|

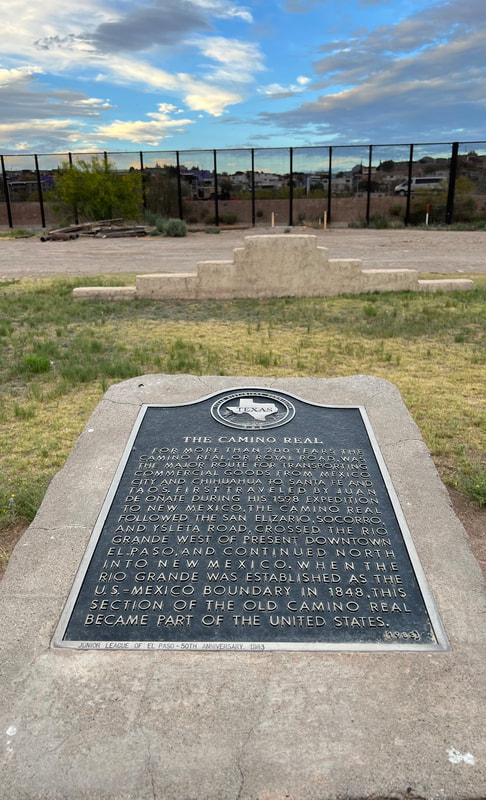

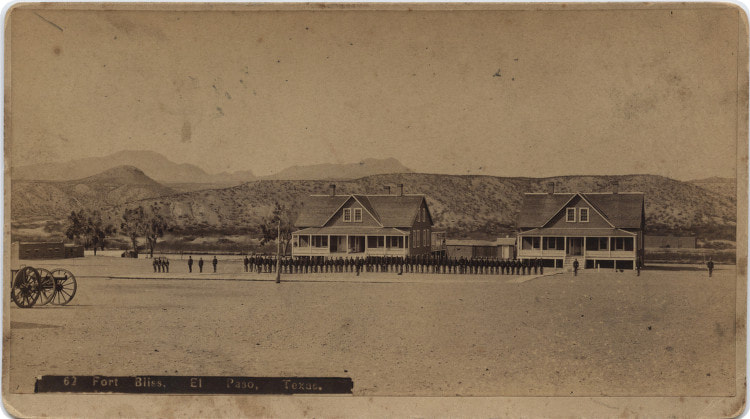

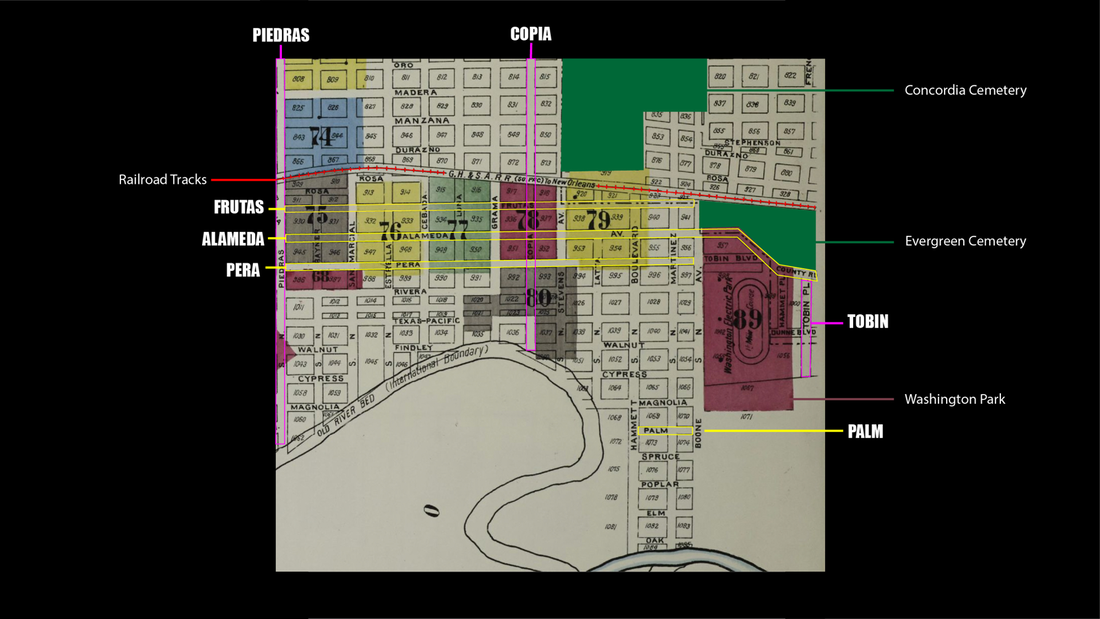

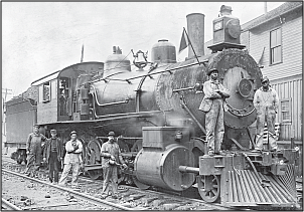

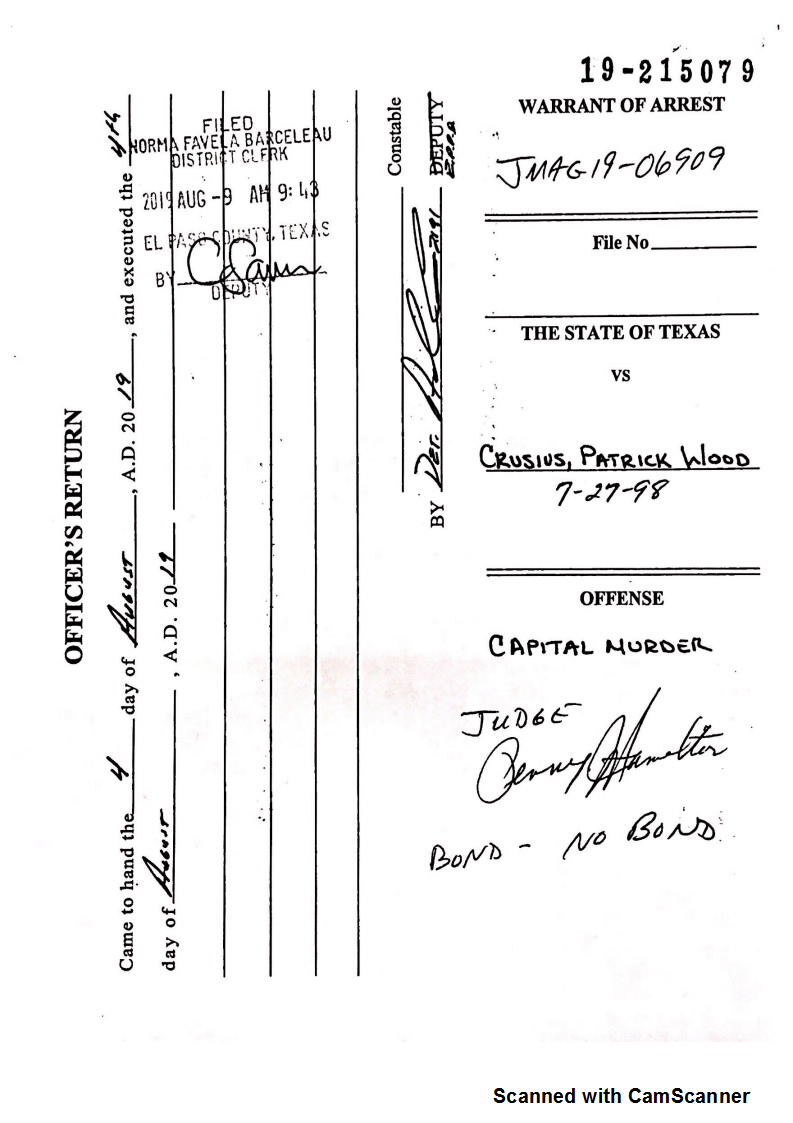

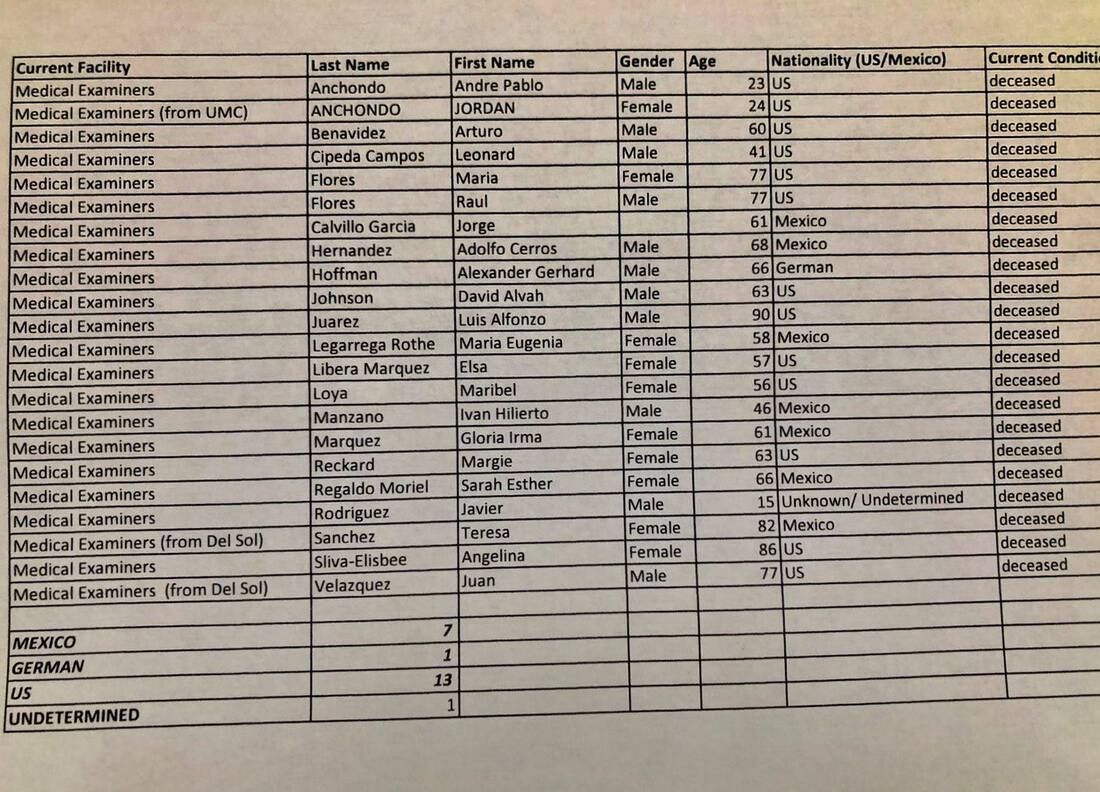

“History is the fruit of power, but power itself is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous. The ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.” ― Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History I sit in a parking lot on the western edge of my university campus overlooking a very busy Interstate 10. Beyond, I can see the border fence. A military vehicle makes its dusty way along the service road in between the fence and the canal with its recent addition of concertina wire. Along this part of the border fence, it is common to see multiple law enforcement agencies—the Border Patrol, the National Guard, State troopers. I am determined to observe all I can. The vibrant multicolored homes in the distance on the Mexican side of the border catch my eye. Homes painted bright blue, green, purple, and yellow stand out against the desert browns. They are part of a project called El Paso-Ciudad Juarez Mágico, sponsored by the El Paso-based non-profit Amor por Juárez. Behind the non-profit, created in 2009 during the heightened drug violence in Juárez, was the now-defunct Paso del Norte Group (PDNG), a powerful group of binational developers and business leaders formed in the 1990s to remake the Paso del Norte region into a more profitable region for the already wealthy members of the group. While the PDNG used Amor por Juárez to talk about making poor neighborhoods more beautiful in order to create a better quality of life for their residents, on the El Paso side, it targeted poor immigrant neighborhoods like the Segundo Barrio and Barrio