|

I write this in the period in between el Dia de las Madres in Mexico and Mother's Day in the United States. On the border, we celebrate both. I was born 61 years ago in this in-between period and for most of my adult life, I have spent these days thinking about my two mothers: Guadalupe who gave birth to me and Esther who gave me life. Perhaps "remembering" is not the right word: questioning my life, agonizing over my birth, and feeling sad and angry are better descriptions. For many decades this time beginning with el Dia de las Madres and Mother's Day brought me great pain.

I remember as a young woman vowing that I would not be like either of my mothers. I would never abandon my child and I would never do anything to make my child feel unloved. I would be a mother that mothered in opposition to the way I had felt mothered. By the time I was a young girl, the mother who raised me was bitter and defensive. As I came of age, her anger became more apparent; her fear engulfed her. I didn't understand why and I felt unloved. She often blamed me for her fear. As a teenager, I experienced her telling me many times that she had not wanted to adopt me. She cautioned me not to smile too much because God would punish me if I seemed too happy. The family assured me that it was simply "su caracter," the way she was. When she was in her 80s and I took her to her doctor because she believed people were trying to kill her, he told me the same thing. "That's just how your mother is." My relationship with my birth mother was equally frought with pain. When she sent a message through her sister that she wanted to meet me when I was 14, having not seen me since I was a newborn, I didn't have to think twice. No. No, I do not want to meet her. I was hard and judgmental. No real mother would give up her child, I told myself. When she was murdered seven years later, I was stunned but still angry. I don't write this to paint them in a negative light. Rather, I write this to reflect on my own limited compassion. My own limited understanding of their suffering. My own self-centered perspective. Every May for much of my life, I was sad and angry. Then everything changed. I forgave and I was forgiven. I loved them and suddenly, I understood their love. It was a miracle. It was the healing I ached for but didn't know how to achieve. I longed for my mother Esther's love. I didn't understand until the last years of her life that she equally longed to be free enough to show me that love. Her life-long suffering had been intense. Born in the midst of the Mexican Revolution, what she remembered as a tranquil and comfortable life in Chihuahua was disrupted when her family moved to El Paso for safety. Orphaned at age 14, she was left to help her two older sisters raise her younger brothers and sisters. She remembered caring for her baby brother Salvadorsito who was just a few months old when his mother died at age forty. She dropped out of school in sixth grade. She felt responsible for him. She fed him and bathed him. She cared for him day and night and he became "her baby." Then he died a few months after his mother. She remembered finding him lifeless and she always blamed herself for his death. She went on to suffer nine miscarriages and that initial loss of "her baby" replayed itself through decades of her life. When her older sister was repatriated along with her family during the Great Depression, she was devastated and abandoned. In Mexico, her baby sister died. Loss after loss defined her life. When I was born to her young niece when she was 44, the walls she had built around her to protect herself were tall and almost impenetrable. Yet, she took me in and the first photo that my new parents ever took of me when I was several months old shows her holding me, looking at me with love. I'm smiling up at her face. I know that in the early months after they brought me home, she sat with me day and night, afraid that if she left me alone, I might die. Two pounds when I was born and two months premature, the doctor said I probably would die. What courage she had to take me in knowing I could be yet another baby that she could lose. I didn't understand that for much of my life. When she said she didn't want to adopt me, I believed she was telling me that she didn't love me. What she really meant was she was profoundly afraid. And still she took me in. In the months before she died, she often told me that she loved me and that she didn't know what would have become of her if she had not adopted me. I had never heard the words "I love you" from her growing up. The first time she told me, my heart melted. She died in my arms at age 88. It was after her death that my relationship with my birth mother was healed also. My birth mother Guadalupe was born into a physically, emotionally, and sexually abusive home with a violent father who often told her he didn't believe she was really his daughter. When I met her sister twenty years ago, she confirmed the stories of violence and abuse that I had heard from family members. Lupe was 18 years old when she became pregnant with my sister and me. It is only recently that I found out who my father was-- a 19 year-old airman from Kentucky. I doubt he ever knew he was going to be a father. He went on to marry a Kentucky girl and had several children. From what I know, his life was good, filled with family and community, work and church. Lupe was left behind to figure out what to do, pregnant and poor. After my birth, she moved to Tijuana, living a chaotic life until she died at age forty. In letters she wrote to her sister, she always asked for me. Now, I can't imagine her suffering, knowing where I was and rejected by her only living child. I was always angry that she gave me away. Intellectually I knew that she had no way to support me. I knew she did what was best for me. Yet, I hated her. When her sister gave me a framed photo of her, I stuck it in a drawer and forgot about it. Then it all changed. I was invited to the home of a well-known writer who had built a beautiful chapel to the Virgen de Guadalupe with a spectacular stained glass window. In the afternoon sun, the light shone through the window and illuminated the brown, adobe walls of the chapel. I had brought some roses to leave for the Virgen, who I had been devoted to since I was a child. I was staring up into the face of la Guadalupana when I heard a voice. "Forgive me. I love you. Forgive me. I love you." I knew immediately it was my mother connecting with me. My heart jumped, my breath stopped, my eyes filled with tears. It was all I needed to hear from her. All I needed to know. An hour later I spent half an hour vomiting bile and with that burning, yellow liquid went the anger and the hate. I came home, took her long-forgotten photo out of the drawer and placed it on my childhood piano. After so many decades of anger and guilt and sadness, I had learned to forgive my two mothers and I had been forgiven. I understood how they loved me despite their own suffering and in turn, I learned how to show love to my son. Anger and hate are powerful but so are forgiveness and love. It took me decades to understand this and to accept the love that Guadalupe and Esther offered me in the only ways they could. "I love you" and "Forgive me" became the healing that allowed me to finally learn to truly love and truly forgive. Today, the in-between time between el Dia de las Madres and Mother's Day is filled with gratitude for the two mothers who each gave me life.

