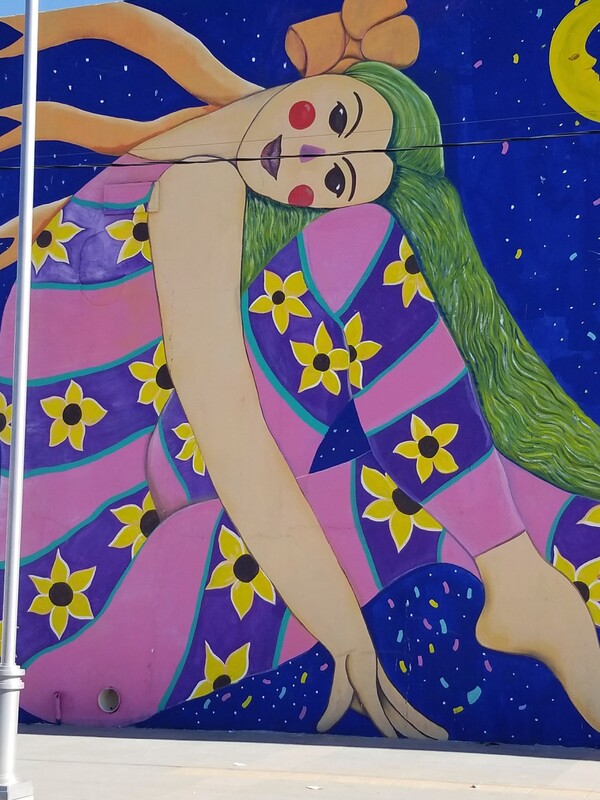

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022