Duranguito. The border is filled with such contradictions. It is filled with power made invisible. Sitting in my car with the air conditioning running in the mid-afternoon heat, I search the horizon for the tract of land that holds a centuries-long history of power made invisible by half-told and sometimes untold stories. It is the site of the first permanent Fort Bliss, Hart’s Mill, and a collection of historical markers. Located on West Paisano in El Paso, along the border, Border Patrol vehicles sit parked on the other side of the fence. As I think about this narrow piece of land and the history that infuses the buildings and the historical markers, I reflect on the ways in which they make power invisible. In 1598, Juan de Oñate passed through the area on his way to Nuevo Mexico. His mission was to conquer and settle New Mexico. He is a controversial figure. His cruelty to Indigenous people is documented yet often contested. Did he order the feet of men from Acoma Pueblo cut off or was it simply their toes? That is what historians debate sometimes. In 1614, he was exiled from New Mexico for excessive cruelty to both Native people and fellow colonists. Yet, in El Paso and in this strip of land along the river, he is simply “Don Juan de Oñate, Adelantado and Capitan-General, Governor of New Mexico.” When the Oñate expedition reached the river here in 1598, the Rio Bravo/ Rio Grande was truly a wild river, impossible to cross in most places without the intimate knowledge of the land and the river that the Tampachoa people held. The Tampachoa, called the Mansos (docile) by the Spanish, and their ancestors have lived along the river for centuries. They are still here. In the desert, water always draws people. It was the Tampachoa who taught Oñate and his expedition where to ford the river. Although the actual