0 Comments

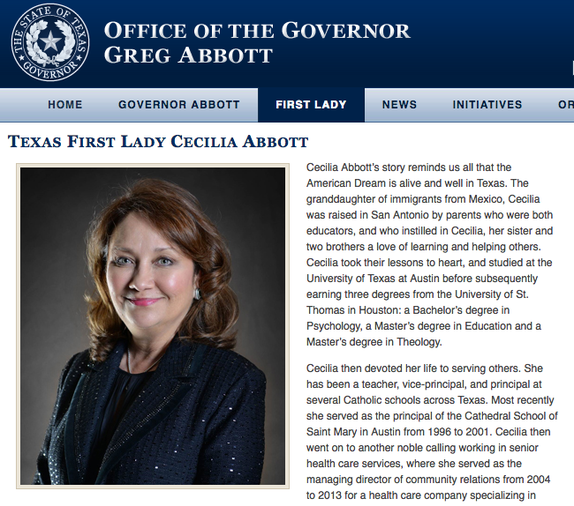

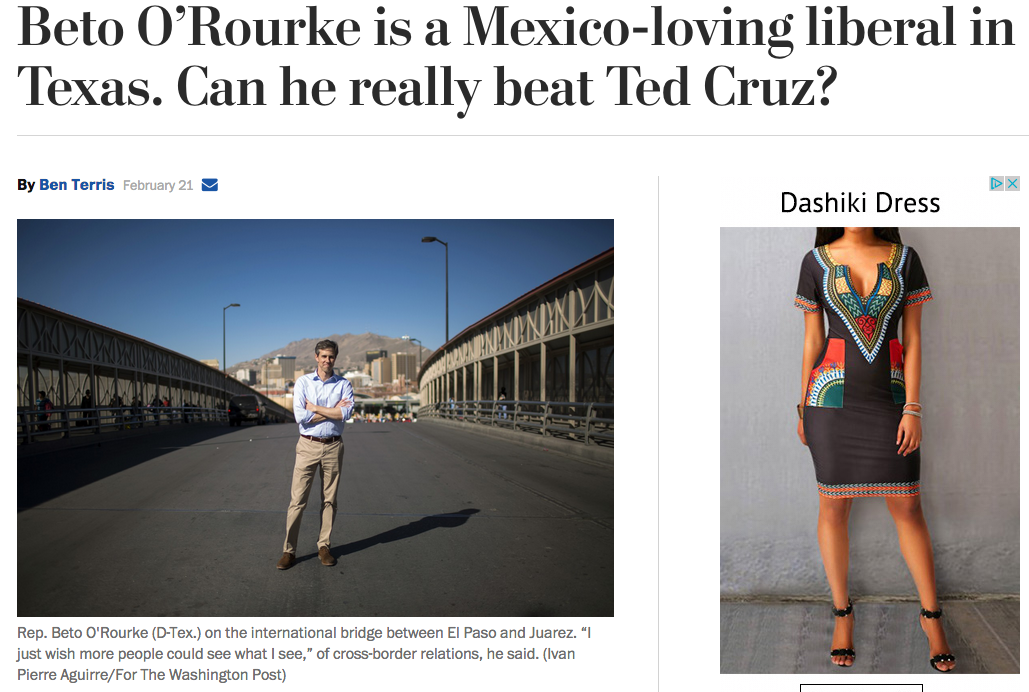

To the US border politicians who love Mexicans (but hate us at the same time): You love us. You love us not. You love us. You love us not. Governor Greg Abbot, why did you sign the anti-sanctuary city law this Sunday in a surprise Facebook Live event? Senate Bill 4 not only bans sanctuary cities and campuses, but now local law enforcement can be charged with a misdemeanor for not honoring requests from immigration agents to hold immigrants who are subject to deportation. Those who violate the law are subject to civil penalties as well. Police officers are allowed to ask a person's immigration status. Immigration advocates say it is an "ask for your papers" law. We know it will endanger the relationship between police and immigrant communities, and that doesn't help anyone. Thomas Saenz, president of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) says the law is dangerous, will lead to racial profiling, and will alienate half the state's population. MALDEF plans to challenge the law in court. Texas has filed a pre-emptive lawsuit to get the legislation declared constitutional before the many challenges to it begin. Why, Greg Abbott, why? I thought you loved us the way you love your Mexican American mother-in-law Maria de la Luz Segura, the daughter of immigrants, who you featured in your campaign. You say you got 40% of the Latino vote in Texas because of the one video showing the both of you together. Recently, AG Sessions visited border cities, characterizing the border as a war zone. El Paso is "ground zero", according to the former US Senator from Alabama. City, County, and State officials quickly came to the defense of our border community, citing its low crime rate. We reacted to his military imagery because we know that in this atmosphere, we are considered “the enemy.” But Greg Abbott, you beat him to it. Back in 2013, your campaign page on immigration proclaimed "The Front Line Of Illegal Immigration." But I thought you loved us. How often have you bragged that your wife is the “first Hispanic First Lady” of Texas? Your Texas gubernatorial website describes Cecilia Abbott this way: “Cecilia Abbott’s story reminds us all that the American Dream is alive and well in Texas. The granddaughter of immigrants from Mexico, Cecilia was raised in San Antonio by parents who were both educators, and who instilled in Cecilia, her sister and two brothers a love of learning and helping others.” It then goes on to boast, “With her husband’s election as Governor, Cecilia made history by becoming the first Hispanic First Lady of Texas.”  