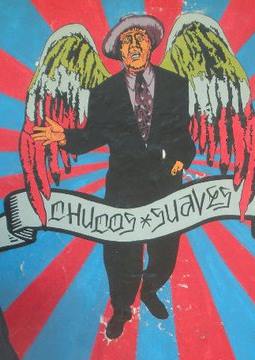

Photo courtesy of Ana Reza. Beauty is a bridge between the past and the future. Recently, I wrote a blog post about Barrio Duranguito, a south side El Paso neighborhood that has been under siege for a year and a half after the City Council voted to demolish it for an arena. We could say it's been under siege for decades, a victim of purposeful disinvestment by its property owners and neglect by the City. The interrupted story of the barrio has been utilized to create an image of the neighborhood as one that is ugly, worthless, and old and its people disposable. The true story of Duranguito has been interrupted by the actions of the City government, the property owners, and sometimes the media. Since voting to demolish Duranguito in October 2016, the City has allowed it to fall into further decay: a drive by demolition in September 2017 caused damage to many buildings. A vacant lot has been allowed to become a dumping place. Homes are boarded up. Gardens, fenced in by the City, are dying. It reminds me of a scene in the 1981 movie Zoot Suit. As the defendants were nearing their trial, they were not allowed to bathe or shave or change clothes. They appeared before the jury looking disheveled and unclean, just what the 1940s White jury imagined Mexican Americans to be: dirty Mexicans. The powerful create the negative image that society expects and then justifies injustice by pointing to the dirty Mexicans or the unsightly barrio as not worth saving. That is part of the interrupted story: we are kept from the true images of Mexican American youth who take meticulous care of their appearance or the beloved barrio where residents paint their apartments, plant geraniums and fruit trees, and sweep the sidewalks in the early mornings. A historic building on the corner of W. Overland and Chihuahua Street following the demolition attempt. Photo courtesy of Paso del Sur. In this scenario, what can we do? The residents and allies of Barrio Duranguito don't have the millions that its enemies have. We don't have access to the political power that its opponents have. But we do have something important: we have our bodies to put to work and we have hope. Those are powerful. In recent weeks, we have been bridging the interrupted story by creating beauty. The vacant lot is slowly being transformed into a garden. Windows are painted beautiful colors. A drab chain link fence is transformed by red plastic cups. Duck tape spells out the words "Viva Duranguito!" Trees are wrapped in colorful yarn and children paint the sidewalks with chalk. A walkway by the once beautiful rooming house, The Mansion, is cleaned of its clutter. We are people from different backgrounds, in ages from elementary school to 90, who are from El Paso and who traveled here from other cities. We are all called together by our vision of what Duranguito truly is: a place of beauty. Creating beauty is our form of resistance against forced uglification and destruction. Photos courtesy of Ana Reza. In her 2013 book Urban Alchemy: Restoring Joy in America's Sorted Out Cities, psychiatrist Dr. Mindy Fullilove outlines the steps to restoring joy in distressed neighborhoods and cities by describing nine elements. Element 3 is "make a mark." She writes, "As urbanists, we make signs to start a new dialogue between people and their spaces. Whether we are noting history or current events, beauty of horror, we are indicating that the space is important. Signs are the beginning of the change we need to make." By creating spots of beauty and art in a barrio under siege, we are making a mark, declaring joyfully "This place is important." In her chapter on "Element 3: Make a Mark," Fullilove writes that "art calls us." We have seen this happen before in barrios under attack. In 2010, we opened Museo Urbano at 500 S. Oregon, in El Segundo Barrio. Working with muralist David Flores, we commissioned a mural to commemorate pachuco culture, whose roots were in that very neighborhood. As he worked on "Chucos Suaves," residents and students found inspiration. Soon, they asked if they, too, could paint murals and with permission of the property owner, they began their work of beautification and resistance. Soon, the tenement courtyard was filled with smaller murals painted by barrio residents, mostly young men, that called people in. I remember once, while sweeping the courtyard on an early Sunday morning, a woman in her 80s who was walking home on her way back from church, asked if she could enter. A striking mural of the United Farmworkers Union eagle had caught her eye. She shared with me the story of a strike she had participated in in the 1950s and pulled out a tattered UFW union membership card that she still carried with her. Art calls us and beauty encourages hope and imagination.  Monet Munoz and Sandra Enriquez on Museo Urbano opening day, standing in front of the UFW eagle mural painted by a resident. Left to right: Detail from "Chucos Suaves" by muralist David Flores; UTEP MEChA students painting their own mural; Visitors from the Boys and Girls Club taking notes on the community-painted murals they are viewing. The interrupted story has the power to hurt us, as individuals, families, neighborhoods, cities, and even nations. To bridge the story is equally powerful. Bit by bit, we are bridging the story of Duranguito by making a mark and affirming that this place and these people are important.