crossing occurred to the east in what is now Socorro, a historical marker here celebrates the crossing and the naming of El Paso del Norte. The State of Texas erected the marker in 1936 as part of the state-wide commemoration of the centennial of Texas independence. As I write about here, El Paso’s love of conquistadores and Spanish explorers is rooted this era. Since El Paso was not part of Texas in 1836, we had no traditional Texas history to memorialize. So instead, El Paso turned to conquistadores as a stand-in for white Texan history. The El Paso del Norte historical marker is accompanied by others. The Camino Real marker, for example, states that Oñate was the first to travel it in 1598. We know that the many royal roads used during the Spanish colonial period were ancient and well-used trade routes developed by Indigenous people. Indigenous history is invisible here along the border fence.  Jesusita Siqueiros Hart/ Special Collections, UTEP Library Jesusita Siqueiros Hart/ Special Collections, UTEP Library Here, next to the thirty-foot tall border fence, we learn about the waves of conquistadores, U.S. military leaders, and U.S. businessmen who came to El Paso del Norte (now El Paso and Ciudad Juárez) beginning in the late 16th century. Simeon Hart, whose historical marker touts him as “the main source for securing military supplies” for the Confederacy also notes his ability “to render great service to the Confederacy”; the marker highlights the flour mill that he “founded.” There is no mention of him as a slave owner. The 1860 slave census shows five enslaved people living at El Molina (the mill), ranging from two months to 45 years of age. The slave schedule notes their ages and their sex, but they remain nameless. They may be the “servants” shown in the 1860 federal census—Charles, Sally, Patsey, Rhoda, and