The border- both cities and states-- allow for a particular kind of politician and civic leader: one who appeals to what used to be called a century ago "the Mexican vote" while still acting in ways that hurt and even devastate Mexican American communities. These politicians protect themselves as well as appeal to ethnic Mexicans through their close association with Mexican women. For example, a century ago Mayor Tom Lea was a member of the KKK. He wore silk underwear because he believed it would keep typhus infected lice from infecting him, according to David Dorado Romo's Ringside Seat to a Revolution. One of contemporary admirers continues to tell me that he couldn't have been a member of the Klan (or been anti-Mexican) because his second wife was Mexican! Even Wikipedia enters the debate when someone going by the name “Galleryowner” disputes the characterization of Lea by two historians, Shawn Lay and David Romo. Galleryowner writes, “Shawn Lay states that Mayor Tom Lea was a member of the Ku Klux Klan without evidence. Letters to Mr. Lay for proof have gone unanswered. Mr. Romo repeats Lay's allegation, taking it further to mis-characterize Mayor Lea as having a fear of being contaminated by Mexicans. Mayor Lea's second wife, Rosita, was Mexican. Neither book is a reliable source for information on Mayor Tom Lea. - Gallery owner.” So, of course, Lea couldn’t be anti-Mexican—he had Rosita! We have our own “love us/ love us not” millionaire in El Paso right now, too. A leader in the de-Mexicanization of our city, he is married to a Mexican woman, also a millionaire. People say, how can he be anti-Mexican? He's married to a Mexican! And then there is US Congressman Robert O'Rourke. He may not be married to a Mexican woman, but as a child he was cared for by a Mexican woman who gave him the nickname "Beto," by which he still goes. (So the story goes.) Many are led to believe that he is part Mexican because of his use of a Mexican nickname. Recently, the Washington Post called him a “Mexico- loving liberal.” Media reports show him in Ciudad Juarez, casually walking around the streets, recommending bars, looking at home in the Mexican border city. Few reports remind us that he introduced the Paso del Norte Group plan when he was a city representative. The plan, created in part by his millionaire bi-national developer father-in-law Bill Sanders, would demolish one of the most historic and densely populated Mexican immigrant barrios in the nation. It also called for the demolition of Duranguito, a fight we are engaged in today so that this older, mostly immigrant neighborhood won’t be destroyed. Robert O’Rourke, I thought you loved Mexico. Oh, maybe you love Mexico, but not Mexicans.  Greg Abbott, signing SB4 tells us a lot more about whether you love us or not than your photo op with your mother-in-law. She may love you as a son-in-law, but we sure don’t love you as governor.