1 Comment

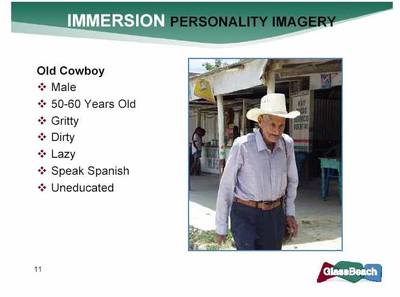

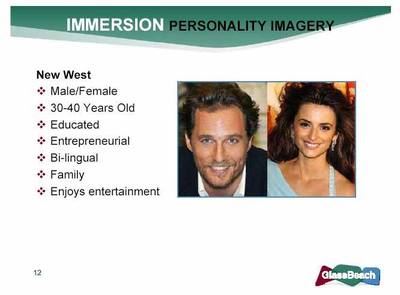

Antonia Morales Fall 2016 UPDATED April 27, 2018 On September 12, 2017, I stood in the early morning coolness with 89-year-old Antonia “Toñita” Morales as we watched a bobcat tearing into the buildings surrounding her home in Duranguito, a barrio on El Paso’s south side. We tried to yell above the horrifyingly violent noise of the machine for the workers to stop; the demolition crew member stared blankly at us as he maneuvered the bobcat back and forth. As it tore into the brick walls, the dust flew around him and bricks thumped to the ground. Workers standing around him mocked us as we yelled that we had an injunction against demolition. It was a surreal moment as I walked around Chihuahua Street surveying the damage, especially the ragged craters left by the bobcat in the corner of each historic home. Unlike other demolitions, the crew had not destroyed any one building entirely. Instead, they had damaged most of the residences and businesses on Chihuahua Street: the old Martinez Grocery, the homes just recently occupied by the Francos who sat outside each evening visiting with neighbors, Don Lupe who tended his beloved garden every year, Olga, and others. As I walked along the street, I thought of the many residents who had been pushed out in the months leading up to that morning, most under duress after months of threats and harassment. One said he was happy to leave but he was a newcomer to that barrio with no particular ties to the place. Fellow Paso del Sur (PDS) member Dr. David Romo and I had walked that barrio many times over the previous year. We had stood on porches and sat in living rooms listening to the histories, the fears, and the dreams of the people who had lived in Duranguito sometimes for decades. Duranguito is more than its architecture. It is the stories of people who made their lives there. Duranguito residents meeting, Fall 2016. How did we get to that horrible October morning event? Eleven months before the demolition attempt, in October 2016, the El Paso City Council voted to demolish El Paso’s first neighborhood in order to build a sports arena that even their own employee testified in court would be utilized perhaps a total of two months of the year. The vote to displace the long-time residents in October 2016 was followed by a reversal in December 2016 to not demolish the neighborhood then followed by a renewed commitment to destroy the tight-knit neighborhood in January 2017. The year and a half of fighting to save their community had taken a toll of people’s health: high blood pressure, depression, and other stress-related illnesses spiked. It has also created a stronger resistance to displacement. Toñita often said that she would fight for her community to the end. Barrios are complex, living beings. They can grow and thrive and they can experience disease. They develop over time as relationships are created and strengthened, both the relationship of the neighborhood to the city and the relationships among the people. When parts of them are destroyed, whether it be the demolition of a building or the dislocation of a resident, it is as we had lost a limb. With the displacement of each resident, the life essence of the barrio begins to decline. The decision to destroy the barrio was much more than simply “economic” and “political,” it was what the municipal government hoped was the final blow in a decades-long campaign of disinvestment, ignoring the code violations of negligent (and wealthy) landlords, and efforts to disappear the history of the place. The City and the developers hoped that by interrupting the true story of Duranguito's rich history and the contributions of generations of its residents, no one would oppose the demolition and displacement. In previous posts, I’ve discussed the ways in which stories are interrupted within individual lives and within families—trauma, shame, forced forgetting, and even not caring. For neighborhoods like Duranguito, the interrupted story is just as insidious because the history has been purposely kept from the people of the neighborhood and the residents of the city. As importantly, the living histories of the barrio, the people themselves, have been characterized and treated as disposable people, without history and without value. The residents of Barrio Duranguito are a vulnerable group. The neighborhood’s average income is $10,000/ year and many survive on monthly Social Security checks of $800. The great majority are renters (who have few rights in Texas) and Spanish is the primary language. The rent averages $350 a month. They are almost all Mexican and Mexican American. Women outnumber men with many older women living alone. The average age is 65. Most have lived in the area for decades. When PDS met with the residents in October 2016, we offered our help. Unanimously, they told us they wanted our help to save their homes. Next, they wanted their landlords to bring the buildings up to code. Although the events of October 2016 were shocking, their roots lay in a revitalization plan adopted by the City ten years earlier in October 2006. Around 1999, a group called the Paso del Norte Group, with a secretive membership made up of the elites of El Paso and our sister city, Ciudad Juárez, formed in order to create an economic plan for both cities. On both sides of the border, low