baby Charles. Nor is there mention of his wife Jesusita Siqueiros, the daughter of a wealthy Chihuahua family who owned mills. Beginning in the 1820s, white U.S. men came to northern Mexico where they intermarried into wealthy, politically connected Mexican families, giving them access to political, social, and economic contacts. I will always remember a column by a well-known local writer who simply stated in 2002 that Hart “married a Mexican girl from southern Chihuahua.” Women become invisible in these narratives. In the 1870s, Hart sold part of his land to Fort Bliss and the officers' quarters remain today. Most recently apartments, the buildings are now boarded up and slowly decaying. This was the one of many locations of what was originally called “the Post Opposite Paso del Norte.” Founded in 1849, just a year after the end of the U.S.-Mexico War, its purpose was to stop Indigenous people, especially the Apache and Commanche, from crossing the new border. The historical marker mentions Hart and the building materials but says nothing about the purpose of the military fort directly on the river. Nearby is Doniphan Park once a playground for the children living in the now mostly empty neighborhood. The park is named after Colonel Alexander Doniphan who marched through the area with the 1st Regiment of Missouri Mounted Volunteers in 1846 as part of the U.S. invasion of Mexico, which resulted in Mexico losing over half its territory. Doniphan and his men won the Battle of Brazito near Las Cruces, New Mexico, and went on to Chihuahua City. From the Spanish colonial expeditions into Indigenous lands to the U.S.-Mexico War of 1846-48, and to the Confederacy, this is narrow, almost hidden strip of land, venerates conquest without ever using the word. It makes power invisible. It is up to us to make it visible.