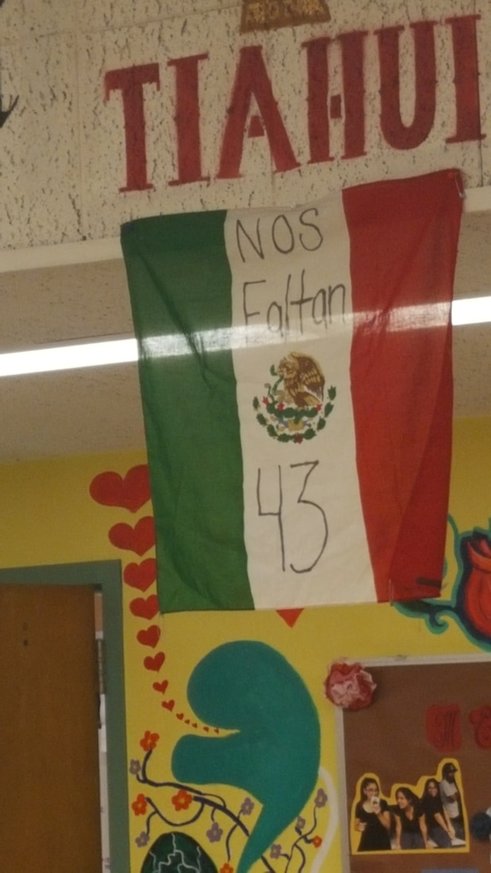

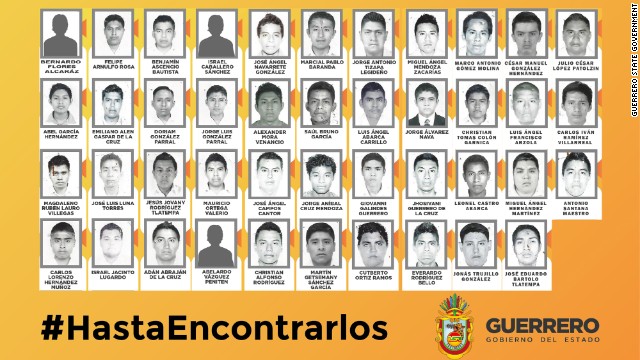

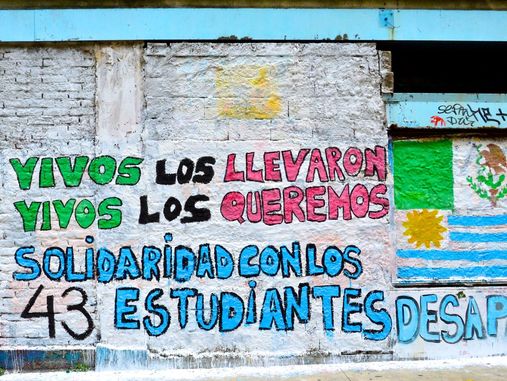

In a Trumpian-era of "alternative facts" what does the truth mean? And what does the truth mean when we are complicit in obscuring it? A few days ago, I heard the testimony of Mexican journalist Anabel Hernandez whose recent investigative book, La Verdadera Noche de Iguala, describes her findings around the disappearance of 43 normal school students on the 26th of September 2014. Speaking to an audience at the University of Texas at El Paso, Hernandez described how the students at la Escuela Normal Rural "Raul Isidro Burgos" in Ayotzinapa were disappeared in Iguala in the southern Mexican state of Guerrero. They are among 26,000 people who have been disappeared in the country, including women, men, children, and babies. Hernandez believes in naming names and she says she has the names of every person on the list of 26,000 disappeared. Over 100,000 people have been killed in the past decade as part of Mexico's war on drugs. Anabel Hernandez has uncovered evidence that the attack on the students that left the streets like "a river of blood" and their subsequent disappearance was the result of a collaboration among several levels of law enforcement with the military. The attack was an effort to disappear witnesses to the military removing two million dollars worth of heroin that had been hidden on the buses that the students occupied. The students had no knowledge of the heroin. They had "sequestered" the buses in order to get to a commemoration in Mexico City of the 1968 Massacre of Tlatelolco. The 43 first year students whose faces stare at us from the poster above have been missing for over two and a half years. Their parents continue to insist that the search for them must continue. On April 25, the parents arrived at the office of the Ministry of the Interior to request a meeting, continuing to demand that their sons be returned alive. After a hour of waiting for their request to be "processed," they began symbolically touching the wall that surrounds the Ministry building. They were met with tear gas grenades that injured five of the parents. Ayotzinapa students who were returning to Guerrero to inform the school of the attack on the parents were attacked by state police. So what does all of this have to do with the truth and with us?

