|

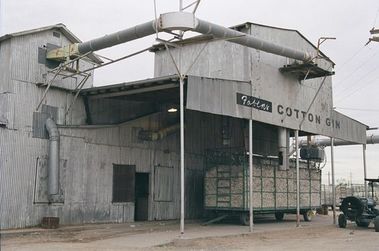

Article 15 1. Everyone has the right to a nationality. 2. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 Almost a decade ago, I served as an expert witness in the federal trial of a man named Domingo who was being tried for continuing to return to the United States after multiple deportations. He faced a long prison sentence. His lawyer told me that Domingo had always claimed to be born in the United States, near El Paso, yet there was no paper trail to support that. Would it be possible to be born in the US in 1955 yet have no birth record, no medical record, and no school record? I knew the answer was “yes” because on the border the poor, especially the poor, are invisible. And as I worked through the parts of his story, I knew his memories rang of truth because I could draw on similar stories from my own family. I will always remember the day I walked into court as the only witness in his defense. When I walked in, he tried to stand up to greet me. He looked at me with such expectant eyes. I remember that we tried to shake hands but the guard stopped us. I wanted to speak to him but wasn’t allowed. I wanted to tell him that I would do my best, as a historian, to tell the history of a place where if you were poor, if you were a child, if you looked “Mexican,” you could go unnoticed. Today, on Declaration of Human Rights Day, I especially think about Domingo. Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights cites “the right to a nationality” as a human right. Domingo was, and I am sure continues to be, a man without a nationality. Although Domingo has never waivered in saying that he is an American, the United States denies him. Mexico, where he has been “returned” time and time again, also denies him. Domingo knew that he was born and raised in the Lower Valley of El Paso, a largely agricultural area in the 1950s that was dedicated to cotton. He knew that his earliest memories were of a bar. When the lawyer mentioned its name, I recognized it as a long-time institution in the Lower Valley. He remembered his mother leaving him and his siblings there, sometimes for days, while she disappeared with different men. On those days, the children would beg door to door for food and the neighbors would fed them. Fabens Cotton Gin from fadingad.com Domingo knew that he had never gone to school. He remembered that around age 9, his mother took them to live with his grandmother in El Paso and that he and his sister had run away from the abusive household. They went to Yuma, Arizona where they lived in an abandoned house. One day his sister left home to find food and never returned. She was his last connection to his blood family. As an adult, he married and had children and he worked to support his family. And he was deported and returned. And was deported and returned. It became a horrific cycle of his trying to remain in his country with his family while being returned to Mexico, a country that he did not know. I worked hard for several weeks, piecing together a plausible scenario where a boy could be born and grow up in the mid-20th century United States with no documents to prove his existence. How could he be so invisible? As I researched the history of the area he remembered as his birth place, it started to make sense. In a rural area, it would be likely that Domingo was delivered by a midwife rather than a hospital. Or perhaps hid mother gave birth by herself. Along the border, midwives have often been the best option for poor women who couldn't afford hospitals. For many Mexican Americans born in the 1960s and earlier, this was true and it has been the source of problems. In 2008, the ACLU sued the U.S. Department of State, charging "that the State Department categorically questions the citizenship of virtually all midwife-delivered Mexican-Americans born in southern border states." You can read about it here. Subsequently, a settlement was reached so that US citizens could get passports, but it points to what the ACLU calls a "blanket race-based suspicion" of Mexican Americans' citizenship. As I continued to think about his memories of his mother and the bar, I considered that she could have worked in prostitution. In the mid-1950s, the Lower Valley was not only the site of a processing center that administered thousands of bracero contracts every month, but local farmers hired braceros to work in the fields, especially picking cotton. The year that Domingo was born, 398,650 Bracero contracts were signed with temporary agricultural workers from Mexico. Scholars have noted the rise in women working in prostitution during the Bracero Program. In oral histories, former braceros also mention the prevalence of prostitution. Was Domingo’s mother a sex worker? Perhaps. He didn’t remember his father so a single mother with multiple children would very well turn to sex work for survival. It is a historical reality. Without a birth certificate or medical records he could easily have slipped through the cracks of the educational system as well. For much of the twentieth-century, officials looked the other way when children in agricultural areas missed school. When the compulsory attendance law was passed in Texas in the early twentieth-century, Mexican-origin children were often excluded from its enforcement. All the components of Domingo's story has some basis in historical plausibility. Each part of his story reflected parts of my own family's history. In the weeks leading to the trial, I worked in the archives, searching through County records and reading books. I pieced together the snippets of his memory and contextualized them in the larger history of the region and the border. I prepared to testify. The day of the trial, the judge asked me to present my testimony to him prior to the jury hearing it. In the end, he decided very little of my testimony would be admitted; it was "not scientific" he said. I was allowed to say very little. I was deflated. After so much work, I could not tell the story that made sense to me as a fronteriza and a historian. During the cross examination, the prosecutor grilled me. He undermined my validity as a witness. He eventually asked me, "Isn't it true that the US does not deport its own citizens?" "Actually the US has deported its own citizens" and I started to discuss the deportation campaign of the 1930s. He quickly thanked me. When both sides finished their argument, the jury went into deliberations. Domingo's lawyers had already warned me that juries typically ruled in favor of the federal government. As I prepared to return home, the jury remained in deliberations. I returned home deflated and depressed that I had not been allowed to give my expert opinion in support of Domingo's story. Two days later the attorney called: Domingo had won. The jury was shocked to hear that the US had deported US citizens. Perhaps Domingo was telling the truth. The jury ruled that the US had not proven that Domingo was not a citizen. It was a bittersweet victory, however. Since he could not prove that he was a citizen, he could continue to be deported. Mexico would continue not to accept him since he was not born there and he would continue to return to the United States, his home, always under the threat of future deportations. But he would not go to prison. I think of Domingo frequently. I wonder where he is and how he is. I think about how his story has played out in so many families along the border, including mine. I think of him, a man without a nationality, who never gave up on the country he knew was his. Today marks the beginning of a year-long campaign commemorating the upcoming 70th anniversary of the signing of the foundational Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As I remember Domingo, I know that an expansive concept like universal human rights is enacted in the most personal of ways in our individual lives and that like Domingo, who never gave up, we must never give up on fighting for human rights.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022