income communities were targeted for displacement in order to bring what developers called “progress” and “revitalization.” In reality, the "revitalization" would enrich their members. Low-income people and almost all El Pasoans were left out of the discussion of how "progress" would be envisioned for our community. Glass Beach Study 2006. On the left: El Paso now. On the right: What El Paso could be. The battle against displacement through the Paso del Norte Group plan has brought an important question to the forefront: who is disposable? In 2006, the City of El Paso paid $100,000 for a branding study conducted by the Glass Beach Firm, which didn’t exist before or after this particular contract, contrasting what El Paso is now and what it could be. There were several images that stood out as we reviewed the study, in particular the one referring to people. The words used to describe El Paso’s current population included “gritty,” “dirty,” “lazy” -- words that had been used against Mexican-origin people since the 1820s when Anglo Americans first came to Texas. It also included the descriptors “Spanish-speaking” and “uneducated.” The last two could describe many of the residents of the south side, including Duranguito—Spanish is the primary language in these barrios and many residents have not had the opportunity to acquire formal education. These two images made it clear who was disposable in our community. Much of the narrative, both in the case of El Segundo Barrio and Duranguito, revolves around history. In attacks against the south side both in 2006 and 2016, the City and their representatives said there was nothing historical in either El Segundo Barrio or Duranguito. Notably, of nine historic districts in El Paso, only one is South of the freeway, south of the railroad tracks. In 2016, the City attorney argued that Duranguito could be demolished because there were no historically designated buildings there. Of course, it was the City’s decision to go against their own 1998 archaeological study that recommended historical designation for Duranguito so it was circular logic. The City decided not to validate Duranguito’s history as significant and then turned around and said they could demolish it because no one had designated it historical. Yet, we know that the neighborhood, which dates back to the 1850s, a neighborhood built on top of an 1827 Mexican land grant, which in turn was built upon the ancestral land of the Manso people, and whose buildings have been deemed architecturally significant by experts, is replete with history. It was not just the architecture that was historic. (And no question that the beautiful architecture is significant.) The living history, the people of the barrio, was important. In 2006, PDS began utilizing the concept of living history to describe the residents of El Paso’s south side barrios. Our history is embodied in the buildings, yes. But our living histories are embodied in the people themselves, the fronterizos whose lives and experiences have created our city. Their lives embody the history of migration, economic development, of Mexican and Mexican American culture, of women’s work, and life en la frontera. As Toñita often says, she doesn’t have to read history; she has lived it. Last fall, our Mayor invited a self-proclaimed historian to talk about the significance of Duranguito. He is known for speaking against south side barrios and dismissing their historical significance in support of City-backed demolition plans. The mayor allowed him to speak for over 11 minutes in a vitriolic rant against Duranguito. (The last time I spoke before the Mayor and City Council about Duranguito, I was allowed one minute.) He reassured the Mayor and Council that Duranguito was not worth saving, that the historians of Paso del Sur had everything wrong and that we were, in fact, chupacabra historians. Chupacabras, you might know, are mythical creatures who suck the blood out of livestock. The mayor laughed with glee at that city council meeting as he proclaimed “Historian throw down!” On May 1, the El Paso City Council plans to appoint him to the Historic Landmark Commission. While it was a ridiculous scene, there was an underlying acknowledgement that history is powerful. The women of Duranguito visiting with each other before their displacement. How do we bridge the interrupted story of a neighborhood? For Paso del Sur, we started with the people. We listened as they spoke and shared their stories of raising families, of migrating to the United States, of working for decades to contribute to the economic growth of our city. We listened deeply to understand how they saw themselves as historical actors. We listened deeply to what they loved about their space. Listen to an example here. And we researched the deep history of the place. Dr. David Romo has conducted meticulous research on Duranguito and generously shared it on our Facebook page. You can find it here. Two particularly beautifully researched and written examples are here ("The Forgotten Lessons of the Ponce de León Settlement Acequias") and here ("Doña Benancia: The Woman Behind the Gold-Digging Men"). Interrupting the historical story can create disease and demoralize people. Bridging the story can plant the seeds of dignity and healing. Photos courtesy of Paso del Sur (Facebook page: PasodelSurEP)

|

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022