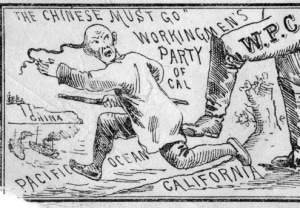

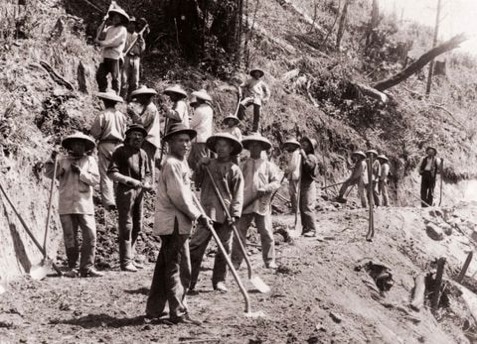

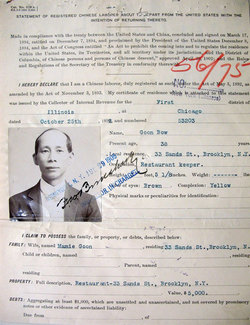

It has everything to do with us. Shocking images of the tragedies created by the opioid epidemic in the United States are increasingly reported in the media. The Center for Disease Control reports that 91 Americans die each day from opioid overdose. Increasingly heroin substitutes for prescription opioids. As a result of the increasing demand for heroin in the United States, Mexican drug cartels are turning to heroin as the profitable drug of choice. Heroin abuse has grown most dramatically in the Midwest and the Northeast. Whites between 18 and 45 years of age now have the highest death rate from heroin overdose. Increasing addiction to heroin is a complicated issue and the racial/ socio-economic politics behind how our government is treating this epidemic are another story. But we have to start by confronting the truth that the deaths and disappearances in Mexico are not solely a consequence of Mexican governmental corruption nor cartel criminals. The truth is that our government is complicit. The truth is that we are complicit as a society that consumes the drugs. The blood of the 43 Ayotzinapa students is surely on our hands as much as that of the Mexican government. Anabel Hernandez says that no nation can move forward without knowing the truth that they have a right to know. We not only have the right to know the truth, we have an obligation to take responsibility for the truth. This is even clearer during these times of "alternative facts" and a President who lies, exaggerates, and misrepresents. Only when we look truth in the fact can we begin to understand how our actions reverberate well beyond the borders of our nation. Reflecting on Exclusion/ Working towards Inclusion: The anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act5/6/2017 One hundred and thirty five years ago the Chinese Exclusion Act went into effect. The 1882 act excluded Chinese immigrants from entering the United States and in 1902 was extended to all immigrants from Asia. It was the first immigration law that excluded people based on nationality. Chinese workers had been recruited to work on the nation's railroads and they came with the hope of sending their wages home. They did the hardest labor building the expanding railway system and other workers claimed that they accepted such low wages that it brought down everyone's wages. The anti-Chinese movement began in California and soon spread nationally. Today, a number of organizations in San Francisco are remembering this anniversary with a call for inclusion. The AFT 2121, Chinese Progressive Association, Chinese for Affirmative Action and others declare "On the 135th anniversary of the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, we stand together in solidarity to resist the Muslim travel ban and the anti-immigrant and refugee policies. Excluding immigrants on the basis of race and religion was wrong then and it's wrong now!"  Chinese immigrants who were here before the passage of the Act, which was extended in 1894, could apply to remain in the United States. Here restaurant owners Goon Bow, living in Brooklyn with his wife Mamie Goon, apply to leave the United States with the intention of returning. The Chinese Exclusion Act had a direct impact on the U.S.-Mexico border and today there is a thriving Chinese Mexican community along the border from Texas to California, from Chihuahua to Sonora. For Chinese workers who were already in the United States, they could remain if they could prove they were here before the passage of the law. The roots of the Chinese community in El Paso grew lie in the completion of the Southern pacific Railroad in 1881. Many Chinese workers, initially hired to work in construction gangs for railroads, remained in El Paso following the completion of the railroad from the Pacific to El Paso. Over 1,200 Chinese men worked bringing the railroad to El Paso and census reports show that the Chinese community numbered around 1,000 in the 1880s. Chinese men turned to laundries and restaurants after their railroad work was completed and El Paso had many. Although the Chinese population diminished, numbering under 300 by the 1910s, cultural and social institutions grew, including the Chinese Benevolent Association and a number of tongs, organizations comprised of people from the same town or district in China. Coming from the same village or region in China provided a sense of community and identity for Chinese immigrants so far from home. It is estimated that up to thirty percent of the men from one village could be working overseas at any given time El Paso's oldest cemetery has a Chinese cemetery within it, the history of El Paso's Chinese community reflected in the tombstones. Although there had been Chinese migration to Mexico since the 17th century, the greatest numbers came in the decades following the US Exclusion Act. Chinese men married Mexican women and soon there were Mexican Chinese families in the Mexican north and in Mexico City. The men integrated themselves into the Mexican economy. Some Chinese immigrants were smuggled into the United States; others crossed as Mexican citizens. Many remained on the Mexican side even though anti-Chinese violence grew during the Mexican Revolution of 1910 and threatened Chinese Mexican communities in the 1920s and 1930s. During the period of intense anti-Chinese sentiment, Mexican women who had married Chinese men lost their citizenship and were sometimes deported to China with their husbands and children. Despite violence on both sides of the border, the Chinese American and Chinese Mexican communities survived and thrived. Today, the Chinese American and Chinese Mexican community in El Paso is fighting to preserve what may be the last standing Chinese laundry in the city. The City Council and the building's owner, Billy Abraham, plan to demolish it as part of an effort to put an arena to benefit the wealthiest developers in town. The possible demolition has made news across the state, including in Houston's Chinese language newspaper.

