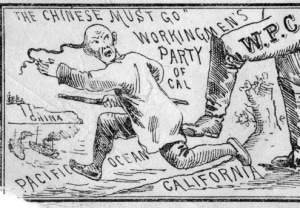

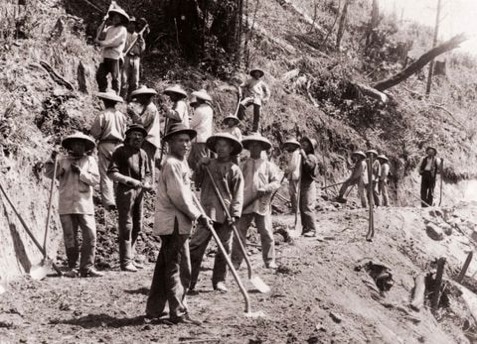

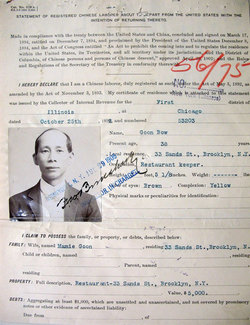

Reflecting on Exclusion/ Working towards Inclusion: The anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act5/6/2017 One hundred and thirty five years ago the Chinese Exclusion Act went into effect. The 1882 act excluded Chinese immigrants from entering the United States and in 1902 was extended to all immigrants from Asia. It was the first immigration law that excluded people based on nationality. Chinese workers had been recruited to work on the nation's railroads and they came with the hope of sending their wages home. They did the hardest labor building the expanding railway system and other workers claimed that they accepted such low wages that it brought down everyone's wages. The anti-Chinese movement began in California and soon spread nationally. Today, a number of organizations in San Francisco are remembering this anniversary with a call for inclusion. The AFT 2121, Chinese Progressive Association, Chinese for Affirmative Action and others declare "On the 135th anniversary of the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, we stand together in solidarity to resist the Muslim travel ban and the anti-immigrant and refugee policies. Excluding immigrants on the basis of race and religion was wrong then and it's wrong now!"  Chinese immigrants who were here before the passage of the Act, which was extended in 1894, could apply to remain in the United States. Here restaurant owners Goon Bow, living in Brooklyn with his wife Mamie Goon, apply to leave the United States with the intention of returning. The Chinese Exclusion Act had a direct impact on the U.S.-Mexico border and today there is a thriving Chinese Mexican community along the border from Texas to California, from Chihuahua to Sonora. For Chinese workers who were already in the United States, they could remain if they could prove they were here before the passage of the law. The roots of the Chinese community in El Paso grew lie in the completion of the Southern pacific Railroad in 1881. Many Chinese workers, initially hired to work in construction gangs for railroads, remained in El Paso following the completion of the railroad from the Pacific to El Paso. Over 1,200 Chinese men worked bringing the railroad to El Paso and census reports show that the Chinese community numbered around 1,000 in the 1880s. Chinese men turned to laundries and restaurants after their railroad work was completed and El Paso had many. Although the Chinese population diminished, numbering under 300 by the 1910s, cultural and social institutions grew, including the Chinese Benevolent Association and a number of tongs, organizations comprised of people from the same town or district in China. Coming from the same village or region in China provided a sense of community and identity for Chinese immigrants so far from home. It is estimated that up to thirty percent of the men from one village could be working overseas at any given time El Paso's oldest cemetery has a Chinese cemetery within it, the history of El Paso's Chinese community reflected in the tombstones. Although there had been Chinese migration to Mexico since the 17th century, the greatest numbers came in the decades following the US Exclusion Act. Chinese men married Mexican women and soon there were Mexican Chinese families in the Mexican north and in Mexico City. The men integrated themselves into the Mexican economy. Some Chinese immigrants were smuggled into the United States; others crossed as Mexican citizens. Many remained on the Mexican side even though anti-Chinese violence grew during the Mexican Revolution of 1910 and threatened Chinese Mexican communities in the 1920s and 1930s. During the period of intense anti-Chinese sentiment, Mexican women who had married Chinese men lost their citizenship and were sometimes deported to China with their husbands and children. Despite violence on both sides of the border, the Chinese American and Chinese Mexican communities survived and thrived. Today, the Chinese American and Chinese Mexican community in El Paso is fighting to preserve what may be the last standing Chinese laundry in the city. The City Council and the building's owner, Billy Abraham, plan to demolish it as part of an effort to put an arena to benefit the wealthiest developers in town. The possible demolition has made news across the state, including in Houston's Chinese language newspaper.

It gives me great hope to see communities organize to remember a dark episode in US history and to demand inclusion rather than exclusion. And it gives me great hope for border communities to fight against the erasure of their history.

1 Comment

Pam

5/6/2017 07:33:19 pm

Yolanda, thanks for sharing this. The Chinese Exclusion Acts were one in a long series of disgraceful actions by our government. We have to stand in solidarity to fight exclusion and racism!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022