0 Comments

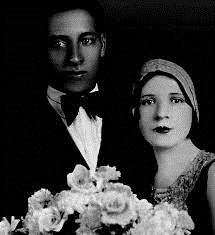

Last week my partner Diana Bynum and our grandson Joaquin Leyva joined the Journey for Justice, a caravan organized by Witness at the Border to bring attention to the distress of migrants coming to the United States and to call for justice. The caravan travelled the entire 2,000 miles of the border. Together with his grandmother Diana, Joaquin rode hundreds of miles, stopping at border crossings where local communities told them about the suffering of migrants and what they were doing to help ease it. For Diana, it was important to do something in this moment of crisis. To witness what was happening in other communities. Here in El Paso, Diana had volunteered many hours, feeding migrants, doing arts and crafts with children, making shoelaces, and more. In a poem reflecting on that experience, Joaquin wrote “On the caravan I Saw new things. Mountains made Of boulders. Deserts filled with Cacti. Walls built to isolate.” Diana and Joaquin returned from their journey to a crisis at this border, our home, El Paso. A few days ago, the Texas governor called in the National Guard who placed concertina wire along the border so that no one could cross. Each day, hundreds if not thousands of migrants wait on the international bridges on the Juárez side of the border. US immigration officials are releasing up to 1,000 migrants per day in El Paso and hundreds are on the streets as the temperature drops below freezing. Non-profits and churches are quickly organizing to provide shelter for the people on the streets. Shelters on both sides of the border are overwhelmed. Many migrants are from Venezuela. Venezuelans are now the second largest group of migrants encountered by the Border Patrol, surpassed only by Mexicans. In the past eight years, millions of venezolanos have left their homes in desperation. They go to neighboring Latin American countries. They come here. In their home country, over 75% live below poverty, defined globally by the World Bank as $1.90 per day. The daily minimum wage is less an $1.00. Inflation is unbelievable. In 2018, it hit 130,060%. It hovers around 500% now. A cup of coffee is beyond reach of most people at the U.S. equivalent of $2.50. While that may seem affordable to us, it is more than a day’s wages for many Venezuelans. The migrants wait. It’s ironic that the Spanish word meaning to wait and to hope is the same—esperar. The migrants here at the border do both. They wait, sitting on sidewalks surrounded by bags of meager belongings, covered in blankets, or in lines waiting to eat or be taken into the warmth of a temporary place to stay. And they hope. Hope that the long journey here will allow them to wait out the crisis in their country. Hope that they will be able to work and find security and stability. Hope that their children will thrive. Hope that someday they will be able to return home. The border is always a place of contradictions. To live on the border is to be constant witness to the inhumanity of government policies and the generosity and kindness of people. El Pasoans are volunteering at shelters, and providing water, coffee, blankets, and coats from cars parked in areas where migrants wait. They donate meals to shelters and give of their time. It is a generosity of spirit that we have always shown on the border, perhaps because we have little. Perhaps because so many of us remember our parents and grandparents who came seeking a better life. Joaquin ended the poem by writing, “No matter how Dim the light may be. There is still a Little bit of hope. And a little bit we can do to help. And if we can do Just that, we can Create bigger Change.” As I drive past the hundreds of migrants on the streets of El Paso, I hold on to that little bit of hope. For them. For us.  Jerry Leyva and Esther Chavez, 1929 Jerry Leyva and Esther Chavez, 1929 Presented at Corazón, Historia, Raíces/ El Paso, Texas November 5, 2022

|

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022