It gives me great hope to see communities organize to remember a dark episode in US history and to demand inclusion rather than exclusion. And it gives me great hope for border communities to fight against the erasure of their history. 1977 Austin, Texas 2017 El Paso, Texas In 1977, I participated in a historic farm workers march. I was 21 years old and an undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, part of a group that supported the work of the Texas Farm Workers Union (TFWU). I was working with numerous other social justice groups around Chicano rights, the rights of poor Mexican American neighborhoods, and lesbian rights. In February of that year the TFWU marched from San Juan to the capital in Austin. Later that year, they marched from Austin to Washington, D.C. I participated, carrying a TFWU flag that I had silkscreened. (Although honestly, I was no good at it... they called me La Tortuga because I was so slow at picking up the process.) This photo is the only one I have from my early days of working in community and organizing. Forty years later, I marched with the Border Farm Workers Center on May Day 2017, joining representatives from various groups including La Mujer Obrera, Paso del Sur, and of course, Sin Fronteras Organizing Project. We crossed the Santa Fe International Bridge and met organizers from Ciudad Juarez mid-way, near the bronze plaque marking the actual point where the U.S. and Mexican border is drawn in the middle of the Rio Grande/ Rio Bravo. People from both sides of the border shared words and songs. It was a day of reflection for me as I thought about the four decades between the two photos. What had I learned? I would love to hear what lessons you have learned. Please share them! I've tried to think about the five most important things I've learned and here they are. 1. The ways in which the powerful maintain power are more insidious than I could have imagined at 21. The municipal, county, state, and federal governmental entities support the wealthy in ways that are manipulative, corrupt, usually hidden, and involve a mind-boggling network including chambers of commerce, country clubs, the media and others. While I knew that intellectually and in general terms as a young woman, I know it now intimately having allied myself with working-class barrios for so many years. 2. The powerful know no borders. At the May Day gathering, a speaker from Juarez said, 'No hay fronteras para el capital." Capital does not know borders. International trade agreements, legislation, and the international networks of wealthy business people ensure that they and their money can move globally in an effort to continually seek more wealth. Stopping or controlling the flow of international workers is part of this. At this week's march, I heard "Los capitalistas no tienen pais. El pais de los trabajadores es la lucha." While we live in a time of making "America great again," it really has nothing to do with the United States. It is about making the wealthy wealthier, the powerful more powerful, and all at the expense of the poor, globally. 3. There are people who still believe in justice, who hold ideals of justice, of equality and who love humanity despite the backlash happening in the United States and Europe, despite the despair of working with few resources. 4. Despite people's intense suffering and even fear, they will not and cannot remain silent in the face of injustice. The poor and the marginalized communities will always find a way to express their rage and their dreams. 5. And the one I think is most important: In the face of great, overwhelming power, we may feel helpless and hopeless. I have certainly had days when I felt I couldn't do anything to make the world better. We may feel angry, bitter, judgmental and sarcastic. The question that brings me back to myself is "Why am I doing this?" If it is for any of these reasons listed above, I know I will not not be able to sustain fighting for justice. Only love can sustain radical action. Not mushy love. Not romantic love. Not nostalgic love. Rather, love that understands we are all connected, love that requires commitment, and love that acknowledges that even if we risk pain, we still have faith. I know that we have to maintain faith. We have to maintain hope. Without them, how can we believe in change? What lessons would you share? Please let us know. Mr. Silvestre Galvan has carried this banner of Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe in farm worker marches since 1965.

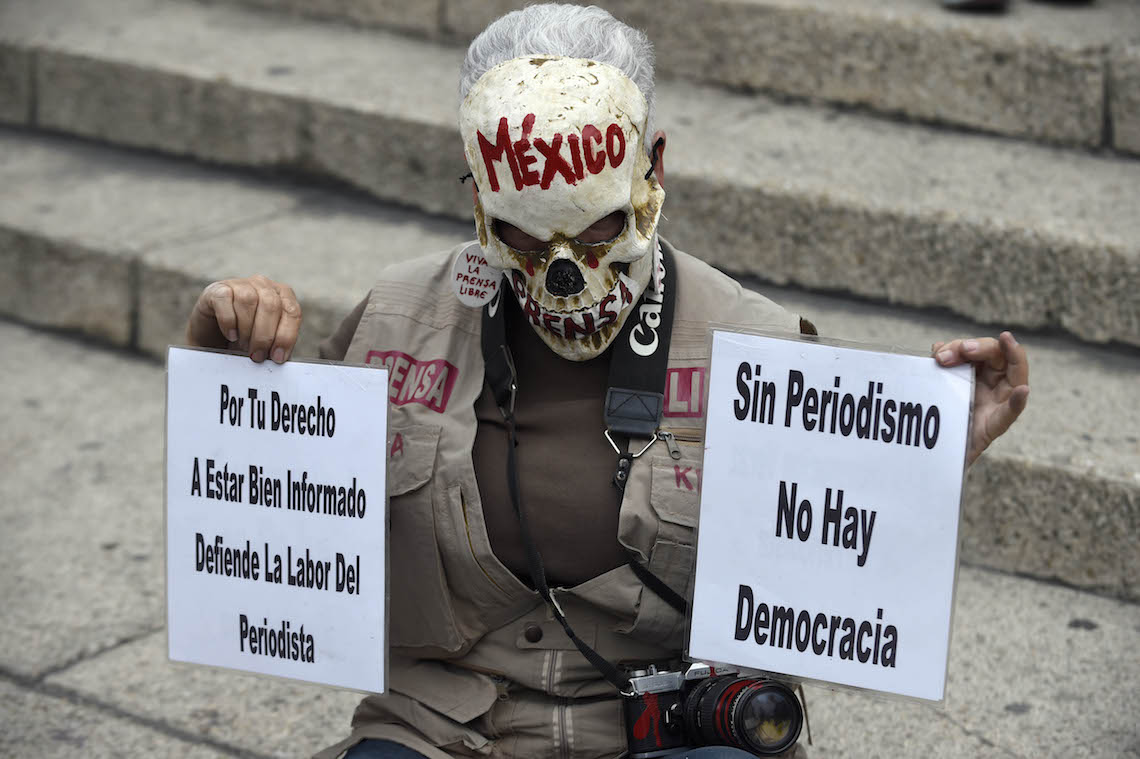

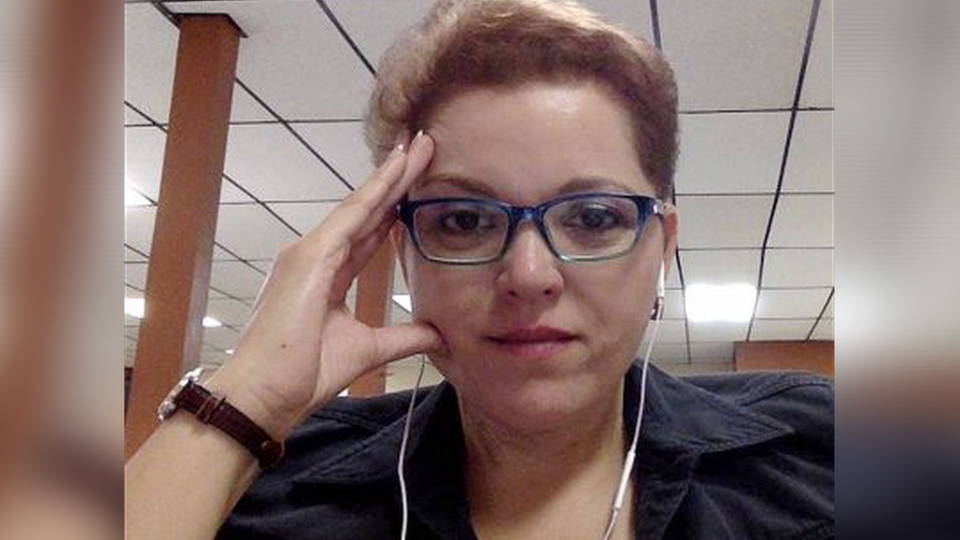

UPDATE on May 15, 2017: Today Javier Valdez Cárdenas, Mexican journalist was assassinated in Sinaloa, the drug capital of Mexico. According to Huffington Post, "Cárdenas began his career in journalism in the early 1990s, according to La Jornada, a Mexican news outlet where he worked as a national correspondent. He founded RioDoce in 2003, which has won several awards. He also won an International Press Freedom award in 2011.He compiled much of his reporting into several books, the most recent of which, Narcoperiodismo was published late last year. It tells the stories of Mexican journalists who have been victims of crimes." Javier Valdez Cárdenas presente! Today is World Press Freedom Day, declared by UNESCO as a way to bring attention to the critical role played by journalists in creating a just society. In recent months, we've seen the US press attacked by the Trump administration, a focus on "fake news," and other hostile characterizations of journalists that undermine the public's confidence in reporting. We can't lose sight, amid this anti-press propaganda, of how important journalism is to our freedom. A few days ago, I had the privilege to attend a lecture of Mexican journalist Anabel Hernandez, an investigative reporter whose recent book La Verdadera Noche de Iguala about the disappearance of 43 students in Guerrero has brought new attention to the horrendous crime. She lives in Berkeley now, having fled Mexico because of death threats. A few weeks ago, journalist Miroslava Breach was murdered outside her home while she was in her car with her children. The message left on a piece of cardboard said simply "tattle tale." Breach was well-known for reporting on the situation of the Raramuri in Chihuahua, an indigenous group who has been fighting narco-traffickers and illegal loggers. Many of them have been murdered as well. El Norte, a newspaper in Juarez, decided to close following her murder and the killings of two other journalists. Oscar A. Cantú Murguía, the newspaper's owner, said the closing was an act of protest. He told interviewers if there was no freedom of the press, he could do no more. Just yesterday the New York-based group Committee to Protect Journalists reported that Mexico is the most dangerous country for journalists where over 50 have been murdered since 2010. Gangs, cartels, and corrupt government officials have found is easy to silence criticism. The murders of journalists are rarely pursued. As a historian and as a fronteriza, the Mexican/ Spanish language press is important to me. Doing research about the early 20th century showed me that the Spanish language press was only the only medium that would cover issues related to Mexican Americans. Living on the border today has demonstrated the same. I know that newspapers like El Diario de El Paso will cover issues and events important to my community that English language newspapers will ignore. Anabel Hernandez courtesy of Journalists without Borders Anabel Hernandez and the widespread killing of Mexican journalists has shown me another reason to care about what happens to journalists in Mexico. Investigative reporters like Hernandez and the late Miroslava Breach risk their lives to reveal the corruption and power of drugs consumed in the United States. Without the US as a consumer of drugs like heroin, the cartels, the corrupt government officials and law enforcement officers would not have the money nor the motivation to kill these journalists. We are part of the problem. We are complicit. I read someone say once, "Each high an American experience is covered with the blood of the innocent." We are just getting a taste of what it is like to have our press constantly threatened and bullied by our government. We have to care about freedom of the press for ourselves and for our global neighbors. Today on World Press Freedom Day, I am honoring the journalists who have risked so much to uncover what Anabel Hernandez says is the truth that every victim and every society has the right to and which Miroslava Breach died for. Miroslava Breach courtesy of the BBC

In the 1990s, I taught at the University of Texas at San Antonio. One day after I had lectured about the Great Depression in Texas and mentioned the labor organizing of Emma Tenayuca, one student came up to me and said she was related to her. She went on to tell me that the family did not speak about her publicly because they were embarrassed by her activities so many decades earlier. It hurt my heart but I understood their hesitancy. She was a controversial woman in her time. Emma Tenayuca was a fierce defender of Mexican workers, especially women, and she spoke without hesitation about the terrible working conditions forced upon workers. Tenayuca was born in San Antonio in 1916 and as a child she accompanied her abuelito to La Plaza del Zacate to hear speakers talk about the ideals of the Mexican Revolution. She said those talks influenced her ideas of justice. Often women, especially the young and the old, have been excluded from our histories. Tenayuca is an example of the strong work of young women. At 16, she became involved in organizing cigar workers. By 21, she was an organizer with the National Workers' Alliance, which eventually brought together the Socialists and the Communists to work on behalf of workers who were suffering greatly during the economic crisis of the Great Depression.

She is most well-known for her work with the pecan shellers. If you have ever peeled pecans you know the fine powder that comes from the shell and that can irritate your skin. Imagine hundreds of women sitting in a room peeling pecans. The pecan dust filled the air. Their hands were reddened by the dust. In the 1930s it became cheaper for employers to hire Mexican American women at extremely low wages than to maintain pecan shelling machines. Pecan shellers were paid pennies and were offered all the pecans they could eat. When Tenayuca began organizing the workers for better pay and improved working conditions, 12,000 women walked off the job. After two months, employers gave in and raised their pay. This 1938 strike is often used as one of the examples of Mexican American women's power. While the success of the strike was a positive for Tenayuca, it also brought her more attention. When she prepared to give a speech at the city auditorium, a mob entered the building, ready to attack her. She was led out of the building to safety. That night, members of the mob joined the Ku Klux Klan in burning the mayor in effigy for defending her. Emma had joined the Communist Party in 1938 (and married Homer Brooks, the Chair of the Communist Party in Texas). Her affiliation with the CP lessened her effectiveness as a labor organizer and also resulted in her being blacklisted. She was unable to find work. During the Great Depression, the Communist Party gained the largest following it has ever had in the United States. Americans had been taught that if you work hard enough, you will make it. The Depression taught them that this was not true. Despite their hard work, many Americans were suffering from unemployment, homelessness, and hunger. In 1941, Emma and Homer divorced. In 1946, she left the Communist Party. She moved to the Bay area where she eventually became a school teacher. She returned to San Antonio in the 1960s and died in 1999. She has become a role model for many Mexican American women since because of her important labor organizing work and her fearlessness. In 2008, her niece Sharyll Tenayuca co-authored That's Not Fair! No Es Justo!: Emma Tenayuca's STruggle for Justice/La lucha de Emma Tenayuca por la justicia. I was happy to see this pride in her family about their brilliant relative. “I never thought in terms of fear. I thought in terms of justice,” she said. It is a lesson to us all. |

My father used to tell me about sneaking into this theater to watch movies as a kid in the 1910s. It showed Spanish language films. In the 1940s, it was transformed into a "whites only" theater but that didn't last long. By the 1950s, it was headquarters to the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers Union, a radical labor organization. Before it closed, it housed the Mine and Mill Bar.

Segundo Barrio

Father Rahm Street

July 2022

La Virgensita en la frontera

Cd Juarez downtown

December 2017

La Mariscal, Ciudad Juarez, 2017

Montana Vista 2019

El Centro July 2022